Carnegie Europe is on the ground at the 2020 Munich Security Conference, offering readers exclusive access to the debates as they unfold and providing insights on today’s threats to international peace and stability.

***

The number of leaders and ministers who took to the podium during the second day of the Munich Security Conference (MSC) was impressive.

And for several reasons.

They all had to answer (sort of) if there was a state of “Westlessness.” However, although some of them circumvented this tricky description of the West, the consensus was that the West was (sort of) coping, provided its leaders had the political will.

The president of France, Emmanuel Macron, wants Europe to have that political will, which he believes is currently lacking.

In often passionate and eloquent replies during a conversation with the MSC chairman, Wolfgang Ischinger, Macron pulled no punches. He wants a much more integrated “core” Europe that would push Europe forward, and if other EU member states want to join, that’s fine. Macron is also no great fan of further EU enlargement until the EU decides its future direction and redefines the terms of further expansion.

As for Russia, he’s not entirely convincing. Macron has now several times repeated that Russia has moved closer to China because of its poor relations with Europe and the EU’s continuing sanctions policy, which started after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014.

His argument is that if only Russia didn’t feel so alienated, and if the EU had a strategy toward the country, things would be better.

That’s not good enough when it comes to explaining Moscow’s relations with Beijing. There are solid, realpolitik reasons for this relationship: Russia wants China for peace on its eastern border, and China “embraces” Russia to keep it from falling into the ambit of the United States, China’s main competitor. But that’s a topic for another blog.

German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, who has the unenviable task of heading a ministry that is painfully slow to modernize and shockingly bureaucratic, didn’t pull punches about the West either.

“[The West] is being challenged in very specific and concrete terms,” she said, mentioning the annexation of Crimea, Islamist terrorism, war in Syria, nuclear proliferation, and territorial disputes in the Indo-Pacific.

“Those who oppose the Western idea have the will to act and to use military forces,” she added.

“The opponents of Western ideas are creating new realities, sometimes brutally and ruthlessly. What is the West doing? . . . We are dwelling on our weaknesses. We have plenty to say about the actions of others. And we complain,” said Kramp-Karrenbauer. “I fully agree with Emmanuel Macron. . . . We should take concrete action together to improve our security.”

“I firmly believe that we can preserve and consolidate the liberal international order and the West.”

Great intentions.

But, and this is the second point, what all the speakers omitted—regardless of what country they came from—was the impact of technology and digitalization. Both are radically changing how democracies function, how they are manipulated, how authoritarian states and nonstate actors use them to disrupt.

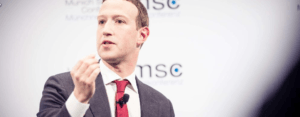

That was why it was interesting to hear Mark Zuckerberg, CEO and founder of Facebook, explain how his company is waking up—finally—to the fact that it has been used by actors to weaken the democratic system and how Facebook is now dealing with that.

“We were slow to understand the information operation that Russia and others were running online,” he said, referring to outside interference in the Brexit referendum and the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

He was speaking during an all-too-short Q&A session on the MSC podium—and facing a largely European audience, highly skeptical of Zuckerberg’s commitment to curb the disruptive impact of Facebook on democratic institutions and processes. He tried to win them over.

Zuckerberg said that, since 2016, Facebook has played an increasing role in protecting the integrity of elections.

“Last year, we took down fifty coordinated information operations . . . including one coming out of Russia in Ukraine and one out of Iran that was targeting the U.S.,” he said. “We take down more than a million fake accounts a day.”

This interference, as is well-known, is not only foreign, but increasingly domestic too.

“Actors are getting more sophisticated in trying to hide their tracks. . . . We have 30,000 people at Facebook working on content and security review,” Zuckerberg said. “But we have to stay vigilant. This is definitely an area where there will continue to be threats.”

Few would dispute that.

And that is the threat facing the West. If it wants to protect its democratic systems, it has to come up with ways to find the balance between regulating all the aspects of digitalization—including social media—and protecting its democratic institutions.

None of the speakers in the main hall of the Hotel Bayerischer Hof addressed these issues. But it is digitalization that’s driving the pressures—positive and negative—on democracies and on authoritarian regimes. That is why the idea of “Westlessness,” if it even exists, has to take into account the new phenomena of the twenty-first century.

And this is the third point.

All the speakers on the MSC’s second day, regardless of where they came from, used conventional, late-twentieth-century language to describe the challenges facing the West today.

But those challenges are about harnessing technology and digitalization. China, Russia, Egypt, Turkey, to name just a few countries, are doing it for their own purposes. In order to support its own values, why can’t the West do it too?

By the way, Zuckerberg, unless I am mistaken, didn’t mention the West at all.

Photo credit: MSC/Kuhlmann