Jonathan Ruhe

Director of Foreign Policy

Ari Cicurel

Senior Policy Analyst

Acknowledgments

This report is made possible by the generous support of the Gettler Family Foundation. A portion of the re- search for this report was conducted on JINSA’s 2019 Benjamin Gettler International Policy Trip to Greece.

Executive Summary

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is shifting the geostrategic center of gravity in Europe eastward but also – due to the energy and logistics challenges it is creating – southward. This heightens the importance of a rapidly developing but underappreciated U.S. security partner: Greece. In particular, Greece offers the United States and its European allies a vital asset in the form of the port of Alexandroupolis on the northern Aegean. By- passing chokepoints controlled by an unreliable and often antagonistic Turkey, it offers unique opportunities for achieving shared transatlantic objectives to reduce Europe’s dangerous dependence on Russian energy; bolster the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) force posture in the increasingly contested Eastern Mediterranean, Balkans, and Black Sea; and ensure Ukraine’s prodigious food exports continue reaching markets in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

The United States and its allies must act with purpose to secure these goals, both in the near- and long-term.

On the energy front, Brussels’ deeply belated realization that it must cut loose from Moscow’s hydrocarbons is translating, first and foremost, into highly ambitious plans to diversify its sources of natural gas, including by finding ways to significantly increase imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) through southern Europe. Mean- while, Ankara’s willful abdication of its historical role as NATO’s southeastern bulwark, combined with serial underinvestment in defense by many of its European members, has left the alliance scrambling to ensure it can project growing numbers of forces into southeastern Europe, where both Russia and China are making serious inroads. At the same time, Moscow’s blockade of Ukrainian ports is raising risks of destabilizing food insecuri- ty – and with it, rising economic and political instability – in countries like Egypt, Lebanon, Libya, and Yemen.

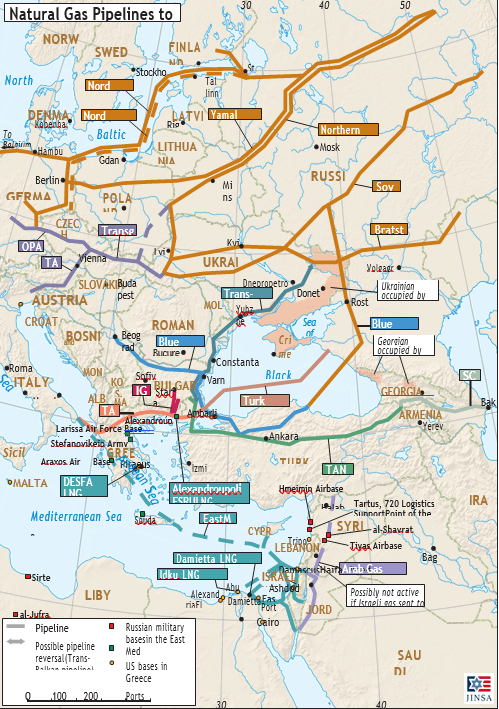

In all these respects, Alexandroupolis stands as a vital, if underappreciated and still untapped, strategic asset for the United States and Europe. As the European Union (EU) seeks to pivot from westbound Russian ener- gy deliveries toward those coming from the south, Alexandroupolis can significantly contribute to Greece’s ongoing efforts to become an energy import and distribution hub in southeastern Europe. The port is ideally situated at the nexus of the Mediterranean and a nascent lattice of natural gas pipelines spreading out through Italy and the Balkan countries, all of which have traditionally depended heavily on Russian energy (even by European standards).

In terms of defense, Alexandroupolis’ value is rising as NATO ramps up its rapid reaction force and its presence along the alliance’s sharpening frontlines in the Balkans, including Bulgaria and Romania. The Greek port avoids cumbersome bottlenecks in the heart of the continent that have long plagued plans to quickly move troops and equipment into southeastern Europe and sustain them there. By these same tokens, Alexandroupolis sits astride the most direct alternative southward corridor to the heavily mined Black Sea, whose access is controlled by Russia and Turkey, for getting Ukraine’s vital food exports to markets across the Mediterranean and Suez Canal.

American investments and other efforts to date, while certainly welcome, have yet to capitalize fully on the opportunities offered by Alexandroupolis. Though the United States backs the current construction of LNG import and pipeline distribution capacity in and around Alexandroupolis, more must be done in light of the heavy lifting still needed for Europe to effectively cut its Russian energy habit. The Biden administration’s January decision to drop support for a potential EastMed Pipeline (EMPL) has been at cross purposes with its own policy to reduce European dependence on Russian natural gas and U.S. partners’ larger concerted efforts to develop peacefully the region’s growing natural gas supplies and get them to European consumers.

Alexandroupolis already is enabling U.S. and other NATO forces to fly the flag and reassure allies throughout the Balkans and Black Sea littoral in response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, yet the port currently operates at a fraction of its potential capacity. And though the United States and Europe are actively seeking Ukrainian food export routes through northern Europe and Romania, the sheer scale of this challenge – combined with the need to move these supplies southward while avoiding the Black Sea as much as possible – makes Alex- androupolis a vital and logical, if currently underutilized, additional outlet.

Now, the United States and its NATO partners must do more to harness the opportunities offered by the port and by stronger defense cooperation with Greece more generally. The most pressing and impactful U.S. next steps should include:

Recommendation 1: Expand Alexandroupolis’ natural gas import and distribution capacity.

- Expand capacity of the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) pipeline from the currently constructed capacity of 3 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/yr) to 5 bcm/yr.

» In tandem, the United States and its allies should explore reversing the massive Trans-Balkan Pipeline to flow northward, thereby enabling LNG imports through Alexandroupolis to reach NATO members

Bulgaria and Romania, and possibly Moldova and Ukraine as well.

- Expedite the Trans Adriatic Pipeline’s (TAP) expansion from the current 10 bcm/yr to 20 bcm/yr.

- Beyond the floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) currently under construction at Alexandroupolis, back the development of additional Greek capacity to convert LNG to piped natural

Recommendation 2: Bolster U.S. support for European energy infrastructure.

- Increase the Biden administration’s June 2022 loan of $300 million to the Three Seas Initiative’s Invest- ment Fund (3SIIF) to speed the larger transformation of Europe’s energy infrastructure away from Russia and toward the

Recommendation 3: Support the peaceful development of Eastern Mediterranean energy.

- Appoint a S. Special Envoy for the Eastern Mediterranean to signal support for, and help concretely advance, EU efforts to increase natural gas imports from reliable U.S. partners in the Eastern Mediterra- nean—namely, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel.

Recommendation 4: Extend NATO’s Athens-Kavala fuel pipeline.

- Extend NATO’s existing Athens-Kavala fuel pipeline to Alexandroupolis, and from there into Bulgaria and Romania, in order to simplify logistics for the alliance’s power projection into the Eastern Balkans and Black Sea

Recommendation 5: Enhance Eastern Europe’s road and rail connections with Alexandroupolis.

- Increase financial and diplomatic leadership for 3SIIF and other initiatives to strengthen rail and road infrastructure extending outward from

Recommendation 6: Keep Alexandroupolis out of Russian hands.

- Provide diplomatic and economic assistance to ensure the privatization contract for Alexandroupolis port is awarded to an American company, in order to block Russian competitors from securing the contract and to signal S. commitment to counter the expansion of Russian and Chinese control over critical infrastructure across the broader region.

