Recent disputes in the Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey are of a persistent nature. In addition to the centuries-old, love/hate relationship between the two people, the two NATO-allied states are rivals over natural resources research in the Aegean Sea, the island of Cyprus and different interpretations of international treaties related to the sea. The dispute takes on a geopolitical turn, since both countries want the upper hand in the Aegean Sea and the neighboring region.

The Treaty of Lausanne, which was signed and ratified in 1923, ended the European military presence in Turkey and the military conflict between Greece and Turkey. It guaranteed the independence of the latter, and most importantly, divided the land and especially the islands between the two. As a result of the Treaty, Greece maintained sovereignty over most of the islands of the Aegean Sea, some of which are located hundreds of kilometers from the Greek mainland and a few kilometers from the shores of Turkey.

The recent maritime dispute between the two states is related to this division of islands as well as to the importance of natural resources which both countries aim to guarantee. The legal dimension is an important part of this dispute too, especially due to the presence of a number of international agreements related to the maritime problems between states, mainly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Turkey aims to amend the Lausanne Treaty, which gave Greece sovereignty over the archipelago of islands close to the Turkish coast, as well as to benefit from the process of exploration and extraction of natural resources from the sea, which is difficult in the event of continued Greek sovereignty over the islands. As for Greece, it aims to keep the status quo since control over the islands gives Athens the upper hand in the Aegean Sea.

The following will dig deep into the Turkish-Greek dispute over the Aegean Sea and will present the geopolitical importance of the archipelago of islands that Athens controls near the Turkish shores. Additionally, the dispute will be analyzed from a legal perspective over rights in the waters. Moreover, this article will not lose sight of Turkish tendencies to revise the Lausanne Treaty, both states’ maritime capabilities and the role of international powers.

Greek-Turkish Hostilities and the Geopolitical Importance of the Greek Archipelago

The hate and distrust between Greece and Turkey are reflected in their common history and the many conflicts that have occurred throughout their histories. Scholars often disagree on the exact date of no return of a friendly relationship between Greece and Turkey. Some set the date in 1831 and the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire, while others set the date of 1912—the start of the First Balkan War followed by direct military confrontations between the two sides during and after World War I and throughout modern history. However, historians agree that “enmity is more a natural status in their relationship.”1

