Even to mention the 1930s is to evoke the period when human civilisation entered its darkest, bloodiest chapter. No case needs to be argued; just to name the decade is enough. It is a byword for mass poverty, violent extremism and the gathering storm of world war. “The 1930s” is not so much a label for a period of time than it is rhetorical shorthand – a two-word warning from history.

Witness the impact of an otherwise boilerplate broadcast by the Prince of Wales last December that made headlines: “Prince Charles warns of return to the ‘dark days of the 1930s’ in Thought for the Day message.” Or consider the reflex response to reports that Donald Trump was to maintain his own private security force even once he had reached the White House. The Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman’s tweet was typical: “That 1930s show returns.”

Because that decade was scarred by multiple evils, the phrase can be used to conjure up serial spectres. It has an international meaning, with a vocabulary that centres on Hitler and Nazism and the failure to resist them: from brownshirts and Goebbels to appeasement, Munich and Chamberlain. And it has a domestic meaning, with a lexicon and imagery that refers to the Great Depression: the dust bowl, soup kitchens, the dole queue and Jarrow. It was this second association that gave such power to a statement from the usually dry Office for Budget Responsibility, following then-chancellor George Osborne’s autumn statement in 2014. The OBR warned that public spending would be at its lowest level since the 1930s; the political damage was enormous and instant.

In recent months, the 1930s have been invoked more than ever, not to describe some faraway menace but to warn of shifts under way in both Europe and the United States. The surge of populist, nationalist movements in Europe, and their apparent counterpart in the US, has stirred unhappy memories and has, perhaps inevitably, had commentators and others reaching for the historical yardstick to see if today measures up to 80 years ago.

Why is it the 1930s to which we return, again and again? For some sceptics, the answer is obvious: it’s the only history anybody knows. According to this jaundiced view of the British school curriculum, Hitler and Nazis long ago displaced Tudors and Stuarts as the core, compulsory subjects of the past. When we fumble in the dark for a historical precedent, our hands keep reaching for the 30s because they at least come with a little light.

The more generous explanation centres on the fact that that period, taken together with the first half of the 1940s, represents a kind of nadir in human affairs. The Depression was, as Larry Elliott wrote last week, “the biggest setback to the global economy since the dawn of the modern industrial age”, leaving 34 million Americans with no income. The hyperinflation experienced in Germany – when a thief would steal a laundry-basket full of cash, chucking away the money in order to keep the more valuable basket – is the stuff of legend. And the Depression paved the way for history’s bloodiest conflict, the second world war which left, by some estimates, a mind-numbing 60 million people dead. At its centre was the Holocaust, the industrialised slaughter of 6 million Jews by the Nazis: an attempt at the annihilation of an entire people.

In these multiple ways, then, the 1930s function as a historical rock bottom, a demonstration of how low humanity can descend. The decade’s illustrative power as a moral ultimate accounts for why it is deployed so fervently and so often.

Less abstractly, if we keep returning to that period, it’s partly because it can justifiably claim to be the foundation stone of our modern world. The international and economic architecture that still stands today – even if it currently looks shaky and threatened – was built in reaction to the havoc wreaked in the 30s and immediately afterwards. The United Nations, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, Bretton Woods: these were all born of a resolve not to repeat the mistakes of the 30s, whether those mistakes be rampant nationalism or beggar-my-neighbour protectionism. The world of 2017 is shaped by the trauma of the 1930s.

One telling, human illustration came in recent global polling for the Journal of Democracy, which showed an alarming decline in the number of people who believed it was “essential” to live in a democracy. From Sweden to the US, from Britain to Australia, only one in four of those born in the 1980s regarded democracy as essential. Among those born in the 1930s, the figure was at or above 75%. Put another way, those who were born into the hurricane have no desire to feel its wrath again.

Most of these dynamics are long established, but now there is another element at work. As the 30s move from living memory into history, as the hurricane moves further away, so what had once seemed solid and fixed – specifically, the view that that was an era of great suffering and pain, whose enduring value is as an eternal warning – becomes contested, even upended.

Witness the remarks of Steve Bannon, chief strategist in Donald Trump’s White House and the former chairman of the far-right Breitbart website. In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Bannon promised that the Trump era would be “as exciting as the 1930s”. (In the same interview, he said “Darkness is good” – citing Satan, Darth Vader and Dick Cheney as examples.)