Recommendation 7: Deepen U.S. security cooperation with Greece.

- Capitalize on the Eastern Mediterranean’s vital geostrategic location, with Greece at its nexus, as a platform for projecting American and NATO power rapidly and more efficiently into Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa – including by harnessing Greece’s value as a site for combined and joint exercises that will be critical for helping meet NATO’s ambitious new goals to expand its high-readiness

Several of these steps to bolster European energy security and NATO force posture, including U.S. support for 3SIIF and ensuring the port privatization contract is awarded to an American company, will also contribute to Alexandroupolis becoming a key outlet for a north-south food export corridor from Ukraine.

Introduction

The U.S.-Greece defense partnership has grown steadily closer over the past decade, driven by sea changes in the Eastern Mediterranean and, more recently, Eastern Europe. The discovery of natural gas reserves off the shores of Cyprus and Israel, Turkey’s decreasing reliability as NATO’s southeastern anchor, and Moscow’s 2014 annex- ation of Crimea and invasion of Donbas contributed to Greece’s rising geostrategic importance. Now, Russia’s escalated aggression against Ukraine further increases the value of Greece as a security, energy, transportation, and logistics hub for the transatlantic alliance in the Balkans and Black Sea. Greece also is on the frontlines of China’s rising efforts to control ports and other critical infrastructure throughout the Eastern Mediterranean.

Greece’s geostrategic center of gravity is Alexandroupolis on the northern Aegean in the far northeast of the country. In 2021, Washington and Athens updated their bilateral Mutual Defense Cooperation Agreement (MDCA) to enhance deployments of U.S. forces and military equipment to and through the port there. The city and its environs boast a growing network of highways, as well as an airfield and basing facilities, to help

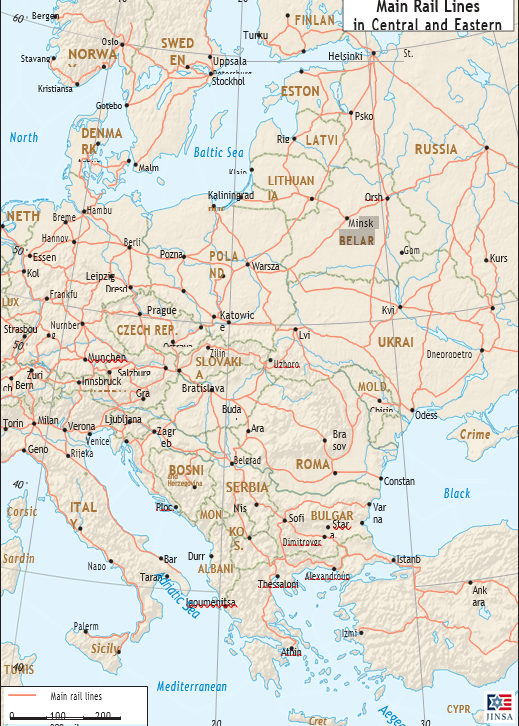

U.S and allied forces bypass the Turkish-controlled Bosporus and Russian-dominated Black Sea and more effectively project power into Bulgaria and Romania, all the way to the borders of Ukraine and Moldova. Ships docking at Alexandroupolis’ deep-water port can unload directly onto rail lines pushing upward through the Balkans as far north as Poland, further strengthening NATO’s ability to surge forces into Eastern Europe and creating commercial alternatives to the Chinese-run port of Piraeus farther south near Athens.

Since 2018, the United States also has helped build up Alexandroupolis as a key node for importing natural gas into the Balkans, thereby reducing Russia’s historical near-monopoly in this sphere. Reflecting Greece’s larger role as a growing energy import and distribution hub for Europe, the United States is supporting both the construction of a facility at Alexandroupolis to import liquefied natural gas (LNG), and the development of a network of pipelines to distribute it throughout southeastern Europe. Historically ground zero for ma- lign Russian influence in the country, Alexandroupolis now hums with American activity and symbolizes the growing U.S.-Greece partnership.

The strategic ceiling for Alexandroupolis is rising rapidly even higher amid Europe’s sudden but belated reali- zation that it must become energy independent from, and capable of defending its eastern marches against, Russia in the wake of the Ukraine invasion. Specifically, the continent’s longstanding imports of energy from the east now need to be replaced with those from the south, including the Eastern Mediterranean. At the same time, NATO urgently must address its limited ability to move forces eastward to shore up its increasingly con- tested front with Russia that stretches from Scandinavia and the Baltic down to the Eastern Mediterranean. Given Moscow’s blockade of the Black Sea, Europe also faces the challenge of ensuring Ukraine’s prodigious food exports reach their vulnerable markets to the south.

In all these respects, Alexandroupolis stands as a unique strategic asset. However, the United States and its NATO partners must do more to capitalize on the opportunities offered by the port and by stronger defense cooperation with Greece more generally.

Europe’s Reckoning

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has exposed crucial, if also long overlooked, weaknesses in European defense and energy security. Shared U.S. and EU objectives, which pre-date the current conflict, of reducing Europe’s vulnerability to Moscow’s energy leverage are now much more urgent than ever before. Serious effort will be required to replace the continent’s longstanding reliance on natural gas imports from the east with those from the south, including the Eastern Mediterranean. The transatlantic alliance likewise must look southward to resolve serious shortcomings in its current ability to move forces eastward and sustain them there, in order to deter further Russian aggression and reassure U.S. allies in southeastern Europe and the Black Sea littoral. Russia’s intentional disruption of Ukraine’s critical food exports further heightens the importance of infrastructure to connect Eastern Europe and outlets to the south.

A. Energy Pivot from Russia, Toward the South

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is setting in motion a momentous, and long overdue, European pivot away from its decades-old heavy dependence on Moscow for oil and especially natural gas. This has given Moscow ap- preciable and readily usable geopolitical leverage over the continent, and it continues to fill the Kremlin’s coffers for serial aggression. The ambitious scale and timeframe of the European Union’s (EU) energy goals point to the urgent need to develop significant infrastructure to bring supplies northward into the continent from the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere.

