Renan Koen first sat at a piano in Theresienstadt in 2018. For seven years prior, she played compositions written by internees at the hybrid concentration camp and ghetto near Terezin, the Czech fortress town that was occupied by Germans in World War II.

After 2018, she began making annual pilgrimages from Istanbul to this ghostly Czech town to hear its trees whisper between silences before performing lecture concerts from her 2015 album “Holocaust Remembrance / Before Sleep.”

“I really understood better, more deeply,” said Koen, an award-winning classical pianist and music therapist from Istanbul who started to honor her Jewish heritage with her 2014 album of Ladino songs, “Lost Traces, Hidden Memories.”

She advocates for Holocaust awareness in Turkey and beyond by performing the works of Jewish composers Gideon Klein, Viktor Ullman, Zikmund Schul and Pavel Haas, none of whom survived Nazi rule. “I understood the tempos more, the pace of life, where they walked.”

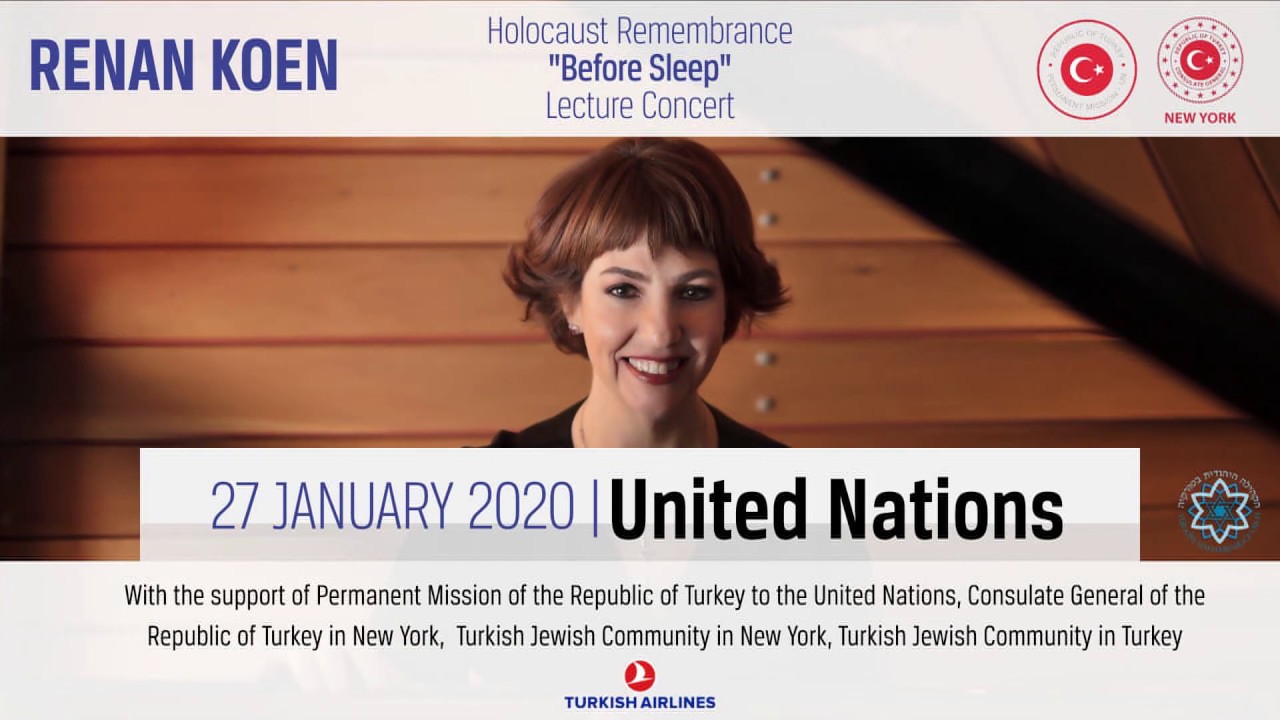

To commemorate International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27, Koen flew to New York to perform her “Holocaust Remembrance / Before Sleep” lecture concert under the auspices of the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations.

Before performing, her speech at the UN headquarters referred to the “brave Turkish diplomats who have saved the lives of many Jews,” just after Turkey’s permanent representative to the UN Feridun Sinirlioglu said, “Many righteous Turkish diplomats didn’t hesitate to risk their lives to save thousands of Jews.”

