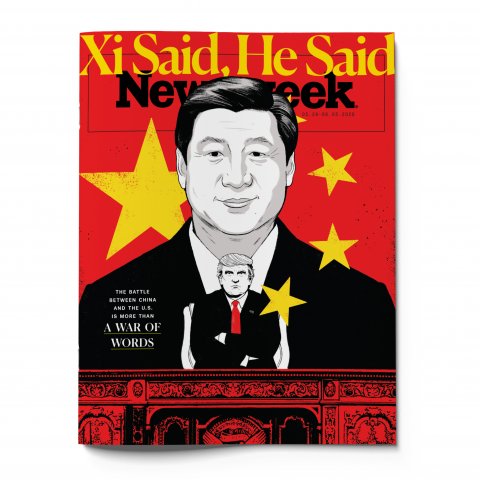

Newsweek

Newsweek

It had been a bedrock belief of U.S. policy for 40 years that it was possible to bring the People’s Republic of China smoothly into the family of nations—and now, one of the architects of that policy was finally acknowledging the obvious.

In a speech six months ago, former World Bank President and Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick reminded listeners of his own famous 2005 call on Beijing to become a “responsible stakeholder.” He ticked off a few of the ways in which China had done just that: voting for sanctions on North Korea and limiting missile exports, for instance. But he acknowledged that the project had gone off the rails.

“Xi Jinping’s leadership,” Zoellick said of the PRC president, “has prioritized the Communist Party and restricted openness and debate in China. China hurts itself by forging a role model for dystopian societies of intrusive technologies and reeducation camps.” He added: “The rule of law and openness upon which Hong Kong’s ‘One Country, Two Systems’ model rests may topple or be trampled. If China crushes Hong Kong, China will wound itself—economically and psychologically—for a long time.”

Zoellick had that right. A global pandemic has brought relations between Beijing and Washington to its lowest point since China reopened to the world in 1978—even lower even than in those extraordinary days following the 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

What had been a more confrontational, trade-centric relationship since the start of President Donald Trump’s term, has now descended into bitterness in the midst of a presidential reelection campaign Trump fears is slipping away. Any chance that the pandemic might spur Washington and Beijing to set differences aside and work together on treatments and other aspects of the pandemic—such as how exactly it started—is long gone.

Last week, the Trump administration moved to block shipments of semiconductors to Huawei Technologies. The Commerce Department said it was amending an export rule to “strategically target Huawei’s acquisition of semiconductors that are the direct product of certain U.S. software and technology.” Previously on May 13, the FBI announced an investigation into Chinese hackers that it believes are targeting American health care and pharmaceutical companies in an effort to steal intellectual property relating to coronavirus medicines. Without specifying how, the Bureau said the hacks may be disrupting progress on medical research.

President Trump had already made it clear just how bitter he is at Beijing on May 7 when meeting with reporters at the White House. “We went through the worst attack we’ve ever had on our country,” he said, “this is the worst attack we’ve ever had. This is worse than Pearl Harbor, this is worse than the World Trade Center. There’s never been an attack like this. And it should have never happened. Could’ve been stopped at the source. Could’ve been stopped in China…And it wasn’t.” The comparison of a virus, which originated in China and then spread globally, to the two most infamous attacks in U.S. history, stunned Trump’s foreign policy advisers—even Beijing hard-liners. It will be impossible, U.S. officials acknowledge, for Trump to soften his hard line toward Beijing should he win reelection in November.

The president is right to reach for historical metaphor, given the weight of the moment. But the aftermath of the Wuhan outbreak more closely resembles the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 than either Pearl Harbor or 9/11. What follows will not be a sharp burst of savage conflict, but a global scramble to shape the new order rising from the rubble of old. As with the Wall, the forces that led to the dispute over the Wuhan outbreak were unleashed years before the events that made history. And the change they represent is likely irreversible, no matter who sits in the White House.

Though Joe Biden has on occasion downplayed Beijing’s rise as a threat to the U.S., and for sure would not be so rhetorically reckless as Trump, his foreign policy advisers acknowledge there’s no turning back. Since Xi Jinping came to power seven years ago, China has imprisoned more than one million ethnic Muslims in “reeducation” camps, imposed an ever-tightening surveillance state on its own citizens and cracked down on all dissent. Overseas, Beijing’s goal is to entice authoritarian regimes in the developing world to view it as a “model” to be followed. And, of course, selling the technology those leaders need to create their own surveillance states.

