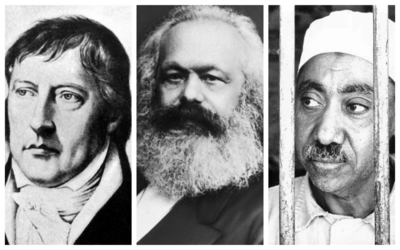

| Mansour: “Theology made philosophy by Hegel [l], philosophy made politics by Marx [c], and then politics was made into a religion. So naturally, Qutb’s [r] . . . conversion of the Marxist inversion reverted back into theology.” |

After the Great War, Arab societies, like many others, for the first time came to know politics as a modern mass phenomenon in which modern communication technologies are used for mass political mobilization. For the first time, intellectuals, journalists, poets, and men of letters of all sorts replaced the old classes of religious scholars by becoming the source of moral knowledge and ethical education for the public. The new trend of inspiring people with a total philosophical “vision,” the conversion of artistic sensibilities into populist political symbols, and the pooling of mass support into a demand, symbol, or figure that could be converted to power became the mainstays of Levantine and Egyptian politics. At the heart of this new trend were the two most transformative revolutionary ideologies German philosophy has produced: romantic nationalism and Marxism, and their struggle against the common postwar enemy of Western imperialism.

Nationalism as a romanticist literary and artistic phenomenon could be discerned in late-19th-century Arabic writing and art, yet it was not until the interwar years that nationalism mattered as a mobilizing revolutionary impulse around which political movements could form and as a literary genre of romantic imagination. The revolutionary impulse that started to ferment during the Great War and accelerated after its end was a generally anti-imperialist fervor without ideological content or clear direction. It is best to imagine it as a primordial pool to which intellectual and political developments in Europe, such as Marxist-Leninism, fascism, Nazism, and antisemitism constantly flowed, and from which the political movements that shaped the region today emerged.

Arab nationalism was the first and earliest idea which articulated a cohesive ideology for the region in the works of its intellectual father, Sati Al-Husri (1880-1968). A former Ottoman officer, Husri became one of the first modern Arab educators for whom education meant the mission of preparing and producing nationalist youth and endowing it with a Prussian militant sense of historical mission. The idea that the Hegelian conception of the political community as a historical protagonist whose members form an organic unity with a transcendent salvific mission inside history could find its inevitable realization only in the establishment of a state. The outright rejection and delegitimation of current reality in favor of a supposedly historically inevitable future which is the only legitimate reality possible is a prerequisite of Hegelian revolutionary action. Those who defend the present naturally become an obstacle and enemies of history itself.

Constricting the idea of natural political legitimacy, in itself a modern philosophical concept, to a political reality that must be identical to an abstract and ideal notion of a great Arab or Islamic nation, embodying a certain mystical essence, naturally led to complete delegitimation of any political reality short of such ideal while establishing legitimacy, and not sovereignty, as the criterion of political truth. Actual, lesser nation-states were delegitimated as “artificial” products of European colonialism, a view enshrined in the fictitious and ideological treatment of historical episodes such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Such philosophical conception can be clearly grasped in all modern Middle Eastern political ideologies; it can be discerned, for instance, in the Baathist slogan, “One Arab nation with an eternal mission,” or in that of the Muslim Brotherhood, “Islam is the solution,” or in the propaganda of ISIS which named the video of its deceleration as “The End of Sykes-Picot.”

As Hegelianism and its ideologies were shaping Arab thought, a new generation of men of letters emerged, primarily in Egypt and the Levant, whose work valorized self-expression, the quest for authenticity, romantic ideals, and artistic subjectivity as a sense of mystical duty toward some absolute spirit. The sense of romantic struggle provided a literary fantastic view of a heroic self, encircled by a world of hostile forces; seeking to overcome such a world by unlocking the authenticity of one’s most inner self naturally intersected with a new kind of political activism centered on deeply mystical notions of nature, blood, soil, liberation, death, regenerative violence, and armed struggle. European phenomena such as cultural salons, secret societies, and militant youth groups led by intellectuals, self-identifying as vanguards, with unique colored shirts and carrying slogans referring to death, iron, and fire proliferated.

It was therefore inevitable that such intellectual and psychological conditions would lead to consequences not too dissimilar from the consequences of such conditions in Europe; the appearance of popular political movements carrying devotional romantic symbols founded by self-styled fuehrers who embodied the potent Leninist mix of intellectual-politicians leading a vanguard in the final phase of a historical struggle toward an inevitable salvific future in which all contradictions will be resolved. In the interwar years in Egypt and the Levant, communist, Arabist, Egyptianist, Syrianist, and Islamist groups proliferated and created an ideologically competitive mimetic contagion. Together, those groups formed a common space where the abstract ideas of German philosophy, nationalism, socialism, unification and European revolutionary thought combined and recombined along with the local symbols of Islam and Arab culture and altered the entire substructure of Arab thought.