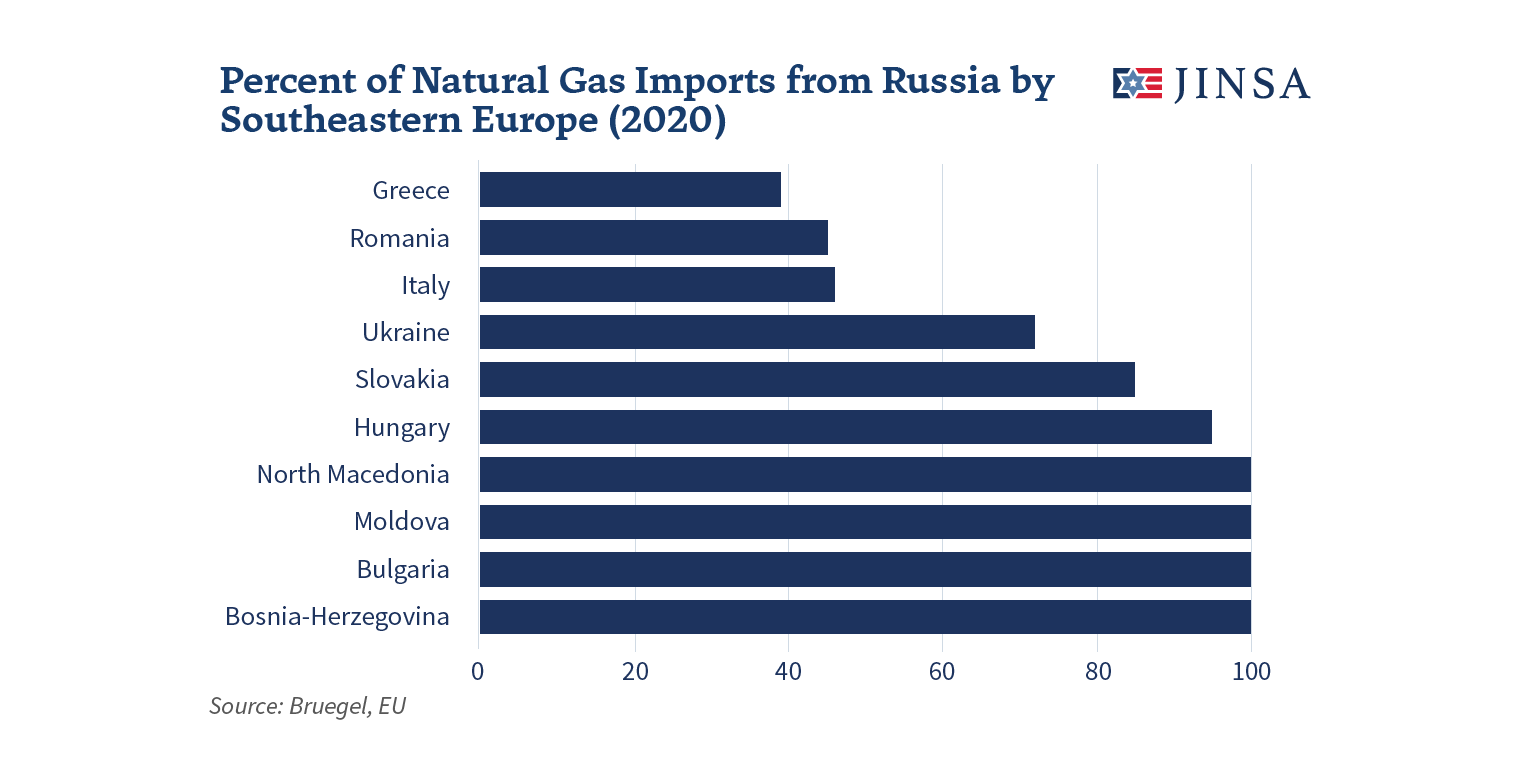

In March 2014 in Brussels, shortly after Russia’s illegal seizure of Crimea, then-President Obama told EU lead- ers how “this entire event has pointed toward the need for Europe to look into how it can diversify its energy sources” away from Russia.1 In 2018, then-President Trump warned the UN General Assembly that “reliance on a single foreign supplier can leave a nation vulnerable to extortion and intimidation.” Similar logic drove the Trump administration to support a proposed EastMed Pipeline (EMPL) that would deliver Cypriot and Israeli natural gas to Greece and Italy.2 In January 2022, the month before Russia invaded Ukraine, the Biden admin- istration abruptly ended U.S. support for EMPL on the stated basis of concerns about the project’s viability and the need to transition to more renewable energy sources.3 It did so despite a fairly clear-eyed intelligence picture of Moscow’s imminent intentions toward Kyiv, and despite the EU still depending on Russia for 40-45 percent of total natural gas consumption on the eve of the war.4 Southeastern Europe, in particular, relied on Russia for the vast majority of its natural gas at the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict.

Russian aggression is prompting an overdue about-face from Europe. Within weeks of Moscow’s invasion, Brussels quickly debuted plans to cut Russian imports by fully two-thirds in 2022 alone and achieve energy independence from Russia “well before 2030” – including by increasing natural gas imports via alternative pipelines and liquefied natural gas (LNG).5 To achieve these ambitious goals, Europe would need to develop new infrastructure to import and transport these supplies from, and via, the Eastern Mediterranean.

Percent of Natural Gas Imports from Russia by Southeastern Europe (2020)

Multiple factors appear set to magnify the challenges and urgency of Europe’s energy pivot. There is little, if any, existing excess capacity in natural gas pipelines that would provide the continent any significant available alternatives to Russia. Moreover, LNG terminals in the world’s three largest exporters – the United States, Aus-tralia, and Qatar – already are operating at full or near-capacity, and anyway Europe currently lacks sufficient terminals to import appreciable additional LNG.6

At the same time, and as it did during previous Ukraine tensions, Russia is again wielding its energy weapons. It has significantly reduced or completely ended natural gas shipments to nearly a dozen EU countries and could completely cut off parts of Europe in coming months. This is forcing the continent to revert to oil and coal power – forms of energy that produce appreciably more emissions than natural gas – to meet current energy demand, and to contemplate rationing natural gas and even shuttering power plants.7 In July, the Interna- tional Monetary Fund warned that, absent ramped up LNG imports, the lost economic output from Russian reductions in natural gas deliveries could exceed 2.5 percent of the entire EU’s gross domestic product (GDP).8

B. Can NATO Compete?

Vladimir Putin, and much of Russia with him, never internalized the Soviet Union’s defeat and dissolution at the end of the Cold War – an event he called “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.”9 Paired with a concerted remilitarization program, Russia under Putin began reasserting its influence and direct control over key stretches of the former Soviet Union and its client states, to the point where it once again is a credible great power competitor in Europe and the Mediterranean. Yet NATO has lagged dangerously behind not only Russia but also China, especially in southeastern Europe. In no small part, the alliance has been hobbled by the paucity of its logistical links to this increasingly militarized frontline.

Russia expands in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea

After its incursion into Georgia in 2008, Russia attacked Crimea and Donbas in 2014. In combination with its ongoing military modernization drive, this latter aggression led to Russian predominance in and around the Black Sea littoral, including by growing the size of its Sevastopol-based naval and air fleets and ringing the surrounding basin with sophisticated air and coastal defense systems such as the advanced S-300/-400.10 Moscow’s 2015 and 2020 interventions in Syria and Libya, respectively, extended this evolving Russian anti-ac- cess and area denial (A2/AD) envelope into the Eastern Mediterranean – an area in which NATO had enjoyed predominance throughout the Cold War.11 Combined with its soft annexation of Belarus in recent years,12 and now its full invasion of Ukraine, these aggressions have created a new Russian glacis that directly abuts NATO from the Baltics through the heart of Eastern Europe to the Black Sea’s western shores, and which even outflanks the alliance from the southeast in North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Turkey abdicates its NATO role

Russia’s remilitarization of NATO’s eastern front has occurred in parallel, and at times in tandem, with Turkey’s abdication under President Erdogan of its longstanding role as the alliance’s reliable southeastern bulwark. This includes Ankara’s continual threats to restrict military access to its bases by other alliance members, highly provocative procurement of Russian-made S-400 air defenses in 2017, and the steady ongoing uptick in its armed overflights of fellow NATO member Greece’s Aegean islands and threats to drill for energy in Greek territorial waters. Such actions have directly undermined transatlantic cohesion by triggering intra-alliance sanctions and even a mutual defense pact between two NATO members – France and Greece – against fellow ally Turkey.13 Tellingly, as Russia expanded its beachhead in Libya and bolstered its naval forces based in Syria in summer 2020, French and Turkish naval ships were preoccupied almost coming to blows in nearby Eastern Mediterranean waters.14