“No one on either side of the political aisle in Washington is ignoring any of that,” says one Biden adviser. “The era of hope that China might evolve into a normal country is over. No one with any brains denies that.”

That notion has fully settled in here. Sixty-six percent of Americans now have a negative view of China, according to a recent Pew Research poll. At the same time, in China, state-owned media and a government-controlled internet whip up nationalism and anti-Americanism to levels unseen since the U.S. accidentally bombed Beijing’s embassy in Belgrade during the Balkan wars in 1999.

The world’s two most powerful nations are now competing in every realm possible: militarily, for one, with constant cat-and-mouse games in the South China Sea and cyber warfare. The competition to dominate the key technologies of the 21st century is intensifying, too. This type of rivalry hasn’t been seen since the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Thus, a growing number of policymakers, current and former, and China hands old and new, acknowledge the obvious: Cold War 2.0 is here. To the generation of Americans who remember duck-and-cover drills in elementary school at the peak of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the new global struggle will look very different. It will also, many U.S. strategists believe, be much harder for the West to wage successfully. “Another long twilight struggle may be upon us,” says former Pentagon China planner Joseph Bosco, “and it may make the last one look easy.”

Now, U.S. policymakers are trying to discern what that struggle will look like, and how to win it.

New-Age War

The first major difference in the coming Cold War with Beijing is in the military realm. Beijing spends far less than the U.S. on its military, though its annual rate of spending is fast increasing. According to the Center For Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, Beijing spent $50 billion on its military in 2001, the year it joined the World Trade Organization. In 2019 it spent $240 billion, compared to the U.S.’ $633 billion.

For a few decades at least, the U.S.-China military competition will look vastly different from the hair-trigger nuclear standoff with Moscow. Instead, China will seek asymmetric advantages, rooted where possible in technology. It has, for example, already developed an arsenal of hypersonic missiles, which fly low and are hard for radar to detect. They are known as “carrier killers” because of their ability to strike U.S. aircraft carriers in the Pacific from long distances. These weapons could be critical in “area denial” operations, as military planners put it. For example, should the day come when Beijing seeks to take Taiwan by force, hyper-sonics could keep U.S. carriers far from the island nation once a war began.

China’s pursuit of preeminence across a wide range of technologies, in areas like quantum computing and artificial intelligence, are central to the economic clash with the U.S. But they also have significant military components. Since the 1990s, when Chinese military planners were stunned by the U.S.’ lightning victory in the first Iraq war, they have consistently focused their efforts on developing war-fighting capabilities relevant to their immediate strategic goals—Taiwan is an example—while creating the ability to one day leapfrog U.S. military technologies.

That may be drawing nearer. Quantum computing is an example. In an era in which digital networks underpin virtually every aspect of war, “quantum is king,” says Elsa Kania, a former DOD official who is now a Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security. Take cyber warfare—the ability to protect against an enemy disrupting your own networks, while maintaining the ability to disrupt the adversary’s. Quantum networks are far more secure against cyber espionage, and Kania believes China’s “future quantum capacity has the potential to leapfrog U.S. cyber capabilities.”

That’s not the only advantage of quantum technology. Beijing is also exploring the potential for quantum-based radar systems that can defeat stealth technology, a critical U.S. war-fighting advantage. “These disruptive technologies—quantum communications, quantum computing and potentially quantum radar—may have the potential to undermine cornerstones of U.S. technological dominance in information-age warfare, its sophisticated intelligence apparatus, satellites and secure communications networks and stealth technologies,” says Kania. “China’s concentrated pursuit of quantum technologies could have much more far-reaching impacts than the asymmetric approach to defense that has characterized its strategic posture thus far.” That is a big reason why Pan Jianwei, the father of China’s quantum computing research effort, has said the nation’s goal is nothing less than “quantum supremacy.”

Washington, and its allies in East Asia and Europe, are paying attention. In a just-published book—The Dragons and the Snakes: How the Rest Learned to Fight the West—David Kilcullen, a former Australian military officer who served as special adviser to U.S. General David Petraeus in Iraq, writes: “our enemies have caught up or overtaken us in critical technologies, or have expanded their concept of war beyond the narrow boundaries within which our traditional approach can be brought to bear. They have adapted, and unless we too adapt, our decline is only a matter of time.”