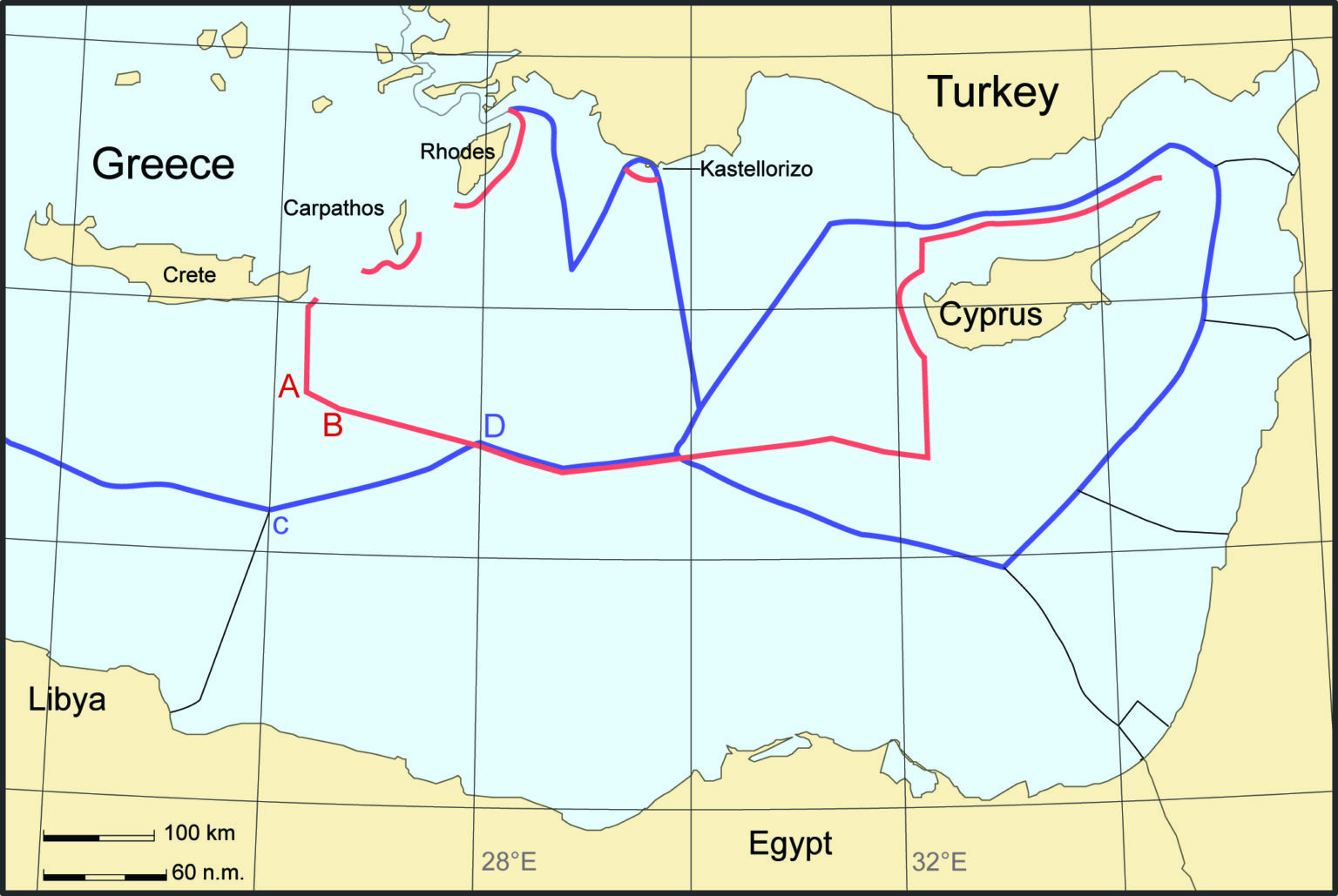

The most important recent conflicts between the two neighboring countries were in 1974. That’s when Ankara controlled the northern part of Cyprus and loosened Athens’ grip over the island. In 1976, 1987 and 1996, Greek and Turkish provocative steps in the Aegean Sea almost led to military hostilities.2 In 2020, the two sides were on the brink of a war once again when Turkey sent commercial and other types of ships to search for natural resources near the tiny Greek island of Kastellorizo. This provocation by Turkey angered Greece, which deemed the move as a violation of its maritime sovereignty. In retaliation, Athens sent its ships to explore natural resources in the same place. The matter nearly reached the limits of military clashes had it not been for the intervention of European powers to calm the two sides.

Both countries emphasize the strategic importance of the archipelago of islands that Greece holds today. Estimated by the hundreds, these islands close to the Turkish mainland are geopolitically significant from their positioning, as well as their roles in case of a military confrontation. Despite being demilitarized according to international treaties, these islands can become an advanced military site working in favor of Greece and obstruct Turkish movement. The islands are also part of the commercial maritime route the Turks have to take today in order to avoid passing through Greece’s maritime waters surrounding the islands for many nautical miles.

The main geopolitical importance of the Greek archipelago near the Turkish mainland is that it enables Greece to explore around it for natural resources. According to international laws and Greek claims, the archipelago also gives Athens vast areas of the Aegean Sea to serve as an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). However, if these islands were not under Greek sovereignty, Greece and Turkey would have shared equally the EEZs as well as the continental shelves.

Greece also receives tourism revenues and uses the islands as primary and advanced barriers to prevent refugees and smugglers from entering the Greek mainland.

The UNCLOS and the States’ Rights in Waters

Since the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, Greece has controlled almost all of the islands in the Aegean Sea. Most of these islands are uninhabited and considered to be rocks, stipulating no maritime rights for Greece according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).3 Other islands, such as the inhabited Kastellorizo, are up to two kilometers from Turkish shores and 570 kilometers from the Greek mainland.