“Exciting” is not how the 1930s are usually remembered, but Bannon did not choose his words by accident. He is widely credited with the authorship of Trump’s inaugural address, which twice used the slogan “America first”. That phrase has long been off-limits in US discourse, because it was the name of the movement – packed with nativists and antisemites, and personified by the celebrity aviator Charles Lindbergh – that sought to keep the US out of the war against Nazi Germany and to make an accommodation with Hitler. Bannon, who considers himself a student of history, will be fully aware of that 1930s association – but embraced it anyway.

That makes him an outlier in the US, but one with powerful allies beyond America’s shores. Timothy Snyder, professor of history at Yale and the author of On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, notes that European nationalists are also keen to overturn the previously consensual view of the 30s as a period of shame, never to be repeated. Snyder mentions Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán, who avowedly seeks the creation of an “illiberal” state, and who, says Snyder, “looks fondly on that period as one of healthy national consciousness”.

The more arresting example is, perhaps inevitably, Vladimir Putin. Snyder notes Putin’s energetic rehabilitation of Ivan Ilyin, a philosopher of Russian fascism influential eight decades ago. Putin has exhumed Ilyin both metaphorically and literally, digging up and moving his remains from Switzerland to Russia.

Among other things, Ilyin wrote that individuality was evil; that the “variety of human beings” represented a failure of God to complete creation; that what mattered was not individual people but the “living totality” of the nation; that Hitler and Mussolini were exemplary leaders who were saving Europe by dissolving democracy; and that fascist holy Russia ought to be governed by a “national dictator”. Ilyin spent the 30s exiled from the Soviet Union, but Putin has brought him back, quoting him in his speeches and laying flowers on his grave.

Still, Putin, Orbán and Bannon apart, when most people compare the current situation to that of the 1930s, they don’t mean it as a compliment. And the parallel has felt irresistible, so that when Trump first imposed his travel ban, for example, the instant comparison was with the door being closed to refugees from Nazi Germany in the 30s. (Theresa May was on the receiving end of the same comparison when she quietly closed off the Dubs route to child refugees from Syria.)

When Trump attacked the media as purveyors of “fake news”, the ready parallel was Hitler’s slamming of the newspapers as the Lügenpresse, the lying press (a term used by today’s German far right). When the Daily Mail branded a panel of high court judges “enemies of the people”, for their ruling that parliament needed to be consulted on Brexit, those who were outraged by the phrase turned to their collected works of European history, looking for the chapters on the 1930s.

The Great Depression

So the reflex is well-honed. But is it sound? Does any comparison of today and the 1930s hold up?

The starting point is surely economic, not least because the one thing everyone knows about the 30s – and which is common to both the US and European experiences of that decade – is the Great Depression. The current convulsions can be traced back to the crash of 2008, but the impact of that event and the shock that defined the 30s are not an even match. When discussing our own time, Krugman speaks instead of the Great Recession: a huge and shaping event, but one whose impact – measured, for example, in terms of mass unemployment – is not on the same scale. US joblessness reached 25% in the 1930s; even in the depths of 2009 it never broke the 10% barrier.

The political sphere reveals another mismatch between then and now. The 30s were characterised by ultra-nationalist and fascist movements seizing power in leading nations: Germany, Italy and Spain most obviously. The world is waiting nervously for the result of France’s presidential election in May: victory for Marine Le Pen would be seized on as the clearest proof yet that the spirit of the 30s is resurgent.

There is similar apprehension that Geert Wilders – who speaks of ridding the country of “Moroccan scum” – has led the polls ahead of Holland’s general election on Wednesday. And plenty of liberals will be perfectly content for the Christian Democrat Angela Merkel to prevail over her Social Democratic rival, Martin Schulz, just so long as the far-right Alternative für Deutschland makes no ground. Still, so far and as things stand, in Europe only Hungary and Poland have governments that seem doctrinally akin to those that flourished in the 30s.

That leaves the US, which dodged the bullet of fascistic rule in the 30s – although at times the success of the America First movement, which at its peak could count on more than 800,000 paid-up members, suggested such an outcome was far from impossible. (Hence the intended irony in the title of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel, It Can’t Happen Here.)

Donald Trump has certainly had Americans reaching for their history textbooks, fearful that his admiration for strongmen, his contempt for restraints on executive authority, and his demonisation of minorities and foreigners means he marches in step with the demagogues of the 30s.

But even those most anxious about Trump still focus on the form the new presidency could take rather than the one it is already taking. David Frum, a speechwriter to George W Bush, wrote a much-noticed essay for the Atlantic titled, “How to build an autocracy”. It was billed as setting out “the playbook Donald Trump could use to set the country down a path towards illiberalism”. He was not arguing that Trump had already embarked on that route, just that he could (so long as the media came to heel and the public grew weary and worn down, shrugging in the face of obvious lies and persuaded that greater security was worth the price of lost freedoms).