If the arrival of the Arabic printing press in the 19th century allowed literary nationalism and romanticist ideas to proliferate among the new educated classes, the shortwave radio brought a new phase of possibilities carrying on its waves the thunderous voices of mass mobilization. The new possibilities of the new technologies were first fully realized in the Middle East by the two protagonists of the global European revolution known as WWII, Italy and Germany. The former established its Arabic Radio Bari station in 1934 and the latter, the Voice of Berlin in Arabic, in 1939. Together, they filled the airwaves with Arabic propaganda of the most sensationalist kind mixing Islamic motifs and symbols with anti-Westernism, antisemitism, and incitement to mass violence. Radio Bari and the Voice of Berlin championed the national liberation of all the Arab and Muslim peoples and warned against the conspiracies of imperialist powers and the “Jewish States of America,” and called for a revolution against the West.

Many of the antisemitic catchphrases and conspiracy theories still found in Arabic culture today can indeed be traced to the legacy of the Voice of Berlin and its Iraqi anchor, Yunis Bahri. According to the British propaganda official, Nevill Barbour, “The Nazis had the skill or luck to find and employ an Iraqi, Yunus al-Bahri, who had a remarkable talent for the sensational type of broadcasting which they favored. Berlin Radio was bound by no scruples and cared nothing for factual accuracy … it, therefore, used every device to inflame Arab resentment against Britain for favoring Zionism, to exploit every conceivable suspicion regarding British actions, and to sneer at Arabs who publicly declared their support of the British connection. The Berlin Radio announcer, for instance, used regularly to refer to Prince Abdallah as ‘Rabbi Abdallah.'”

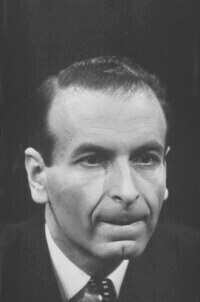

Abdulrahman Badawi, “the first modern Arab philosopher … show[ed] deep sympathies with Germany and Nazism and a near-pathological obsession with Jews.” Abdulrahman Badawi, “the first modern Arab philosopher … show[ed] deep sympathies with Germany and Nazism and a near-pathological obsession with Jews.” |

Nazism and fascism served as an inspiration and a prototype to many aspiring movements such as the Syrian Socialist National Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. The excitement in the prospects of a German victory brought, along with Arab intellectual affections to German philosophy, can be clearly read in almost all the memoirs of those who came to political age during the period including Presidents Nasser and Sadat in Egypt and Antun Saadah in Syria. More significant than politicians, in my opinion, are those who would become the founders of Arab and Muslim modern thought, such as the Egyptian thinker Abdulrahman Badawi, the first modern Arab philosopher, a figure of utmost importance, whose memoirs show deep sympathies with Germany and Nazism and a near-pathological obsession with Jews. Or the most prominent Algerian thinker of the era of national liberation, Malek Bennabi, who was accused later by France of having been a Nazi collaborator.

During the war, the minority of Arab intellectuals and thinkers who firmly opposed Nazism and fascism belonged to either the older generations of the pro-British or else were young communists. Otherwise, it is not an exaggeration to say that the overwhelming majority sympathized with Germany and the Axis and encouraged the population to do so. The political fervor of the time was primarily anti-British, anti-French, and anti-Jewish, and in favor of revolutionary mobilization; the question of ideology was secondary at best. That is why qualifiers of ideological identity added to famous figures of the period, such as Haj Amin el-Husseini, often oscillate between describing him as an Arab nationalist and or as an Islamist.

By the end of the 1940s and as the Cold War started, the atmosphere of struggle had permeated the minds of the most modern Arab societies and they were ripe for the beginning of their revolution. In retrospect, it seems only fitting that the end of the colonial era in the Middle East was ushered by a sequence of events that was the culmination of the story outlined above and the foreshadowing of the decades to come; the first Arab-Israeli war of 1948 and the mass expulsion of Jews from Arab ruled lands, the coup d’etat in Syria in 1949, and the coup d’etat in Egypt in 1952.

The revolutionary wave which has been fermenting for decades in the primordial soup of revolutionary ideas burst forth as the sun was setting on European colonialism to carry the mission of national liberation and decolonization in Egypt, Syria, Algeria, and Iraq. The revolutionary milieu which oversaw the establishment of the Syrian Republic included Baathists, Syrian nationalists, proto-Islamists, and communists. Similarly, the 1952 coup in Egypt followed by the rise of Nasserism, was a collective project in which all revolutionaries supported and participated. In other words, the revolutionary wave was the practical embodiment of the primordial pool of ideas mentioned earlier. It formed, in the beginning, a unified revolutionary milieu from which a process of mitosis led to its later fragmentation into the distinct yet interconnected movements of Nasserism, Baathism, Islamism, the Arab new left, and Palestinian nationalism in which the potent mixture of revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary socialism, anti-Westernism, and antisemitism dominated.