NATO’s eastern logistical challenge

While Putin was busy undoing the verdict of 1991, much of Europe saw it as something like the end of history. Along with the United States, the EU pursued a 1990s postwar “peace dividend” of reduced investment in military readiness. Only after the 2014 annexation of Crimea and invasion of Donbas did NATO agree, at least on paper, to sustain a high-readiness Response Force of 30,000 troops, with a stated goal of projecting power rapidly across Europe. It took two more years to begin implementing an Enhanced Forward Presence to counter Russia’s growing military presence in Eastern Europe, which amounted to four battalion-sized battlegroups – essentially tripwires of American, British, Canadian, and German troops – in Poland and the Baltics.15

China fills the gap

In parallel, the alliance and the EU failed to invest in infrastructure to support military logistics, leading to a dangerous set of port, rail, road, and maritime bottlenecks and other shortcomings that severely limit NATO’s ability to surge forces eastward. As former commander of U.S. Army Forces Europe Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges said in 2018, “after the wall came down … it didn’t even occur to anybody that we would have to be moving across Eastern Europe in any kind of military formation.”16

China wasted no time capitalizing on this lack of U.S. and NATO attention by filling some of Europe’s key infrastructural and logistical gaps. In particular, the Eastern Mediterranean’s historical importance as the crossroads of three continents, and as an anchor and gateway for southeastern Europe, is reflected in the priority granted it by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which seeks to expand China’s economic, technological, political – and ultimately military – influence and presence in Asian, African, and European trade arteries and other strategically vital nodes.

China scored a major foothold when Greece, with no competitive bids from American or European allies, sold majority control of its main port Piraeus in 2008 to the state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), a company with well-established ties to the People’s Liberation Army. Near Athens and the southeasternmost reaches of the European mainland, the port’s railheads provide much faster movement – and proliferation of Chinese influence – into the heart of the continent compared to a shipborne journey via Gibraltar, especially through areas critical for moving NATO forces eastward. Given recent funding proposals from Beijing’s state-af- filiated banks, these railways potentially will extend into NATO’s hardening frontlines in Eastern Europe as well. Notably this includes Hungary and Serbia, both of which enjoy openly warm relations with China and Russia.

By 2015, Chinese warships already had entered the Black Sea for the first time, shortly before exercising with their Russian counterparts in the Eastern Mediterranean; two years later, Chinese naval vessels called at Piraeus as well as ports in Israel and Turkey.17 During his 2019 visit to Athens President Xi even declared Piraeus the “dragon’s head” of China’s growing reach in the region.18 In this same period, COSCO and other state-affiliated Chinese companies acquired stakes in Israel’s main port of Haifa – prompting U.S. Navy threats to stop visiting the adjacent naval base – and in ports astride key Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea chokepoints like the Suez Canal and Bosporus.19 Tellingly, NATO’s Madrid Summit Declaration in June 2022 explicitly, and for the first time, named China as a “systemic competitor” who “challenges our interests, security, and values….”20

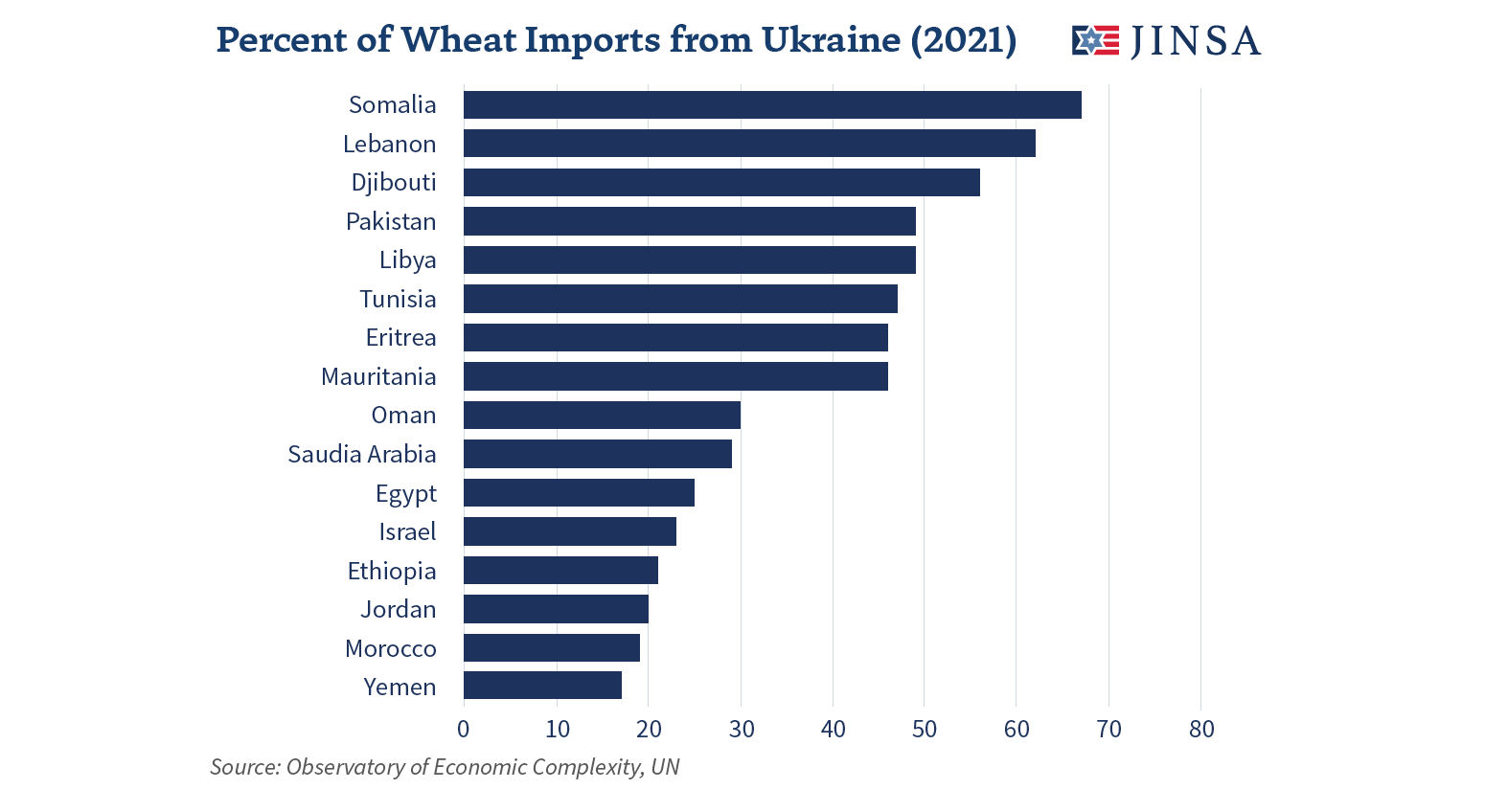

C. A Black Horse

For centuries Ukraine’s vast, rich belt of “black earth” has made it an agricultural breadbasket and, for that same reason, both a primary contributor to global food security and a prime target for conquest. Last year, the country exported more sunflower meal and oil than the rest of the world combined, and was among the world’s largest exporters of wheat, barley, corn, and rapeseed – almost all of which departed from Black Sea ports.