According to Turkish national rhetoric, this ‘uneven’ geographical division of the islands leads Ankara to increase its demands in the sea, and in return, leads its counterpart to reject them. The recent dispute between the two neighbors takes media and aggressive political statements as tools to defend claims, the army and naval force as means of intimidation and pressure, and the international laws as references to proclaim rights.

Within the legal framework, the two parties disagree on four basic matters: territorial waters, EEZs, continental shelves and island rights. Only the latter will be focused on in this paper.

The main reason for this radical legal disagreement stems from the fact that Turkey, unlike Greece, is one of the few states that did not sign the UNCLOS, and therefore is not obliged to abide by its rules, but rather choose old treaties, conventions and international customs as legal references to proclaim rights in the Aegean Sea.

Before signing the UNCLOS, states like Turkey and Greece abided by the six nautical miles in the Aegean Sea. The Convention, however, allows Greece to extend its territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles from its shores, but it refrained from doing so until today. If Athens does apply the 12 nautical miles and proclaim additional territorial waters, Greece will have, according to the UNCLOS, sovereignty on waters very close to the Turkish shores. Greek islands, such as Kastellorizo, Lesbos, Chios, Samos and the Dodecanese islands, will expand Greece’s sovereign waters, which means a decrease in Turkish sovereignty over its territorial waters in areas that, in many cases, do not exceed a distance of one kilometer from its shores.

From Ankara’s point of view, customary laws apply to the Aegean Sea when it comes to the Greek islands’ status, since Turkey is not part of the UNCLOS. Turkey often declares that the change of the status quo of the islands will mean a casus belli and an aggression on its territorial waters.4

Even though the UNCLOS allows Greece to proclaim more territorial waters and Turkey often uses the 12 nautical miles in other surrounding seas such the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, both states just declare intentions to change the status quo in the Aegean Sea’s islands but without practically doing anything that might threaten the security and stability of the entire region.

In 2020, the two sides were on the brink of a war when Turkey and Greece both sent commercial and military ships to search for natural resources near the tiny Greek island of Kastellorizo. Greece saw the move as a violation to its maritime sovereignty. European powers were alerted for a potential military clash between the two neighboring countries.

Turkey was exploring for natural resources at a point about 6.5 nautical miles away from the island of Kastellorizo, which is considered by the Greek side to be in its territorial waters (if 12 nautical miles would be applied, or in its exclusive economic zone if the 12 nautical miles is not applied). As for the Turkish side, it has an opposite point of view, as it considers it unfair for Greece to obtain absolute sovereignty over the waters directly near Turkish borders, and, accordingly, prevents it from exercising sovereignty over its own territorial waters.

Turkish Quest to Override the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne was signed and ratified in 1923 between Turkey and many other nations, including the US, Japan, Italy, Britain, France, Yugoslavia, Romania, and most importantly, Greece. It is a treaty of peace that stipulated the following:

- The independence of Turkey was proclaimed.

- The borders of Turkey were defined and internationally recognized. Turkey abandoned its claims in later-Iraqi Mosul city, pieces of Western Thrace, and most islands near the Turkish shores.

- Greece’s sovereignty over the islands near the Turkish border was legitimized and internationally recognized.

- Greek-Turkish exchange of population took place. Orthodox Greeks living inside newly-established Turkish borders were exchanged for Muslim Turks living in Greece.

- Civilian passage was guaranteed through the Turkish Dardanelles and Bosporus straits.5

It is fair to say that the Treaty of Lausanne achieved the independence of the Turkish Republic, but it determined the limits of Turkish political, geographical and geopolitical action in its regional sphere especially since the years following the ratification of the treaty witnessed a balance of power between Athens and Ankara.

The last 20 years of the Justice and Development Party in Turkey saw an advance in Turkish economy, demography, military, cultural and political influence, etc. This led to a growing feeling among Turks and the Turkish political leadership on the necessity to override the Lausanne Treaty, which defined the limits of Turkey’s regional movements and actions, especially in the Aegean Sea.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan often mentions the quest of his country to override the Treaty. During a visit to Athens in 2018, he declared that “over time all treaties need a revision – the Lausanne Treaty, in the face of the recent developments, needs a revision.” His Greek counterpart, former president Prokopis Pavlopoulos, replied that “the Treaty of Lausanne is a treaty which leaves no loopholes in terms of bilateral relations, which does not require completion and which includes no ambiguities on regional borders or models. We do not consider it to be a treaty which should be discussed, reviewed or reformed.”