Sinirlioglu, a former ambassador of Turkey to Israel, likely knew that Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center has only named one Turkish national as a member of the Righteous Among the Nations, Israel’s official list of non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The only Turkish citizen named is Selahattin Ulkumen, who served as consul-general of Rhodes under German occupation.

Sinirlioglu and Koen left out a darker side to Turkey’s history with the Holocaust. While multiple Turkish diplomats leveraged their power to save Jewish lives, reportedly less than a hundred at a time, they were exceptions when Nazism, anti-Semitism and even Aryanism overwhelmingly influenced Turkish public policy and foreign affairs during World War II.

According to academic Corry Guttstadt, author of the “Turkey, the Jews and the Holocaust,” waves of legislation that passed in Turkey in 1938 followed Nazi anti-Jewish measures, particularly “Secret Decree No. 2/9498.”

“Beginning around the time the secret decree was issued, Turkey began to reject Jewish refugees even if they had passports. Turkish consulates demanded proof of ‘Aryan descent’ before granting an entry visa to Turkey,” Guttstadt wrote in the second volume of a book series published in 2016 by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), “Bystanders, Rescuers or Perpetrators? The Neutral Countries and the Shoah.”

For another academic, Rifat Bali, the statements by Koen and Sinirlioglu at the UN are emblematic of a tradition of miseducation about the Holocaust in Turkey.

“These are sweeping generalizations and exaggerations. This is part of the propaganda, where you repeat one false story thousands of times,” said Bali, publisher of Libra Books and the author of “Holocaust Consumption in Turkey: 1989-2017,” where he openly critiques Koen and her “Holocaust Remembrance / Before Sleep” project.

Since the 1980s, the government line of Holocaust reconciliation in Turkey is essentially a rescue myth, beginning in 1492, when Sultan Bayezid II invited Jews expelled from Spain to settle in the Ottoman Empire. History skews with the two points that follow, when praising Turkey for protecting Jewish refugees from the Nuremberg Laws, enacted by the Nazis to exclude German Jews from intermarriage and Reich citizenship, and the Final Solution, a policy of annihilation that resulted in the murder of 6 million Jews in Europe.

The refusal of Albert Einstein’s 1933 letter to Turkey, asking the Turkish Republic to accept 40 Jewish academics from Germany who would forgo remunerations for the first year, is a famous example of Turkey’s noncompliant neutrality.

For researchers Guttstadt, I. Izzet Bahar and Ilker Ayturk, the reality was grimmer.

In the IHRA volume, “Bystanders, Rescuers or Perpetrators?” Guttstadt and Bahar, along with colleagues Pinar Dost-Niyego and Nora Seni provide ample evidence for Turkey’s revocation of citizenship from Turkish Jews in Europe during Hitler’s rise.

“The examination of Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs documents reveals that during World War II, the Turkish government did not have any intention or make any attempts to protect the Jews of Turkish origin living in German-occupied Western Europe,” wrote Bahar, whose analysis of diplomatic correspondence also concluded that “Ankara was aware of the lethal conditions of the ongoing deportations to Eastern Europe.”

A slew of legislation had barred Turkish Jews from returning to Turkey, starting with the Turkish Citizenship Law of 1928, which effectively labeled about half of some 20,000 Turkish Jews in Europe as “irregular,” therefore illegible for repatriation. And for the approximately 75,000 Jews in Turkey, the socio-economic horizon had never been dimmer.

Despite the fact that certain Jewish academics did work in Turkey after 1933 — such as literary scholar Eric Auerbach and Assyriology expert Benno Landsberger — the 1932 Law on Activities and Professions in Turkey Reserved for Turkish Citizens made it hard for non-Turkish citizens to work in Turkey.

Still, as Guttstadt pointed out in the opening paragraphs of her chapter in the IHRA book — titled, “Turkey – Welcoming Jewish Refugees?” — Turkey accepted some 600 Jewish exiles from Germany between 1933 and 1939. The rise of Nazism coincided with Turkey’s push to modernize its universities, which required employing specialists from abroad, including 130 scholars the Nazis discriminated against for being Jewish.