Russia’s invasion is systematically targeting Ukraine’s ability to sow, harvest, store, and export this prodigious grain and seed production. This includes blockading, bombing, or occupying most of Ukraine’s major food storage terminals and export hubs, outright stealing these resources, mining Black Sea shipping lanes, and simply rendering the country’s most fertile land untillable through massive months-long artillery assaults across Donbas. In June, Kyiv estimated it would export less than half of its reduced harvest this year – trans- lating to roughly a two-thirds reduction in food deliveries from the country compared to 2021 – and U.S. and EU officials predict Ukraine’s food exports will remain hampered for years to come.21 Even a July deal brokered by Turkey, which enabled Ukraine to resume limited seaborne food exports in August, remains tentative in light of Russia’s heavy mining of the Black Sea and continued targeting of Ukraine’s coast.22

Moscow’s intentional cutoff and theft of these resources already is exacerbating food prices and inflation globally. The effect will almost certainly be destabilization – including potentially famine – in food-insecure, and in many other ways already volatile, countries that depend heavily on Ukraine for grain, cooking oil, and other staples. The Eastern Mediterranean is particularly vulnerable, as Lebanon, Libya, and Tunisia counted on Ukraine to cover at least half their wheat imports; Egypt’s 100 million-plus population, as well as Jordan, import 20-25 percent of their wheat from Ukraine. South Asia, the Middle East, and the Horn of Africa also have sourced significant amounts of their basic food imports from Ukraine in recent years.23 Worsened by food insecurity, rising socioeconomic and political instability in these countries risks renewed mass migra- tions through the Eastern Mediterranean into Europe which, as with similar exoduses in recent years, would be exploited by Russia and other malign actors to ratchet up political tensions in the EU.

Percent of Wheat Imports from Ukraine

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity, UN

American and European Countermoves

The port of Alexandroupolis is critical for solving these energy security, defense, and food security challenges. However, given the scale and urgency of these problems, U.S. and European steps to date have been necessary but insufficient, particularly in terms of leveraging and expanding Alexandroupolis. As then-U.S. Ambassa- dor to Greece Geoffrey Pyatt said in April 2022, “certainly one of the consequences of this [Ukraine] war will be that the center of geopolitics of Europe is going to shift to the East and to the South.”24 In particular, not enough has been done to integrate the continent’s infrastructure with the Eastern Mediterranean and enable the more effective flow of energy and forces northward into Eastern Europe, and of food exports southward.

A. Energy Diversification

Even before Russia’s full-fledged invasion of Ukraine, the United States and EU undertook some initial steps to begin meeting Europe’s ambitious timelines for reducing its vulnerability to Moscow’s energy leverage, though more certainly is needed. In 2008 the EU executive proposed a “Southern Gas Corridor” to gradually replace westbound Russian imports with northbound Middle Eastern and Caspian supplies, including by building new pipelines. This initiative also began targeting Eastern Mediterranean supplies and LNG import capacity over the succeeding decade, as Cyprus, Egypt, and Israel discovered major offshore natural gas reserves and as LNG became increasingly viable.25

To this end, in 2016 EU-backed construction began on the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to link incoming Cas- pian natural gas, transshipped via Turkey, to Greece, Albania, and Italy. This was particularly important in the case of Italy, the EU’s second-largest consumer of natural gas, since it depended on Russia for 40 percent of its natural gas consumption on the eve of TAP’s operationalization in 2021.26 In 2018, Greece and the United States agreed to create an LNG terminal at Alexandroupolis to reduce the Balkans’ heavy reliance – even by European standards – on Russian energy, as well as on Turkey and the Bosporus.27

With U.S. support, and with EU funding secured in 2021, construction began in May 2022 on a Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) to enable LNG imports and convert them into gas at Alexandroupolis, which would then be pumped northward into a network of existing and proposed pipelines into the Balkans and TAP. As then-Ambassador Pyatt noted in May 2022, “as Europe is now moving rapidly to reduce its vulnerability to Russian energy blackmail and get away from Russian gas, the Alexandroupoli FSRU becomes more and more important.”28 One of these proposed pipelines, the U.S.-backed Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB), is set to move LNG imports through Alexandroupolis, as well as piped Caspian gas via Turkey, into Bulgaria.29 This is indispensable for Sofia, whose near-total dependence on Russian natural gas prior to Moscow’s April cutoff now gives it very real urgency to increase imports via Alexandroupolis.30 Furthermore, the FSRU will contribute to U.S. climate goals by enabling Balkan countries to reduce their reliance on more pollutive coal power plants.

Farther upstream, in June the EU finalized its first-ever energy deals with Israel and Egypt, which will expand Israel’s natural gas transit capacity to Egypt, at which point these supplies will be converted into rising LNG exports to European terminals.31 Last October, Greece and Egypt agreed for the latter to supply the former – and potentially Cyprus as well – with electricity via undersea cable, which could enable Athens to transship greater volumes of natural gas to Europe by reducing its consumption of imported fossil fuels, including from Russia, for power generation.32

These initial advances toward European energy diversification, while certainly welcome, also point to the work that lies ahead. Given the scale and urgency of the EU’s goals, much more will be needed from both the continent and U.S. leadership to make sustained advances on this score. The Biden administration justified its January decision to end U.S. support for the proposed EMPL on the grounds of lack of commercial viability, tensions with Turkey, and a shifting focus to “promoting clean energy technologies.”33 It did so despite the EU and Israel continuing to support the project, pending their final investment decision expected later this year, and despite the fact the pipeline would help significantly reduce southeastern Europe’s vulnerable dependence on Russian hydrocarbons. The decision also confirmed for Erdogan his country’s self-proclaimed role as the region’s primary energy transit hub, and thus further incentivizes Turkish bellicosity that directly threatens Greek, Cypriot, Israeli, and Egyptian projects to diversify European energy imports. Furthermore, as indicated by Europe’s recent reversion to far dirtier fuels like coal, dropping support for natural gas projects works at cross purposes to the stated goal of transitioning to clean energy. And, more generally, coming amid Europe’s monumental pivot in where and how its sources its energy, ending backing for the EMPL signals a lack of U.S. support for its partners’ concerted efforts to peacefully develop the Eastern Mediterranean’s natural resources and a lack of commitment to realizing European energy independence from Russia.

B. Bolstering NATO Force Posture

Since last year the United States and Europe have taken initial steps to enhance NATO’s power projection capabilities in Eastern Europe, though more is needed to enhance the alliance’s ability to push back against Russian and Chinese inroads by surging forces into the Balkans and ensuring force presence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

In October 2021, the United States and Greece extended and updated their bilateral Mutual Defense Cooper- ation Agreement (MDCA), which among other things stipulated jointly developing Alexandroupolis as part of a longer-standing U.S. and NATO objective – dating back to Russia’s seizure of Crimea – to move forces into the Eastern Balkans and Black Sea littoral. Even before Ankara closed the Turkish straits to military vessels in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Alexandroupolis’ large cargo pier, adjacent airport, links to adjoining road and rail networks, and military camp capable of hosting hundreds of U.S. troops made it a particularly attractive alternative to Turkey in terms of strengthening the alliance’s regional position, including rapidly reinforcing NATO members Bulgaria and Romania in the face of increasingly acute Russian threats.