Similarly, Trump has unloaded rhetorically on the free press – castigating them, Mail-style, as “enemies of the people” – but he has not closed down any newspapers. He meted out the same treatment via Twitter to a court that blocked his travel ban, rounding on the “so-called judge” – but he did eventually succumb to the courts’ verdict and withdrew his original executive order. He did not have the dissenting judges sacked or imprisoned; he has not moved to register or intern every Muslim citizen in the US; he has not suggested they wear identifying symbols.

These are crumbs of comfort; they are not intended to minimise the real danger Trump represents to the fundamental norms that underpin liberal democracy. Rather, the point is that we have not reached the 1930s yet. Those sounding the alarm are suggesting only that we may be travelling in that direction – which is bad enough.

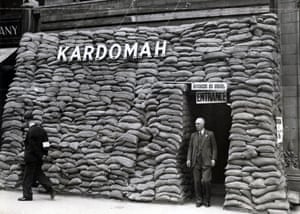

Two further contrasts between now and the 1930s, one from each end of the sociological spectrum, are instructive. First, and particularly relevant to the US, is to ask: who is on the streets? In the 30s, much of the conflict was played out at ground level, with marchers and quasi-military forces duelling for control. The clashes of the Brownshirts with communists and socialists played a crucial part in the rise of the Nazis. (A turning point in the defeat of Oswald Mosley, Britain’s own little Hitler, came with his humbling in London’s East End, at the 1936 battle of Cable Street.)

But those taking to the streets today – so far – have tended to be opponents of the lurch towards extreme nationalism. In the US, anti-Trump movements – styling themselves, in a conscious nod to the 1930s, as “the resistance” – have filled city squares and plazas. The Women’s March led the way on the first day of the Trump presidency; then those protesters and others flocked to airports in huge numbers a week later, to obstruct the refugee ban. Those demonstrations have continued, and they supply an important contrast with 80 years ago. Back then, it was the fascists who were out first – and in force.

Snyder notes another key difference. “In the 1930s, all the stylish people were fascists: the film critics, the poets and so on.” He is speaking chiefly about Germany and Italy, and doubtless exaggerates to make his point, but he is right that today “most cultural figures tend to be against”. There are exceptions – Le Pen has her celebrity admirers, but Snyder speaks accurately when he says that now, in contrast with the 30s, there are “few who see fascism as a creative cultural force”.

Fear and loathing

So much for where the lines between then and now diverge. Where do they run in parallel?

The exercise is made complicated by the fact that ultra-nationalists are, so far, largely out of power where they ruled in the 30s – namely, Europe – and in power in the place where they were shut out in that decade, namely the US. It means that Trump has to be compared either to US movements that were strong but ultimately defeated, such as the America First Committee, or to those US figures who never governed on the national stage.

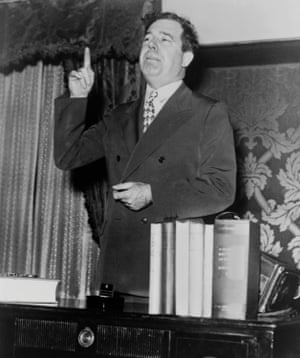

In that category stands Huey Long, the Louisiana strongmanwho ruled that state as a personal fiefdom (and who was widely seen as the inspiration for the White House dictator at the heart of the Lewis novel).

“He was immensely popular,” says Tony Badger, former professor of American history at the University of Cambridge. Long would engage in the personal abuse of his opponents, often deploying colourful language aimed at mocking their physical characteristics. The judges were a frequent Long target, to the extent that he hounded one out of office – with fateful consequences.

Long went over the heads of the hated press, communicating directly with the voters via a medium he could control completely. In Trump’s day, that is Twitter, but for Long it was the establishment of his own newspaper, the Louisiana Progress (later the American Progress) – which Long had delivered via the state’s highway patrol and which he commanded be printed on rough paper, so that, says Badger, “his constituents could use it in the toilet”.

All this was tolerated by Long’s devotees because they lapped up his message of economic populism, captured by the slogan: “Share Our Wealth”. Tellingly, that resonated not with the very poorest – who tended to vote for Roosevelt, just as those earning below $50,000 voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 – but with “the men who had jobs or had just lost them, whose wages had eroded and who felt they had lost out and been left behind”. That description of Badger’s could apply just as well to the demographic that today sees Trump as its champion.

