Chinese President Xi Jinping embarked on his first trip outside China’s borders since January 2020 on Wednesday, beginning in Kazakhstan and then traveling to Uzbekistan for a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit. Once a frequent global traveler, Xi has not left China since a visit to Myanmar shortly before Beijing began locking down the country in response to the novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. The leader had even avoided Hong Kong until June.

The trip to Central Asia was confirmed earlier this week, putting an end to previous claims that Saudi Arabia or Southeast Asia would be Xi’s first overseas destination. His transformation into a homebody seems prompted by a mixture of concerns over both COVID-19 and China’s domestic political situation.

In the early days of the pandemic, Xi and other top political leaders were kept behind a COVID-19 cordon, and Beijing has had some of the toughest quarantine rules in China. But anxiety about power struggles at home also may have played a role in Xi’s plans, with the president unwilling to leave the country out of fear of rivals moving against him. China’s multiple crises—from the ongoing constraints of the zero-COVID policy to a stagnating economy—likely made Xi’s fears more acute.

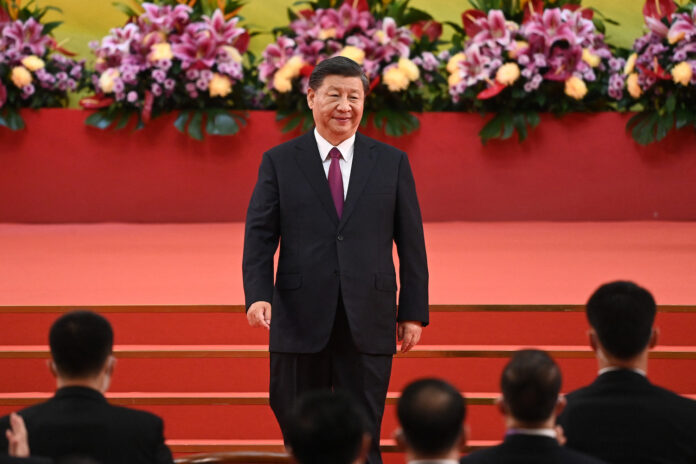

The current trip, then, signals strong confidence ahead of the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that opens on Oct. 16, when Xi will almost certainly confirm his third term as leader after changing the constitution in 2018 and breaking with the precedent of his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

The SCO summit will also see Xi meet Russian President Vladimir Putin for the second time this year. At the Beijing Winter Olympics in February—just before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—the two leaders pledged a “no limits” friendship between Russia and China. Although China has not officially endorsed the invasion and maintains diplomatic relations with Ukraine, its official and media rhetoric is pro-Russian, and opposing voices have been censored within China.

On a visit to Russia ahead of Xi’s trip, third-ranking Chinese leader Li Zhanshu praised Russia’s “important choice” under supposed threat from NATO, which tracks with Chinese propaganda. At the same time, Chinese institutions have largely cooperated with sanctions on Russia, even as the government has condemned them. There is little sign of the Chinese materiel support for the war that some analysts feared. Amid Russia’s recent military setbacks, Xi’s conversation with Putin may be somewhat strained—although still accompanied by shared anti-Western feeling.

Yet the SCO summit is more about building China’s close ties with its Central Asian neighbors. Beijing has invested significant time and energy in the region, although it remains more popular with the countries’ leaders than with their publics. The SCO grew in part in reaction to so-called color revolutions in the 2000s, which left Central Asian autocrats fearful and China convinced that the United States was behind every plot. (It’s difficult to know how much of such claims is propaganda versus sincere belief, but my private conversations with Chinese officials suggest the conviction is largely sincere.)

One of the main components of the SCO is joint military exercises, known as “peace missions”—supposedly counterterrorism exercises—which in practice look like rehearsals for suppressing popular revolt with foreign military force, as Russia did in Kazakhstan in January. Although Central Asia’s autocrats might want a Russian or Chinese guarantee of their power, this tactic raises fear with the public, who see the arrival of foreign military forces as a threat of new imperialism.

But Xi’s Kazakhstan trip has already delivered an implicit check on Russia’s imperial ambitions, with Xi promising that “no matter how the international situation changes, we will continue to resolutely support Kazakhstan.” Despite Russia’s aid this year, Kazakhstan has effectively supported Ukraine in the war, refusing to condone the invasion and largely allowing strong public condemnations of Russia. That has prompted anger from Russian nationalists, who have suggested that Kazakhstan should be next—and a quickly deleted post from Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy chairman of Russia’s Security Council, questioning Kazakhstan’s sovereignty.

It’s unlikely that an exhausted and overstretched Russia would make any serious threat against Kazakhstan—but Xi’s words may be welcome in a region that is used to playing great powers against each other.