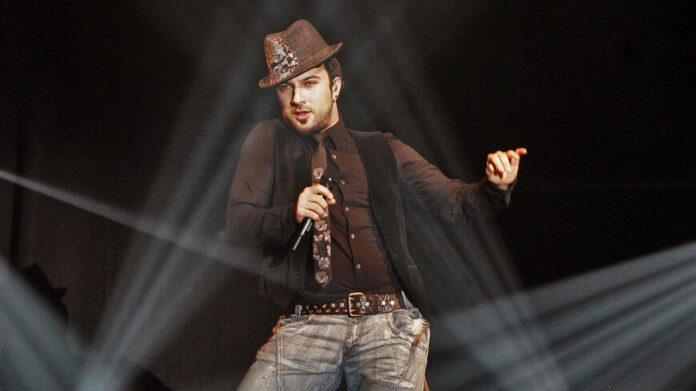

IZMIR, Turkey — “I am not going anywhere until he sings ‘Geccek,’” Ayda Gurel, a 20-year-old student at one of Izmir’s private universities, said as she elbowed her way further to the stage where Turkish pop star Tarkan sang and danced on Sept. 9.

The megastar’s concert, which drew hundreds of thousands to Izmir’s waterfront, was the key event at the centennial celebrations that marked the port city’s “liberation” by Mustafa Kemal’s forces after three years of Greek occupation after the First World War. Many Turks see the recapturing of the multicultural trade city as one of the building blocks of the modern republic founded by Kemal Ataturk in 1923.

But in Turkey, where everything from dogs to dead poets can be a source of polarization, the concert and the celebration also showed the country’s divisions. Even before Tarkan sang the final song of the concert — the politically charged “Geccek” (“It Will Pass”) — the battle lines between the opposition vs. the government, Neo-Ottomans vs. Kemalists and nationalists vs. members of minorities had already been drawn.

The biggest fire of attack was when Soyer, in his opening remarks, drew an analogy between the current Justice and Development (AKP) government and the Ottoman sultans of the early 20th century.

“A hundred years ago, those who ruled the country were misguided and even treacherous,” Soyer said, using a quote from Ataturk’s speech to the Turkish youth in a thinly veiled reference to Erdogan who is often called “The Sultan” in media. “They did not have a single thought for the people of the country as they put a whole nation into the fire to keep their lavish life in the Palace.”

AKP spokesperson Omer Celik criticized Soyer for painting the Ottoman Empire as the enemy instead of Greece against whose forces Kemal’s army fought as the occasion demanded. Devlet Bahceli, the nationalist ally of the AKP, accused Soyer of “failing to utter a single word to those who invaded the country with their bloody boots” but instead attacking the Ottoman forefathers of the nation. Samil Tayyar, a pro-Erdogan pundit and former politician, called Soyer “the mayor of Athens,” adding, “Clearly, we have not thrown all the Greek traitors to the sea. … The seeds of those traitors are now walking among us, insulting the forefathers and sons of this land.”

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the most powerful advocate of the country’s Ottoman heritage, stepped into the fray Monday as he addressed the first day of the school year, urging students not to lend an ear to “those who insult their own ancestors.”

Soyer defended himself Monday morning on the grounds that he had simply quoted Ataturk, the hero of the war of independence, and clearly said in his speech that the victory had been against imperialist forces — France, the UK, Italy and Greece — who attempted to carve up the Ottoman Empire with the Treaty of Sevres in 1920.

Tarkan also came under attack by the pro-government pundits for consenting to be the star of an event staged by a city known for its opposition to the government. “Tarkan, who is the undisputed king of pop, has started to be the voice of a single lifestyle,” wrote Ahmet Hakan, the chief columnist of pro-government Hurriyet. “He has become overtly drawn to the everyday struggles of politics.”

Tarkan, a 49-year-old born of Turkish parents in Germany, has been topping music charts since the 1990s, paring colloquialism in lyrics with catchy tunes. Older people love his clean-cut image and ability to sing classical Turkish songs; the youth admire his dance and bold body movements, as well as his androgynous image. The king of pop also shows good political conscience — he became increasingly political. He campaigned to stop the destruction of Hasankeyf with the song “Uyan” (“Wake Up”), supported anti-nuke demonstrations and unabashedly stood by Gulsen, the popstar facing court for insulting religion.

Tarkan faced attacks from government circles earlier this year when he swept into national and international headlines with his last hit, “Geccek” (“It Will Pass”), which has become the march of those who wanted to see the end of the 20-year AKP rule. “This shall pass, you’ll see, you’ll be recharged, we’ll dance a jig then, beautiful days are coming,” went the lyrics. Opposition politicians tweeted the clip. Tarkan refused to be drawn into a political debate, saying he wrote it because he was feeling tired and frustrated with the COVID-19 restrictions.

Besides criticism from government circles about the centennial concert, another debate surfaced on the skeletons in Izmir’s closet during the liberation. “You started as revolutionaries, you ended up White Turks (name for bourgeoise, entitled Turkish people). So go ahead and enjoy yourself tonight, bravo,” tweeted journalist Alin Ozinian, which was followed by a fierce debate on atrocities committed in Izmir by Turkish “chetes,” or unruly militae, after Turkish forces captured the city. Many opposed the criticism, saying that given the AKP’s restrictions on music, the concert was a political act that should be enjoyed rather than criticized.

Izmir, currently known as the bastion of liberalism in Turkey, has many unspoken wounds. In 1922, by the time Kemal’s forces entered the city after a decisive victory 90 kilometers away from the city, many of the Greek soldiers had already left in most of the military vessels, leaving behind Greeks and Armenians at the ports. Days of hunger, pillage, looting, raping and killing were followed by the Great Fire of Smyrna — possibly several fires in different parts of town — burning half of the city to the ground, mainly the Greek and Armenian parts. A hundred years after what Turks call liberation and the Greeks call “catastrophe,” Turks, Greeks and Armenians still have fierce debates on who started the fire. Ataturk, who watched the city go down in flames from the balcony of his hostess (and later, wife) Latife Usakligil, assured her that the city would be rebuilt. The new Izmir, however, was but a pale shadow of its multicultural past when Greek, Italian, French, Ladino and Armenian were spoken simultaneously on the streets.

Western historians — such as Philip Mansel, author of “Levant: Splendor and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean,” and Giles Milton, author of “Paradise Lost” — maintain that many non-Turkish eyewitnesses say that the fire was started by Turkish soldiers.

“There are many conflicting views and mutual accusations on who started the fire of Izmir,” Bulent Senocak, author and publisher of the Turkish translation of Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” told Al-Monitor. “Armenian and Greek sources claim that it was the Turkish soldiers, and Turkish sources blame the Greeks and the Armenians. I personally do not think that it makes sense for the Turkish soldiers to burn down a city they have already captured — a view that is shared by some French and American sources. The starting of the fire by the Greek military, on the other hand, does not make much sense either. Most of them had already fled the city on Sept. 8, and the few that remained were in hiding and far too feeble to carry out an arson attack. I think the most likely culprit is the Armenian gangs who were armed. But I also think that it is a mistake to place the blame of the gangs on ‘Armenians’ as a whole.”

Tarkan, a master of communications, sent a message focusing on unity rather than divisions after the concert. “What I have seen [on the night of Sept. 9] was hundreds of thousands of people embracing each other with love and having fun. We missed that solidarity, this absence of division and polarization,” he tweeted. “We missed beating as a single heart — without pressure, without bans — and celebrating our differences.”