The book is being widely read in U.S. national security circles.China is not yet a “peer power,” as U.S. national defense analysts put it. But the steadily aggressive pursuit of quantum technologies—and a wide array of others that also have dual-use applications—increasingly convince Pentagon planners that Beijing will one day be one. China, says Michael Pillsbury, one of Trump’s key informal advisers on relations with Beijing, “is nothing if not patient.” The year 2049 will mark the Chinese Communist Party’s 100th anniversary of taking power in Beijing. That’s the year Chinese propaganda outlets have said will see the completion of China’s rise to the dominant power on earth.

An Economic Divorce?

The most significant difference in the emerging geopolitical standoff between Washington and Beijing is obvious: China is economically powerful, and deeply integrated with both the developed and developing worlds. That was never the case with the former Soviet Union, which was largely isolated economically, trading only with its east bloc neighbors. China, by contrast, trades with everyone, and it continues to grow richer. It is sophisticated across a wide range of critical technologies, including telecommunications and artificial intelligence. It has set as a national goal—in its so-called Made in China 2025 plan—preeminence not just in quantum computing and AI, but in biotech, advanced telecommunications, green energy and a host of others.

But the U.S. and the rest of the world have problems in the present as well. The pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of locating supply chains for personal protective equipment as well as pharmaceutical supplies in China. That’s a significant strategic vulnerability. If China shut the door on exports of medicines and their key ingredients and raw material, U.S. hospitals, military hospitals and clinics would cease to function within months if not days, says Rosemary Gibson, author of a book on the subject, China Rx. Late last month, Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton introduced legislation mandating that U.S. pharmaceutical companies bring production back from China to the U.S.

China’s explicit desire to dominate the industries of the future is bad news for foreign multinational companies that have staked so much on the allure of the China market. If China’s steep rise up the technology ladder continues, American and other foreign multinationals are likely to get turfed out of the market entirely. “China 2025 is all about replacing anything that American companies sell of any value, just taking the Americans out of that,” says Stewart Paterson, author of China, Trade and Power, Why the West’s Economic Engagement Has Failed.

Donald Trump’s tariffs, and China’s public desire to dominate key industries, have pushed American multinational and U.S. policymakers to ask: should the U.S. get an economic divorce from Beijing? And if so, what would that look like?

The COVID-19 outbreak and China’s response to it has greatly intensified that debate. Trump’s trade war had triggered a slow-motion move toward an economic “decoupling,” as companies in low-tech, low- margin industries began to move production out of China to avoid tariffs. The textile, footwear and furniture business have all seen significant movement out of China so far. But pre-pandemic, there was no mad rush for the exits and there was no reason to expect one anytime soon. As recently as last October, 66 percent of American companies operating in China surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce in Beijing said “decoupling” would be impossible, so interlinked are the world’s two largest economies.

Things have changed. The number who now believe decoupling is impossible, according to the same survey, has dropped to 44 percent. If reelected, Trump’s advisers say, the president will likely pressure other industries beyond pharmaceuticals and medical equipment to bring back production. How he would actually do that is unclear, but aides are looking at the example of Japan. The Japanese legislature recently approved a program in which the government will offer subsidies—up to $2.25 billion worth—to any company that brings its supply chain back home.

As negative perceptions of China harden in the U.S., executives are faced with a stark choice: as Paterson puts it, “do you really want to be seen doing business with an adversary?”

The answer isn’t that easy. In the U.S., a lot of companies simply do not want to reduce their exposure to China. They spent years—and billions—building up supply lines and are loath to give them up. Consider the semiconductor industry, a critical area in which the U.S. is still technologically more advanced than China. A complete cessation of semiconductor sales to China would mean U.S. firms lose about 18 percent of their global market share—and an estimated 37 percent of overall revenues. That in turn would likely force reductions in research and development. The U.S. spent $312 billion on R&D over the last decade, more than double the amount spent by its foreign competitors—and it’s that R&D which allows them to stay ahead of competitors.

Paterson argues that the costs of total divorce from China is often overstated. He calculates that about 2 percent of U.S. corporate profits come from sales in the Chinese market, mostly from companies that manufacture there in order to sell there. Corporate profits overall are 10 percent of U.S. GDP. Eliminating the China portion of that “is a rounding error,” he says.

But getting companies such as Caterpillar Inc., which operates 30 factories in China and gets 10 percent of its annual revenue from sales there, is an uphill lift. There are scores of companies like Caterpillar, who have no intention of leaving China, even if relations between Washington and Beijing are at new lows. And there are also scores of companies like Starbucks, which operates 42,000 stores across China, or Walmart, whose revenue in the country is more than $10 billion annually. Those companies don’t have critical technology to steal and may be little worry to the U.S. if they continue to operate in China.