In her 2020 paper, “Rescue or Rejection: Turkey’s Policies Towards Jews During the Holocaust,” published with the University of Sofia, Guttstadt outlined how the Settlement Law of 1934, passed that June, preceded pogroms in Thrace that raged until July, as some 15,000 Jews fled vandalization, rape and humiliation. The Wealth Tax of 1942, she argued, led to the expulsion of 1,870 mostly non-Muslim laborers to Askale, where 21 people died under the harsh conditions near the Russian border.

“Turkish Jews were particularly harshly hit by the tax, which impoverished many middle-class Jews, while those who could not pay the tax were sent to labor camps in eastern Turkey,” agree Ilker Ayturk and Dost-Niyego in their 2016 paper, “Holocaust Education in Turkey: Past, Present and Future.”

While it is clear that Koen is not a historian by discipline, she remains a prominent educator in the field of Holocaust awareness in Turkey, prompting initiatives with the Jewish Museum of Turkey and nongovernmental organizations like Civil and Ecological Rights Association (SEHAK).

“If you’re asking me what it’s like to work with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they’re very respectful about this issue [of Holocaust remembrance],” Koen said firmly, speaking at an Istanbul cafe not far from where she went to secondary school. “They don’t instrumentalize the issue. This is very important for me.”

As an independent artist, Koen collaborates with the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and such state sponsors as Turkish Airlines willingly, to the bafflement of critics like Bali, who has spent much of his career in letters exposing the persistence of anti-Semitism in Turkey. Yet looking back on his prolific body of work, which includes nearly 50 books and countless academic references, he determines that it has all amounted to nothing.

“If Koen is making positive headlines occasionally, I think that’s great,” Ayturk told Al-Monitor in an email. “There is no doubt that Turkey’s newly found interest in the Holocaust and desperate attempts to become a full member of IHRA are motivated by Turkey’s past with the Armenians and to curry favor with international public opinion by showcasing how (very few) Turkish diplomats helped Jews during the Holocaust.”

In their paper, “Holocaust Education in Turkey,” Ayturk and Dost-Niyego analyze Turkey’s bid for IHRA membership as a pivot to influence public opinion and international lobbyists by paying lip service to anti-Semitism and the Holocaust.

“I never play without an explanation. I start from the Holocaust,” Koen told Al-Monitor, about her “Holocaust Remembrance / Before Sleep” lecture concerts, which she also brings to students ages 11-17 in Turkey, and abroad, having traveled from the favelas of Brazil to Turkish schools in Germany. “The non-Jewish kids are more important for me because the Jewish schools can reach the source of history. The other doesn’t know.”

Koen teaches Holocaust awareness through music therapy. After playing compositions written in Theresienstadt, she asks her students to dialogue. She takes youth groups to Theresienstadt annually to compose music, write and make art in response to their experience, an initiative she calls “March of the Music,” to enact “Positive Resistance,” a concept she coined.

“My daughter goes to an Italian school. One of her subjects was the Holocaust in 5th grade. But with [Turkish] schools here this is really hard because it is not part of the curricula. When we talk about the Holocaust most of the time it is their first time,” Nisya Isman Allovi, director of the Jewish Museum of Turkey, told Al-Monitor.

The Jewish Museum of Turkey hosts schools, mostly imam-hatip religious students who have never encountered Jews or their history.

“At the Holocaust section [of the Jewish Museum of Turkey] we exhibit stories of diplomats who saved Turkish Jews, their passports, train tickets, the 1934 Thrace pogroms, and also prepare special exhibits,” said Allovi, who noted the museum’s display on the 1942 Struma disaster, referring to the Soviets’ sinking a ship carrying nearly 800 Jewish refugees after Istanbul refused it to port.

Koen plans to release an album with the Italian label Sheva Collection, featuring the students she has brought with her to Theresienstadt. They have prepared a new arrangement of a Gideon Klein string trio. The composer’s microtonal approach is also reflected in the music of Turkish composer Necil Kazım Akses, who studied with Alois Haba alongside Klein.

“If a person is not at peace individually, the community can’t be at peace. That’s why it’s very important to tell this history very transparently,” said Koen, who is currently performing a series of online concerts broadcast by the Turkish Jewish Community’s social media.