Thoughts in and around geopolitics.

I have to confess that I find it difficult to hold an analytic distance on Afghanistan. I am angry – at no one in particular – that more attention has been paid to the last few days of this war than to the decades and indeed all the casualties that came before it. The deaths piled up over years, the war went nowhere, and the Americans over time lost interest. It’s as if the last 40 years of the U.S. war in Afghanistan never merited much public attention or judgment, and now there is an obsession with its final days.

That’s not a typo. Most think of this as a 20-year war. But in fact it was twice as long, involving ruthlessness and courage on all sides. To me, it began in December 1979, when I was 30 years old – which is how long ago it was. The Soviet Union invaded over a concern about which faction would govern Afghanistan. At that point, Central Asia was still part of the Soviet Union, so the Soviet Union shared a border with Afghanistan. Put simply, it wanted another satellite on its border.

The invasion took place right after Iran seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took the diplomats hostage. The U.S. was obsessed with Iran and the Persian Gulf. The Arab oil embargo was still haunting the American economy, and President Jimmy Carter was extremely sensitive to a country blocking the Gulf and affecting the coming election. It was hard to understand why the Soviets sent conventional forces into Afghanistan to control politics. The Soviets had massive covert assets in country to manage it. Unable to understand Soviet reasoning or actions, many theories emerged, each flawed in some way. One was that the invasion of Afghanistan was the first step in a move into Iran to support the communist Tudeh Party as it tried to acquire more power. The theory really didn’t fit, but it was the most frightening so it had the most weight. The United States had to act.

Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, was also extremely concerned about Soviet intentions. Some time earlier, the Grand Mosque in Mecca had been seized by insurgents and was eventually displaced by Saudi and Pakistani troops. There were various claims that the takeover had been underwritten by the Soviets. The Saudis likely didn’t believe this, but their nerves were frayed anyway thanks to Soviet support for Syria, Iraq and Egypt – secular regimes hostile to the Saudis. The Saudis were extremely sensitive to the Soviets’ move in Afghanistan. Pakistan was even more so.

The United States had no reasonable military option. It crafted another strategy: to support an insurgency in Afghanistan against the Soviets. Some saw it as payback for Vietnam. The problem was how to generate such a rising. Operation Cyclone, as it was known, was conceived of in three parts. The Saudis would recruit and deploy motivated jihadists to Afghanistan to raise indigenous forces and lead the struggle against the Soviets. The Saudis would also fund the operation. Pakistan’s intelligence agency would provide training facilities and instructors. The United States would oversee the operation, aid in the training and provide intelligence to the fighters.

Started under Carter but kicked into high gear after Ronald Reagan succeeded him, Operation Cyclone had a substantial budget that was able to provide the rebels with sophisticated weapons such as mines, anti-tank and anti-air systems, and communication systems. The degree to which U.S. intelligence and special operations forces were on the ground in Afghanistan is not entirely clear. It would be speculative to assume that training took place in Afghanistan, rather than shuttling people into Pakistan, and might have required U.S. trainers or inspection to judge performance.

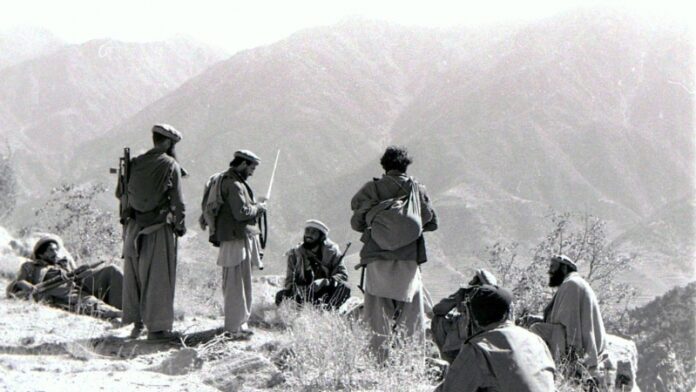

The three nations were in effect training Islamist fundamentalists to enter Afghanistan and raise an army of mujahedeen insurgents less to control Afghanistan than to bleed the Soviets. The operation succeeded. On Feb. 15, 1989, the commander of Soviet forces and the last to leave Afghanistan turned and spat on the last piece of Afghan territory he stood on. The Russians had been exhausted by an aggressive force reasonably well armed and extremely motivated.

The Afghan fiasco was one of the factors that toppled the Soviet Union two years later. The decision to go into Afghanistan, and remain there for more than 10 years while losing men to what had first appeared to be a ragtag force of religious fanatics, weakened an already creaking regime. It is not fair to say that the U.S., Pakistan and Saudis created this force. The Afghans had been eager to fight, needing only to be given weapons and training. In retrospect, this is the story of all great powers that tried to subdue Afghanistan.

Of course, there were those who argued that the Soviets could not possibly reach the Persian Gulf through Afghanistan. There were also those who warned that the mujahedeen would have neither loyalty to nor gratitude for their three patrons. They would be aware they were being used and, once empowered, use it as an opportunity to build an Islamist Afghanistan. But the American hypersensitivity to Soviet moves, coupled with a lack of understanding of either Afghanistan or the type of Muslim wishing to fight in Afghanistan, meant that the Americans didn’t grasp what it meant to be a jihadist. In the end, some of them returned to Saudi Arabia, and others remained in Afghanistan because Saudi Arabia, which understood who these fighters were, wouldn’t let them in.

Washington never understood what it had created, and some of the popular culture of the time reflects as much. “Rambo III” was released in 1988. It showed famed veteran John Rambo, who was recruited by American operatives, entering Afghanistan and joining a mujahedeen force. In one scene, a youngster is shown downing a Soviet helicopter with a MANPAD. The kid’s joy warmed Rambo’s heart. The movie may or may not have had technical advisers who may or may not have been familiar with Afghanistan, but either way the depiction of Rambo’s relationship to jihadists was astonishing then, even more so now.

The U.S. scaled down Operation Cyclone and eventually lost interest in Afghanistan. This was the time when a civil war between various factions broke out, and the Taliban emerged as the government. But Cyclone lived on at least in spirit. After 9/11, whose anniversary we will observe next week, the U.S. sent operatives into Afghanistan to contact former allies and recruit them to locate and capture Osama bin Laden. Old friends fought together again, and the Afghans seemed to have found bin Laden, but he slipped away into Pakistan all the same. Our allies took the money that was delivered to them but, alas, weren’t successful in their mission. And so a raid to get bin Laden turned into a war whose end was unknown.

In 1989, the U.S. obsession was the Soviet Union. It was a reasonable thing to be obsessed with. Washington responded to every move it made, and vice-versa. The ability to imagine how the stinger missiles would lead to the disastrous withdrawal just experienced could not be reasonably expected. But there were points at which we could see what we had done, long after the beginning. That is hindsight. This war was launched by Carter and continued in some form or another until now. And for the American people, it was rarely thought of, and the price rarely considered, a war of 40 years, a war of death and mayhem. It was a sideshow for those of us who demand accountability, yet rarely hold ourselves accountable.

And for this reason I am angry at the anger of the past few weeks. Where were we for the past four decades? The war was not a secret, nor were its dangers and probable outcome unknown. I mourn all those killed and those who are now unable to leave Afghanistan. But the casualties of the end were a very small fraction of the casualties incurred over the decades on all sides. At some point, democracy demands that the people hold themselves accountable rather than merely those they elect. Democracy is not simply about rights. It is also about responsibility and, in this case, a 40-year war dragging on in its murderous way. I did not stir myself to speak out. I will not condemn my fellow citizens or my government for what I myself failed to do.