By Yannis Papadakis*

By Yannis Papadakis*

Familiar throngs of city people in a hurry. Everyone is walking fast, talking and texting on their phones. Stifling summer heat, the sun’s rays hammering down through the skyscrapers. Suddenly, Ι notice the strange figure of a man who could have likely descended from some parallel universe. I walk faster to approach him but his identity continues to bewilder me. I get even closer and notice how slowly he walks, the crowd flowing around him like a river while he is immersed in his world, observing silently, looking confused and out of place.

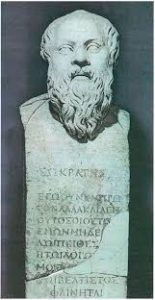

What a strange thing, I thought to myself, he looks like Socrates; and right when my rational sense was overdue for a comeback, he asks me if I know where the “Agora” is [1]. How bizarre, I recall thinking, something really strange is happening here. I slow down, the crowd-river is flowing now around us.

“Greetings, Teacher,” I say, “I had no idea you spoke such good English!”

“But I only speak Greek,” he retorts.

“Wait, didn’t you just ask me where the market was in perfect English?”

“Yes,” he says, “but it’s just that my old Greek coincides with your present-day English.” How strange…yet back in his day, Greek was as dominant as English is today. OK, I thought, this almost makes sense. I felt part of my sanity slowly coming back.

We are walking together silently amid the buzz of the crowd, in the blinding light of the New York summer.

But, my brain revolts, wait a minute, this can’t be happening, something doesn’t fit here.

“So, where is the Agora, you said?” he insists on knowing.

“Right here around us,” I respond, “see all these fancy shops and stores? They sell just about anything you could ever wish for.”

“I get all this,” he tells me, “but I do not see any philosophers teaching. Where are they? I’ve got to ask them some important questions. Are you yourself a philosopher and possibly hiding it?”

“Teacher, with all due respect,” I said, “I am not a philosopher. I just spotted you in the crowd and stopped to see if you needed help.”

“Your answer suffices,” he says, “the question is rhetorical so we can recognize each other in the mindless crowd; no philosopher in his right mind would ever admit being one anyway. May I ask where you are going?”

“To the bank” I say.

“Can I walk with you?”

“Of course,” I answer.

As we are getting out of the bank, “why”, he asks, “did the bank clerk not believe that you were you?”

As we are getting out of the bank, “why”, he asks, “did the bank clerk not believe that you were you?”

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“She wanted to see your ID card so she would be convinced that you are you; why did she do that? Isn’t the money in the bank yours?”

“Yes, of course the money is mine,” I replied, not sure where he was going with all those strange questions.

“Then how is it that they do not know you? And when you tell them you are who you say you are, how come your word is not good enough? Why do they need to see some external proof that you are indeed who you say you are?”

“OK, Teacher,” I said, “I think I understand where you are coming from; this is simply a matter of scale and efficiency. Yes, I realize how crazy it might seem to you that we are constantly trying to convince everyone and everything that we are indeed who we say we are.”

“So, without your ID you cannot get what is rightfully yours?” he insists.

“Unfortunately, my dear Teacher, this is the way things are,” I admitted. He frowned in frustration.

“And who decides what it takes to convince someone else that I am me?”

“The government decides that,” I answer. My response must have infuriated him because he raised the tone of his gruff voice even more.

“And what interest does a democratic government have in putting hurdles on its citizens who want to convince their fellow citizens that they are who they say they are?”

“Teacher, you are really putting me on the spot,” I said, vying for time. “This is done for the safety of everyone and to avoid situations that would run against the law.”

What followed my response was a rare moment of silence.

“Well,” he said thoughtfully, taking a deep breath, “how is this pattern of requiring an ever-stronger proof of each citizen’s identity supposed to end? What can ever be considered good enough? Where does this stop for the citizen, the government or the city? Birth certificates, social security numbers, IDs, fingerprints, passports, passwords, biometric data, tracking chips and even chip implants…why are you telling me that the path of growing mistrust among citizens also happens to be the one desired, so that the city achieves scale and efficiency? What does it mean when scale and efficiency skyrocket in your city while any sense of trust between its citizens or with their government is rendered meaningless? What good are your shiny skyscrapers when it is neither meaningful nor worthwhile to trust another fellow citizen?”

“We have not found a better way,” I said timidly. I realize quickly that my answers are to no avail; he seems to get more outraged with each response, so I desperately look for a way out of this terrible predicament.

“My sincere apologies,” I said, “but I really need to be heading home, I hope you understand.” And I start to walk toward the station. He follows at close distance, I’m walking faster and faster, but he’s rapidly firing questions at me like RPG’s.

“Why do citizens accept such a growing mistrust? How can they love their future in this city? Where are those who are supposed to correct these flaws? Where are all the philosophers and poets hiding?”

He is screaming at me at the top of his lungs, I am running as fast as I can, moving at the speed of nightmare; the subway finally comes – I am saved. There’s just enough trust left in me to lose myself in the mindless, anonymous crowd.

* Yannis Papadakis (PhD, Electrical Engineering) lives and works in the United States.

[1] “Agora”, pronounced /aɡəˈrä/, written in Greek as “Αγορά” was the most central place of every ancient Greek city, a cross between a modern flea-market and a “speakers’ corner” where philosophers and others would lecture in public. The reader can find more general information about the ancient Agora of Athens at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Agora_of_Athens. It should be noted that the American School of Classical Studies (ASCS) has done extensive archaeological research at the site of the ancient Agora of Athens, see https://www.ascsa.edu.gr/publications/books/open-access-books/athenian-agora-oa . Special mention should be given to an ASCS publication titled “Socrates in the Agora”. There the authors combine findings from the archaeological excavations at the Agora with Plato’s dialog “Phaedo” to conclude that the the cell where Socrates was held prisoner and died by drinking hemlock can be uniquely identified. The entire publication can be accessed online at http://www.agathe.gr/Icons/pdfs/AgoraPicBk-17.pdf (see pages 29-33 for an illuminating discussion of the Agora state prison).

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my daughter, Arianna Papadakis, whose thorough review and thoughtful edits greatly improved the readability of this essay.