But other companies do. Tesla, to take one example, is a company whose advanced technology should be protected at all costs. Which is why some in Washington are scratching their heads at both Elon Musk and the Trump administration. Musk said on May 10th that he was so angry at the shutdown orders in the state of California, he might move the Tesla factory in Fremont to Texas. Meanwhile, he manufactures his cars in Shanghai, which is an obvious target for intellectual property theft and industrial espionage, given that electric vehicles are one of the industries targeted in the China 2025 plan. “California bad, Shanghai good is not a formulation that’s going to hold up well in the post-COVID environment,” says Paterson.

A smarter U.S. strategy than “divorce” is “economic distancing,” says John Lee, a Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute, a Washington think tank. The goal of U.S. industrial policy should be “ensuring that China is not in a position to dominate key technologies and assume the leading role in dominating supply and value chains for these emerging technologies,” he says. Rationing access to large and advanced markets is critical. “It becomes much more challenging [for Beijing] if China’s access to markets in the U.S. Europe and East Asia is restricted, and it is denied key inputs from those areas.”

That presumes coordination with allies, which has not been a Trump administration strong suit. But that would change under a President Joe Biden. Even before the pandemic, key European and Asian allies were souring on their relations with China. That includes Canada as well. A former senior Canadian official said Ottawa wanted to work with Trump and the Europeans to map out a tougher, united front on trade. The only problem? “You were sanctioning our steel exports on ‘national security grounds,'” this official says. “We are a NATO ally, for godssake!”

The opportunity to work more closely to form a united front versus Beijing is something Biden advisers are intent on doing. A reconfigured Trans Pacific Partnership, which Barack Obama pushed, is likely the first order of business in a Biden administration—this time more explicitly targeted at excluding Beijing from free trade deals among U.S. allies.

That is, if there is a Biden administration.

What’s Next?

In the context of the new Cold War, the move toward a smart economic distancing, as Hudson’s Lee and others call for, will gain momentum. “Washington put too much faith in its power to shape China’s trajectory. All sides of the policy debate [in the U.S.] erred,” says Kurt Campbell, former assistant secretary of state under Obama. Biden’s people are already spreading the word that there will be no return to the laissez faire attitudes that governed Washington’s approach to China. The U.S. may also have to overtly subsidize companies in the Made in China 2025 industries that Beijing has targeted.

Beijing had resisted suspending its own industrial subsidies to state-owned industries in the Trump trade negotiations and had shown few signs of backing off from the goals expressed in Made in China 2025. In the wake of the global fury kicked up by the coronavirus, an economic rapprochement appears unthinkable.

Militarily and geopolitically, no matter who wins the next election, the U.S. will work hard to bring India, which has hedged its bets between Washington and Beijing as China rose, more closely into the fold of a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” as the Trump administration has called its policy toward Asia. The ability to work more closely with allies, both in East Asia and in Europe, in creating a united front against Beijing has never been stronger.

“No one that we talk to is happy,” says Rand Corporation’s Scott Harold.

What many look for is steadier and clearer public messaging from Washington. As Harold puts it, as the ideological competition with Beijing intensifies, “the defenders of the liberal international order, like-minded democracies, should grow more active in defense of their interests and values.”

In the wake of the pandemic, the U.S. is suffering a defeat that should be unthinkable: it is losing the propaganda war, particularly in the developing world. Both internally and abroad, the Chinese Communist party’s propaganda outlets, digital and broadcast, are trumpeting Xi Jinping’s handling of COVID-19, and contrasting it with the Trump administration’s shambolic efforts to deal with the virus. State media outlets chronicled how badly the U.S. and others have managed the crisis. Their message: Those countries should copy China’s model.

As competition between the United States and China grows, the information wars will be critical. In this, the “America First” Trump administration has been mostly AWOL—the President has not been able to rouse himself to support pro-democracy demonstrators in Hong Kong, so desperate was he for a trade deal with Xi Jinping. But, Trump and Biden have some good role models and, thus, there’s hope. U.S. presidents have defended the country’s values quite well, and steadily, throughout the last Cold War, none more ably than Ronald Reagan, who left office a year before the Berlin Wall came down.

We will see, of course, if the next administration is up for the fight. Washington has at least recognized, as Kurt Campbell observes, that it overvalued its ability to influence China’s development” Presumably it won’t make that mistake again. Instead, Washington and its allies need to focus more on how to cope effectively with a powerful rival.

The mission: Wage the 21st century’s Cold War, while ensuring it never turns hot.

Newsweek