Accordingly, Alexandroupolis is seeing enhanced U.S. and NATO presences since the MDCA’s update, begin- ning with increased deployments of U.S. forces and military equipment into Eastern Europe through the port late last year. These numbers grew following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when Alexandroupolis became a staging point for 3,000 NATO personnel to deploy into Bulgaria and Romania, as part the port’s broader contributions to an Eastern European force buildup by the alliance as far north as Poland.34 In March, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a U.S.-led carrier strike group conducted operations in the northern Aegean near Alexandroupolis.35

Since then, NATO announced the creation of new battlegroups in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia

– with the former three including American troops – and the United States said it would rotate forces through new bases being set up across Eastern Europe.36 Subsequently, the NATO summit in Madrid in June declared the alliance’s goal to expand its rapid response force from roughly 40,000 to more than 300,000 troops, in- cluding by upgrading their ability to move these forces around the continent more quickly and effectively.37

In light of the alliance’s challenges in surging forces eastward toward the Balkans from major bases in Central Europe, and of Turkey’s unreliable provision of access to the region, existing U.S. investment and presence at Alexandroupolis are crucial first steps toward helping meet NATO’s growing force posture requirements, particularly along the alliance’s vulnerable southeastern front. As Secretary of Defense Austin noted in July 2022, the port “has been instrumental in moving U.S. forces and equipment to and through NATO’s Eastern Flank.”38 He also noted that the priority access granted to the U.S. military there by Greece “allows us to con- tinue to provide military assistance to Ukraine and to counter malign actors and exercise and operate in the Balkans and eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea region.”39

But further U.S. and European engagement is needed. The port’s operations are set to be privatized, in order to enable greater throughput and efficiency at the currently underutilized pier as well as finance a potential additional pier and other upgrades – all of which could further enhance NATO’s ability to move and sustain forces in the Balkans. But American companies are vying against a Russian-aligned bidder for the port’s pri- vatization.40 Reflecting Alexandroupolis’ strategic location and infrastructure, as well as Russia’s historical influence in northern Greece, success by Moscow would enable a U.S. great power competitor to undermine or obstruct NATO’s expanding efforts to project power into an increasingly contested region stretching from

Ukraine and the Black Sea to the Aegean. In this light, in June 2022 the U.S. Ambassador to Greece, George Tsunis, emphasized the importance of “working to encourage American investments, especially in critical infrastructure sectors like shipbuilding and ports. That includes supporting the two American bidders we have for the port of Alexandroupolis.”41

C. Feeding the World

The United States and EU have struggled to develop reliable alternatives to the Russian-blockaded Black Sea for Ukraine’s critical food exports. Months of talks to resolve the crisis, including recent discussions facilitated by Turkey, have neither prevented foodstuffs from continuing to pile up in Ukrainian silos, nor prices from rising in Africa, Asia, and Europe.42 Given the sheer amounts of grain and other staples that need to be moved, discussions have focused on several overland alternatives, namely rail and river routes through Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Romania.43 Ukrainian President Zelensky’s June 2022 observation, that only a “much smaller volume can be supplied via new routes,” points to the need – even in the event of a secure corridor through Russia’s Black Sea blockade – for as many alternative and redundant pathways for Ukraine’s food exports as possible. The importance of outlets in southern Europe is particularly acute, since Kyiv’s harvests historically headed south to the Eastern Mediterranean and, via the Suez Canal, Africa and Asia.44 Alexan- droupolis already has proven its ability to serve as an export terminal for grain harvested from northeastern Greece, without interfering with military traffic at the port.

Recommendations

The shared U.S. and European need to reorient much of the continent’s infrastructure points to Alexandroupolis as a ready solution, both immediately and as an increasingly utilizable asset over the longer term. The port’s vital strategic location and growing infrastructure connecting the Eastern Mediterranean with southeastern Europe and the Black Sea makes it an ideal location for greater U.S. cooperation with its regional partners to bolster EU energy security, NATO defenses, and global food security.

A. Energy Security

The United States should take a series of steps to support Alexandroupolis’ growth as a vital component in Greece’s broader project to become an energy import and distribution hub for Europe’s pivot away from Russian hydrocarbons.

Recommendation 1: Expand Alexandroupolis’ natural gas import and distribution capacity.

The United States should begin proactively exploring options to expand the IGB pipeline from its currently constructed capacity of 3 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/yr) to 5 bcm/yr. In turn, this could help boost the viability of reversing the massive Trans-Balkan Pipeline, which was designed initially to flow southward from Ukraine into the Eastern Balkans. Together, U.S. support for these projects could enable natural gas from Greece to replace lost Russian supplies not only to NATO members Bulgaria and Romania, but even to Moldova and Ukraine.

Similarly, given Italy’s strong dependence on Russian energy imports, the United States should consider options to promote the early doubling of the TAP pipeline’s capacity from the current 10 bcm/yr to 20 bcm/ yr. Given the EU’s stated goals of expanding LNG import capacity to reduce Russian natural gas deliveries, the United States also should build on its existing backing for the Alexandroupolis FSRU by supporting even greater capacity in Greece to convert LNG to piped natural gas.

Recommendation 2: Bolster U.S. support for European energy infrastructure.

Recent steps by the Biden administration to back the Three Seas Initiative, in the form of a $300 million loan in June 2022 for energy projects directed by the Initiative’s Investment Fund (3SIIF), are necessary but insuf- ficient financial support for a larger transformation in Eastern and Central Europe away from Cold War-era transportation and energy infrastructure that mostly runs east-west – connecting Russia with its former Soviet republics and Warsaw Pact satellites – to the construction of south-north corridors linking the region to new non-Russian energy transit points in Greece and possibly other key nodes in southern Europe.

Recommendation 3: Support the peaceful development of Eastern Mediterranean energy.

Washington should wholeheartedly support the EU’s growing efforts to grow its energy imports from reliable

U.S. partners around the Eastern Mediterranean basin, namely Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel. Given Tur- key’s counterproductive interference with these countries’ peaceful energy exploration, the United States will need to assert a clear and long-overdue leadership role in the region, first by explicitly supporting natural gas development as a critical piece of Europe’s energy security – a “bridge” – to enable reduced reliance on Russia and a longer-term transition to more renewable energy sources. Most immediately, the Biden administration should reverse its misguided decision to drop support for the EMPL and explicitly support the EU, Israel, and Egypt as they make their own financial and technical decisions about future projects to develop and deliver Eastern Mediterranean natural resources to Europe. The administration also should appoint a Special Envoy for the Eastern Mediterranean. S/he could reinforce and help direct these efforts by enhancing U.S. partici- pation in regional fora like the Greco-Cypriot diplomatic, economic, and security “trilaterals” with Israel and Egypt, as well as the East Mediterranean Gas Forum.

B. Strengthening NATO

The United States also should support further development of Alexandroupolis as a crucial hub, with a high ceiling, in NATO’s revived, long-term continental confrontation with Russia and its growing great power com- petition with China.