In other words, Turkey sees that its current superiority as a regional power over Greece should be translated into the treaty that governs the relationship between the two states. Greece aims to preserve the status quo, while Turkey wants to override the treaty which limits its superiority over Greece.

To date, Turkey has not amended any of the treaty clauses in order to increase and legitimize its strategic influence in the Aegean Sea, mainly over the islands in the Greek archipelago. This might be due to the fear of European and international rejection that does not accept overriding international treaties that could destabilize international peace and security.

Greek-Turkish Maritime Powers: A Sea Arm Race?

A primary aspect of the recent dispute between Greece and Turkey over the archipelago and the Aegean Sea is related to natural resources that might be found in the sea. Greece needs oil and gas in order to support its economy, while Turkey badly needs it in order to balance between its exports and imports and reduce its trade deficit where almost all of the value of its national production goes to finance the purchase of oil and gas from Russia, Iran, Iraq, etc.6

In order to protect their interests in the Aegean Sea, as well as the profits to be gained from exploration and drilling for natural resources in the future, Greece and Turkey seek to enhance their naval military capabilities while European powers often engage in diplomatic talks and initiatives in order to reduce the tension between the two.

During the last three years, Athens has worked on updating its naval capabilities. It aims to purchase German and French submarines, vessels and frigates. These “partnerships proved successful in providing the navy with efficient, well-armed vessels while also allowing Greece to maintain a modest yet capable shipbuilding industry.” In comparison to the Turkish capabilities, the Greek navy needs to be fortified. Ankara developed its naval power more rapidly and with advanced technology. “Ankara is building a navy that characterizes a regional power and can conduct long-range operations… the Turkish Navy should certainly be considered a green-water Navy that can operate far beyond the country’s shores.”

Both countries are purchasing new sea war machines in order to be ready for any clash as well as to quest for strategic military superiority in the Aegean Sea. Due to both countries’ economic needs and other geopolitical interests, a very minimal arms race appears to be developing between the two states with an advantage for the Turkish side.

US and European powers often initiate talks between the two in order to ease the tension in the region and to secure a region typically anti-Russian. The western world cannot bear a war between Greece and Turkey—two NATO members—in a time where Russian and Chinese influence is increasing in both Europe and Asia and across the Mediterranean.

Greece and Turkey share a long history of enmity and compete over many issues. Greece wants to preserve the status quo while Turkey aims to change it in order to legitimize its strategic superiority.

Ankara aims to override the Lausanne Treaty but has not done much to date for fear of initiating international reactions. But Turkey is taking new leaps in developing and upgrading its naval power in comparison to Greece.

Both states aim to secure desperately needed natural resources in the Aegean Sea. Therefore, the sovereignty over the archipelago of islands near the Turkish shores holds an important strategic meaning for both states. If Greece continues its dominance and sovereignty in the area, Athens will have more waters to explore and from which to extract oil and gas, while Ankara will be left with few areas to work unless it introduces changes to the Lausanne Treaty.

_________________

1 Alexis Heraclides, The Greek-Turkish Conflict in the Aegean: Imagined Enemies, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2010, p. 3.

2 Haralambos Athanasopulos, Greece, Turkey and the Aegean Sea: A Case Study in International Law, McFarland & Company Inc. Publishers, North Carolina, 2001, pp. 10-76.

3 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Part VIII, Article 121.

4 Alexis Heraclides and Gizem Alioğlu Çakmak, Greece and Turkey in Conflict and Cooperation: From Europeanization to De-Europeanization, Routledge, Oxon, 2019, p. 99.

5 Société des Nations, “Recueil des Traités”, Vol. XXVIII, No. 1,2,3,4, 1924, pp. 151-171.

6 Erkan Özata, “Sustainability of current account deficit with high oil prices: Evidence from Turkey”, International Journal of Economic Sciences, Vol. 3, No 2, 2014, pp. 72-75.