Long never made it to the White House. In 1935, one month after announcing his bid for the presidency, he was assassinated, shot by the son-in-law of the judge Long had sought to remove from the bench. It’s a useful reminder that, no matter how hate-filled and divided we consider US politics now, the 30s were full of their own fear and loathing.

“I welcome their hatred,” Roosevelt would say of his opponents on the right. Nativist xenophobia was intense, even if most immigration had come to a halt with legislation passed in the previous decade. Catholics from eastern Europe were the target of much of that suspicion, while Lindbergh and the America Firsters played on enduring antisemitism.

This, remember, was in the midst of the Great Depression, when one in four US workers was out of a job. And surely this is the crucial distinction between then and now, between the Long phenomenon and Trump. As Badger summarises: “There was a real crisis then, whereas Trump’s is manufactured.”

And yet, scholars of the period are still hearing the insistent beep of their early warning systems. An immediate point of connection is globalisation, which is less novel than we might think. For Snyder, the 30s marked the collapse of the first globalisation, defined as an era in which a nation’s wealth becomes ever more dependent on exports. That pattern had been growing steadily more entrenched since the 1870s (just as the second globalisation took wing in the 1970s). Then, as now, it had spawned a corresponding ideology – a faith in liberal free trade as a global panacea – with, perhaps, the English philosopher Herbert Spencer in the role of the End of History essayist Francis Fukuyama. By the 1930s, and thanks to the Depression, that faith in globalisation’s ability to spread the wealth evenly had shattered. This time around, disillusionment has come a decade or so ahead of schedule.

The second loud alarm is clearly heard in the hostility to those deemed outsiders. Of course, the designated alien changes from generation to generation, but the impulse is the same: to see the family next door not as neighbours but as agents of some heinous worldwide scheme, designed to deprive you of peace, prosperity or what is rightfully yours. In 30s Europe, that was Jews. In 30s America, it was eastern Europeans and Jews. In today’s Europe, it’s Muslims. In America, it’s Muslims and Mexicans (with a nod from the so-called alt-right towards Jews). Then and now, the pattern is the same: an attempt to refashion the pain inflicted by globalisation and its discontents as the wilful act of a hated group of individuals. No need to grasp difficult, abstract questions of economic policy. We just need to banish that lot, over there.

The third warning sign, and it’s a necessary companion of the second, is a growing impatience with the rule of law and with democracy. “In the 1930s, many, perhaps even most, educated people had reached the conclusion that democracy was a spent force,” says Snyder. There were plenty of socialist intellectuals ready to profess their admiration for the efficiency of Soviet industrialisation under Stalin, just as rightwing thinkers were impressed by Hitler’s capacity for state action. In our own time, that generational plunge in the numbers regarding democracy as “essential” suggests a troubling echo.

Today’s European nationalists exhibit a similar impatience, especially with the rule of law: think of the Brexiters’ insistence that nothing can be allowed to impede “the will of the people”. As for Trump, it’s striking how very rarely he mentions democracy, still less praises it. “I alone can fix it” is his doctrine – the creed of the autocrat.

The geopolitical equivalent is a departure from, or even contempt for, the international rules-based system that has held since 1945 – in which trade, borders and the seas are loosely and imperfectly policed by multilateral institutions such as the UN, the EU and the World Trade Organisation. Admittedly, the international system was weaker to start with in the 30s, but it lay in pieces by the decade’s end: both Hitler and Stalin decided that the global rules no longer applied to them, that they could break them with impunity and get on with the business of empire-building.

If there’s a common thread linking 21st-century European nationalists to each other and to Trump, it is a similar, shared contempt for the structures that have bound together, and restrained, the principal world powers since the last war. Naturally, Le Pen and Wilders want to follow the Brexit lead and leave, or else break up, the EU. And, no less naturally, Trump supports them – as well as regarding Nato as “obsolete” and the UN as an encumbrance to US power (even if his subordinates rush to foreign capitals to say the opposite).

For historians of the period, the 1930s are always worthy of study because the decade proves that systems – including democratic republics – which had seemed solid and robust can collapse. That fate is possible, even in advanced, sophisticated societies. The warning never gets old.

But when we contemplate our forebears from eight decades ago, we should recall one crucial advantage we have over them. We have what they lacked. We have the memory of the 1930s. We can learn the period’s lessons and avoid its mistakes. Of course, cheap comparisons coarsen our collective conversation. But having a keen ear tuned to the echoes of a past that brought such horror? That is not just our right. It is surely our duty.

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/11/1930s-humanity-darkest-bloodiest-hour-paying-attention-second-world-war?CMP=share_btn_tw&wpmm=1&wpisrc=nl_todayworld