Recommendation 4: Extend NATO’s Athens-Kavala fuel pipeline.

The United States should work with its allies to extend NATO’s existing Athens-Kavala fuel pipeline to Alex- androupolis. Extending the pipeline and associated fuel storage capacity would support more rapid and sustained use by U.S. and allied forces of rail, road, and air assets in and around northeastern Greece. This in turn would enhance NATO power projection into the Eastern Balkans by facilitating a further extension of the pipeline to Bulgaria and Romania, the route to which is easier and cheaper to construct from Alexandroupolis than from the existing terminus at Kavala.

Recommendation 5: Enhance Eastern Europe’s road and rail connections with Alexandroupolis.

Building on what it has begun regarding energy projects, and given the paucity of adequate rail and road infrastructure in the Eastern Balkans, the Biden administration also should extend financial support for 3SIIF and other initiatives to reorient southeastern Europe’s transportation networks away from Russia and enhance its connections with the existing road and rail infrastructure extending northward from Alexandroupolis. A clear U.S. commitment to strengthening NATO infrastructure here also will go a long way to shouldering out competing Chinese and Russian investment in this increasingly strategic region.

Recommendation 6: Keep Alexandroupolis out of Russian hands.

Such steps point to the more fundamental need for the United States to show up in the Eastern Mediterranean, a region from which it has often been absent since the end of the Cold War, even amid significant energy dis- coveries and rising security competition driven by Turkey, Russia, and China. Most immediately, this means ensuring an American company is successful in the zero-sum competition against Russian-aligned attempts control the future development of Alexandroupolis port. To strengthen U.S. involvement and support for critical infrastructure projects in Greece, Ambassador Tsunis has noted the important roles to be played by

U.S. government agencies including the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and Export-Import Bank of the United States.45

Recommendation 7: Deepen U.S. security cooperation with Greece.

More generally, the United States should take advantage of the Eastern Mediterranean’s vital geostrategic location, with Greece at its nexus, as a platform for projecting American and NATO power rapidly and more efficiently into Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. This includes Greece’s value as a site for combined and joint exercises that will be critical for helping meet NATO’s ambitious new goals to expand its high-read- iness forces in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

C. Ensuring Food Security

Several of these steps to bolster European energy security and NATO force posture, including U.S. support for 3SIIF and ensuring the port privatization contract is awarded to an American company, also will contribute to Alexandroupolis becoming a key outlet for a north-south food export corridor from Ukraine.

Endnotes

- Dave Keating, “Obama urges EU to diversify its energy sources to end dependency on Russia,” Politico, March 26, 2014, https://www.politico.eu/article/obama-urges-eu-to-diversify-its-energy-sources-to-end-dependen- cy-on-russia/.

- Philip Chrysopoulos, “How the US Helped Bring About EastMed Pipeline Deal,” Greek Reporter, January 3, 2020, https://greekreporter.com/2020/01/03/how-the-us-helped-bring-about-eastmed-pipeline-deal/.

- “U.S. State Department Withdraws Support of EastMed Natural Gas Pipeline,” Keep Talking Greece, January 9, 2022, https://www.keeptalkinggreece.com/2022/01/09/eastmed-usa-withdraw-support/.

- “How Europe can cut natural gas imports from Russia significantly within a year,” International Energy Agency, March 3, 2022, https://www.iea.org/news/how-europe-can-cut-natural-gas-imports-from-russia-significantly- within-a-year.

- Mark Thompson, “Europe plans to slash Russian gas imports by 66% this year,” CNN, March 8, 2022, https:// cnn.com/2022/03/08/energy/gas-russia-europe/index.html; “A 10-Point Plan to reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas, International Energy Agency,” March 2022, https://www.iea.org/re- ports/a-10-point-plan-to-reduce-the-european-unions-reliance-on-russian-natural-gas.

- Drew Hinshaw, Laurence Norman, and Bojan Pancevski, “As Russia Threatens Ukraine, Europe Scrambled to Secure Gas Supply,” The Wall Street Journal, January 27, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-standoff- prompts-europe-to-enlist-u-s-help-securing-gas-11643294410.

- Loveday Morris, Sammy Westfall, and Reis Thebault, “Russia’s chokehold over gas could send Europe back to coal,” The Washington Post, June 22, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/06/22/coal- plant-europe-germany-austria-netherlands-russia-gas/; Melissa Eddy, “Germany will fire up coal plants again in an effort to save natural gas,” The New York Times, June 19, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/19/ world/europe/germany-russia-gas.html; Christina Lu, “Europe’s Worst Energy Nightmare Is Becoming Reality,” Foreign Policy, July 11, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/11/europe-energy-crisis-natu-

ral-gas-russia-nord-stream-1/; Emily Rauhala et al, “Russia cuts off gas to Poland, Bulgaria, stoking tensions with E.U.,” The Washington Post, April 26, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/26/rus- sia-cuts-gas-bulgaria-poland-gazprom/; Adam Taylor, Loveday Morris, and Kate Brady, “Russia’s gas cuts to

Europe in summer could bring a bitter winter,” The Washington Post, June 17, 2022, https://www.washington- post.com/world/2022/06/17/russia-gas-gazprom-nordstream/.

- Jason Douglas and Laurence Norman, “Vital Russian Gas Supplies to Europe Aren’t Expected to Restart, Says European Commission,” The Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/arti- cles/2022-07-19/european-commission-doesn-t-expect-russia-to-restart-nord-stream.

- “Putin: Soviet collapse a ‘genuine tragedy’,” NBC News, April 25, 2005, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/ wbna7632057.

- Michael Peterson, “The Naval Power Shift in the Black Sea,” War on the Rocks, January 9, 2019, https://waron- com/2019/01/the-naval-power-shift-in-the-black-sea/.

- Eastern Mediterranean Policy Project, At the Center of Crossroads: A New U.S. Strategy for the East Med, Jewish Institute for the National Security of America, November 11, 2021, https://jinsa.org/jinsa_report/at-the-cen- ter-of-the-crossroads-a-new-u-s-strategy-for-the-east-med/.

- Yasmeen Serhan, “The Russian Incursion No One is Talking About,” The Atlantic, February 22, 2022, https:// theatlantic.com/international/archive/2022/02/russia-creeping-annexation-belarus/622878/

- John Psaropoulos, “Greece ratifies landmark intra-NATO defence pact with France,” Al Jazeera, October 7, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/7/greece-ratifies-intra-nato-defence-pact-with-france.

- John Irish and Robin Emmott, “France-Turkey tensions mount after NATO naval incident,” Reuters, July 7, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-france-turkey-analysis/france-turkey-tensions-mount-after-na- to-naval-incident-idUSKBN2481K5.

- “NATO rapid response force to expand to 30,000 troops,” The Lithuania Tribune, February 5, 2015, https://lithu- com/nato-rapid-response-force-to-expand-to-30000-troops/.

- Michael Peel and Michael Acton, “Red tape, radios and railway gauges: Nato’s battle to deter Russia,” Financial Times, January 2, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/90345ab8-dff5-11e7-a8a4-0a1e63a52f9c; Hanne Coke- laere and Joshua Posaner, “Europe’s roads and railways aren’t fit for a fight with Russia,” Politico, April 8, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-military-mobility-budget-slammed-as-almost-nothing-to-tackle-rus- sia-challenge/.

