The Washington Post

The Washington Post

Retired Marine Gen. James N. Mattis was confirmed and sworn in as President Trump’s defense secretary Friday, breaking with decades of precedent as a recently retired general became the Pentagon’s top civilian leader.

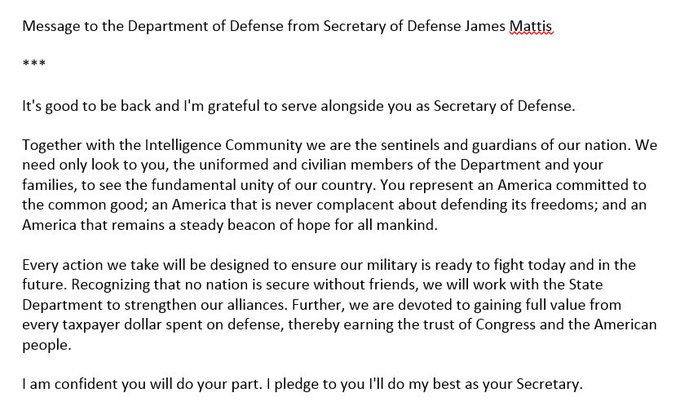

Mattis, 66, was approved with a 98-1 vote after the presidential inauguration and then sworn in by Vice President Pence. The new Pentagon chief released a statement to U.S. troops afterward that credited not only them, but intelligence personnel as “sentinels and guardians of our nation” — rhetoric that is in line with Mattis’s past statements, but stands in contrast to the way Trump has criticized the value of U.S. intelligence in recent weeks.

Mattis also pledged to work with the State Department to strengthen U.S. alliances abroad, some of which have been rattled by Trump questioning their worth.

“We need only look to you, the uniformed and civilian members of the Department and your families, to see the fundamental unity of our country,” Mattis’s statement said. “You represent an America committed to the common good; an America that is never complacent about defending its freedoms; and an America that remains a steady beacon of hope for all mankind.”

[Mattis isn’t just a popular general anymore. He’s an icon faced with running the entire Pentagon.]

Many lawmakers and long-time foreign policy observers hope Mattis can be a moderating voice of experience in an administration that has notably few senior officials with national security experience in Washington. He will lead the Defense Department’s 1.9 million active-duty service members and reservists and oversee a budget of more than $580 billion as Trump prepares to expand the military.

Mattis becomes the first senior military officer to serve as defense secretary since President Truman nominated Army Gen. George C. Marshall for the job in 1950, as the U.S. military struggled in the Korean War. Mattis retired in spring 2013 as the chief of U.S. Central Command after a career in which he became one of the most influential officers of his generation and commanded troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The @vp has sworn in James Mattis as the Secretary of Defense #Inauguration

In his Jan. 12 confirmation hearing, Mattis said he never anticipated he would be nominated for the job and was “enjoying a full life west of the Rockies” when Trump asked to meet with him.

“I was not involved in the presidential campaign, and I was certainly not seeking or envisioning a position in any new administration,” Mattis said. “That said, it would be the highest honor if I am confirmed to lead those who volunteer to support and defend the constitution and to defend our people.”

Here’s Defense Secretary James Mattis’s first public comments in his new job. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2017/01/20/senate-confirms-retired-gen-james-mattis-as-defense-secretary-breaking-with-decades-of-precedent/?utm_term=.6b72101ce3d9 …

To allow Mattis to become defense secretary, Congress passed legislation to overcome a law first passed in 1947 that banned recent veterans from the position. For decades, there was a 10-year moratorium; it was reduced to seven years in 2008. The waiver for Mattis passed 81-17 in the Senate, and then 268 to 151 in the House.

[How Trump picking Mattis as Pentagon chief breaks with 65 years of U.S. history]

Mattis broke with Trump’s past rhetoric in several instances during his confirmation hearing, arguing that there are few places where Washington is likely to find common ground with Russia and that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance is vital. Trump has sought closer ties with Russia, and called NATO obsolete.

“History is not a straitjacket, but I’ve never found a better guide for the way ahead than studying the histories,” Mattis said. “We have a long list of times we’ve tried to engage positively with Russia. We have a relatively short list of successes in that regard.”

But Mattis expressed common ground on other issues, including a belief that the U.S. military needs to be fortified.

Defense Secretary James Mattis smiles as he testifies during his confirmation hearing Jan. 12, 2017, before the Senate Armed Services Committee. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

“Bottom line, you get to a point where you have the fewest big regrets when the crisis strikes,” Mattis said. “You will never have no regrets because we’re dealing with something that is fundamentally unpredictable.”

Mattis will be joined in the Pentagon by two other Marines in senior positions: Gen. Joseph F. Dunford, who is chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Deputy Defense Secretary Robert O. Work. Work served in the Obama administration, but has agreed to stay on for several months to provide continuity.

[Here are the people Donald Trump has chosen for his Cabinet]

Officials working for Trump still haven’t announced nominees for several other senior positions, including Air Force secretary, Navy secretary and undersecretary for policy. Outgoing Pentagon Press Secretary Peter Cook said Thursday that the many service members in the Pentagon will help make the transition to the Trump administration a success.

“The continuity that is here and the experience within the Department of Defense is significant,” Cook said. “And all you have to do is look at Chairman Dunford and the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and our combatant commanders to see that there is certainly in uniform a depth of experience that will serve this country, will serve the next president and the next administration.”

This story was originally published at 5:07 p.m. and updated after Mattis was sworn in and released his first public comments as defense secretary.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/checkpoint/wp/2017/01/20/senate-confirms-retired-gen-james-mattis-as-defense-secretary-breaking-with-decades-of-precedent/?utm_term=.00387eb5a88c&wpisrc=al_alert-COMBO-politics%252Bnation