- Sam LaGrone, “Two Chinese Warships Enter Black Sea, Reports Link Visit to Possible Chinese Frigate Sale to Russia,” USNI News, May 5, 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/05/05/two-chinese-warships-enter-black-sea-re- ports-link-visit-to-possible-chinese-frigate-sale-to-russia.

- “Xi eyes deeper cooperation on occasion of visit to Greece,” Kathimerini, November 10, 2019, https://www. com/news/246317/xi-eyes-deeper-cooperation-on-occasion-of-visit-to-greece/.

- David Shinn, China’s Maritime Silk Road and Security in the Red Sea Region, Middle East Institute, May 18, 2021, https://www.mei.edu/publications/chinas-maritime-silk-road-and-security-red-sea-region.

- “Madrid Summit Declaration,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, June 29, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/ en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm.

- Patrick Tucker, “Russia Is Boosting Food Prices to Undermine Global Support for Sanctions, Officials Say,” De- fense One, June 4, 2022, https://www.defenseone.com/technology/2022/06/russia-boosting-food-prices-un- dermine-global-support-sanctions-officials-say/368504/; Alistair MacDonald and Thomas Grove, “Ukraine’s Farmers Start Harvest With Few Places to Store Grain,” The Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2022, https://www. com/articles/ukraines-farmers-start-harvest-with-few-places-to-store-grain-11655636400; Vivian Salama and Bojan Pancevski, “World Leaders Seek Solutions to Food Shortages Caused by Ukraine War,” The Wall Street Journal, June 24, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/world-leaders-seek-solutions-to-food-shortages- caused-by-ukraine-war-11656078747.

- Elvan Kivilchim and Jared Maslin, “Turkey Launches Monitoring Site for Ukraine-Russia Grain Deal,” The Wall Street Journal, July 27, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/turkey-launches-monitoring-site-for-ukraine-rus- sia-grain-deal-11658925605.

- Kali Robinson, “How Russia’s War in Ukraine Could Amplify Food Insecurity in the Mideast,” Council on For- eign Relations, April 21, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/how-russias-war-ukraine-could-amplify-food-inse- curity-mideast.

- “Ambassador Pyatt’s Farewell Interview with Tom Ellis, Editor in Chief, Kathimerini English Edition,” U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Greece, April 30, 2022, https://gr.usembassy.gov/ambassador-pyatts-farewell-inter- view-with-tom-ellis-editor-in-chief-kathimerini-english-edition/.

- “Diversification of gas supply sources and routes,” European Commission, https://energy.ec.europa.eu/top- ics/energy-security/diversification-gas-supply-sources-and-routes_en.

- “Italy’s dependence on Russian gas down to 25% from 40%, Draghi says,” Reuters, June 24, 2022, https:// reuters.com/business/energy/italys-dependence-russian-gas-down-25-40-draghi-says-2022-06-24/.

- Nick Kampouris, “Greece’s Gas Company Signs Major Deal for Alexandroupolis’ Terminal,” Greek Reporter, September 7, 2018, https://greekreporter.com/2018/09/07/greeces-gas-company-signs-major-deal-for-alex- androupolis-terminal-photos/.

- Constantine Atlamazoglou, “US Marines and Sailors Ate All the Food in Greek Port Alexandroupoli, Business Insider, August 3, 2022, https://www.businessinsider.com/marines-sailors-ate-all-the-food-in-greek-port-alex- androupoli-2022-8.

- Steven Tagle, “As war in Ukraine intensifies, Greece promotes Balkan energy security,” Institute of Current World Affairs, June 30, 2022, https://www.icwa.org/greece-promotes-balkan-energy/.

- Derek Gatopoulos, “New gas pipeline boosts Europe’s bid to ease Russian supply,” Associated Press, April 29, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-covid-health-business-germany-274aae7fd9dfa88bab1dd26 200db9423.

- Jonathan Ruhe and Samuel Millner, “U.S. Leadership Needed on East Med Energy,” Jewish Institute for the National Security of America, June 21, 2022, https://jinsa.org/jinsa_report/us-leadership-needed-on-east- med-energy/.

- Paul Tugwell and Georgios Georgiou, “Egypt Set to Agree on Electricity Link-Up With Greece,” Bloomberg, October 13, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-13/egypt-set-to-agree-on-electricity- link-up-with-greece?sref=m52Hjoet.

- Jonathan Ruhe and Sam Millner, “U.S. Must Support East Med Energy Security,” Jewish Institute for the National Security of America, March 16, 2022, https://jinsa.org/jinsa_report/us-must-support-east-med-ener- gy-security/.

- Vassilis Nedos, “Greek role within NATO is upgraded,” Kathimerini, March 14, 2022, https://www.ekathimerini. com/news/1179620/greek-role-within-nato-is-upgraded/.

- “Truman Operates in North Aegean Sea,” S. Navy, March 7, 2022, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/ News-Stories/Article/2958122/truman-operates-in-north-aegean-sea/.

- “NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, July 8, 2022, https:// nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_136388.htm.

- Lili Bayer and Hans Von Der Burchard, “NATO pledges 300K troops, then leaves everyone guessing,” Politico, June 28, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/jens-stoltenberg-madrid-nato-summit-pledges-300k-troops- then-leaves-everyone-guessing/.

- “Readout of Secretary of Defense Llyod Austin III’s Meeting With Greek Minister of Defense Nikos Panag- iotopoulos,” U.S. Department of Defense, July 18, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/ Article/3097006/readout-of-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iiis-meeting-with-greek-minister/.

- Todd Lopez, “Strategic Port Access Aids Support to Ukraine, Austin tells Greek Defense Minister,” U.S. Department of Defense, July 18, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3097081/ strategic-port-access-aids-support-to-ukraine-austin-tells-greek-defense-minist/.

- “Alexandroupolis: a new energy and transportation hub for Greece,” Greek City Times, March 31, 2022, https:// com/2022/03/31/alexandroupolis-a-new-energy-and-transportation-hub-for-greece/.

- Lena Argyri, “US-Greek relationship makes EU ‘more secure’,” Kathimerini, June 19, 2022, https://www.ekathi- com/opinion/interviews/1187104/us-greek-relationship-makes-eu-more-secure/

- Beril Akman, Megan Durisin, and Daryna Krasnolutska, “Ukraine Grain Talks With Russia Take Step For- ward,” Bloomberg, July 13, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-13/turkey-says-ini- tial-steps-made-toward-unblocking-ukraine-grain?sref=m52Hjoet.

- Jared Malsin, Alistair MacDonald, and Stephen Kalin, “Russia, Ukraine, and Turkey Approach a Deal on Ukraine Grain Exports, Officials Say,” The Wall Street Journal, July 13, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ ukraine-russia-turkey-and-u-n-hold-talks-on-exporting-grain-blockaded-by-war-11657721132.

- Elisabeth Braw, “The Danube Won’t Solve Ukraine’s Grain Problems,” Defense One, July 15, 2022, https://www. com/ideas/2022/07/danube-wont-solve-ukraines-grain-problems/374508/.

- Lena Argyri, “US-Greek relationship makes EU ‘more secure’,” Kathimerini, June 19, 2022, https://www.ekathi- com/opinion/interviews/1187104/us-greek-relationship-makes-eu-more-secure/