One of the prominent members of the revolutionary milieu was none other than Sayyed Qutb, a literary critic who later came to be remembered as the ideological founder of Islamist jihadism. Qutb was part of this revolutionary milieu and an insider in the halls of revolutionary power. His later fallout with Nasser turned him into a kind of a Muslim Gramsci or Trotsky, with which a mixture of revolutionary existentialism, Leninism, and a literary romanticist conception of Islam came to be identified. One way to understand Qutb’s work is to see it with the eyes of a literary critic turned revolutionary, an attempt to extrapolate the literary sensibility of Islam, i.e., divine subjectivity, and use it to existentially shape one’s self in an environment of sensory isolation. Such a process would be followed by the creation of the vanguard which will proceed to realize the spirit of Islam in history.

The revolutions of national liberation led to the establishment of one-party populist states of which Egypt was the largest and most important. The period was that of the euphoric mass sentiment of absolute unity between the people, the state, the heroic leader, and the intellectuals, which was celebrated as true popular democracy. A large public sector, large state investments, and a state-led economy were the essence of Arab socialism. The holy trinity of unity, Arabness, and socialism, the invention of the Baath, became the creed of the new Arab secular political religion. The massive projects of postcolonial modernization, meant heavy investment in literacy programs, free education, and more extensive higher education to produce the needed administrative skills for the new massive state bureaucracies and security apparatus. The confiscation of foreign and Jewish property provided the needed capital for many such projects.

Decolonization and nationalization did not just target industrial assets and land ownership. They also naturally extended to all aspects of cultural life, as the urban cosmopolitanism of the colonial era was to be replaced by a centralized Arab urban culture. In Egypt, the state gradually took control of all educational institutions, secular and religious, all media, print, and radio, record companies, as well as the Egyptian movie industry, which at the time was one of the largest in the world. The progressive Arab left then proceeded to mass radicalize all of society and culture.

Above the reshaping of popular culture, and within the global context of the Cold War, sat a new high Arab culture that was changing its orientation from the fascism and the Nazism that inspired its roots toward Marxism, the Soviet orbit, and specifically the French left, which at the time was wallowing in postwar pessimism that lost hope of revolution in Europe and looked to the former colonies for salvation. By the early 1960s, Jean-Paul Sartre was the most widely read, in-vogue intellectual in the Arabic language, and Arab students and intellectuals found a second home in Parisian cafes. In 1955, Raymond Aron made note of this in his Opium of the Intellectuals and warned the French left against indoctrinating Arab and African young students into ideologies that were not suitable for their societies. Yet the Sartrean combination of valiant existentialism, Marxism, and decolonization along with the French conception of the public intellectual as the lodestar of sacred struggle continued to shape the culture of youth in Cairo, Alexandria, Damasus, Beirut, and Baghdad. His books “sold like bread,” wrote George Tarabishi, one of Sartre’s Arabic translators.

The new generation of revolutionary intellectuals started decolonizing intellectual life by replacing the older generation of men of letters who had dominated under the British and French influence such as Taha Hussein and Abbas Aqqad with politically committed authors. In this, the Arab revolutionary intellectuals were following the steps of the French left who sought to “repudiate the spirit of seriousness” of traditional European philosophy as well as of European bourgeois culture. The Sartrean concept of Commitment was widely enforced, meaning that anyone who wanted to participate in cultural production or public life had to be committed to revolutionary politics. Under the auspices of Commitment, Arabic culture became a culture of struggle. In the autobiographical formula of veteran Lebanese communist Fawaz Taraboulsi, everyone was, “Communist poetically, Arabist politically, Socialist economically, and existentialist philosophically.” If revolutionary romantic heroes were the mimetic contagion of the interwar year, the left-wing existentialist smoking in a cafe, holding a Sartre or a de Beauvoir book, and making pronouncements that are as deeply shallow as they are superficially profound was the mimetic contagion of the ’50s and the ’60s. Literary existentialist feminism, of unprecedented sexual expressionism, appeared in the writings of figures such as Laila Baalbaki and Nazik Al-Malaika.

Suhayl Idris is a case in point. Born in Lebanon in 1925 to a religious Sunni family, Idris proceeded to obtain classical Islamic education in religious law in Beirut. After graduation, he turned secular, obtained a Ph.D. from the French Sorbonne in literature in 1953, and returned to Lebanon to establish the leading Arabic literary periodical and publishing house of the time which translated the works of Sartre, Camus, Isaac Deutscher, Rosa Luxemburg, Gramsci, Marx, and others. Idris’ literary style was the furthest possible from the religious style. In 1956 he wrote, “Today, the Arab writer cannot but put his feather pen in the fountain of the blood of martyrs and heroes … so when he may lift his pen, it drips with the meaning of revolution against imperialism.” And in 1958, objecting to the anti-Soviet, anti-Nasser Baghdad Pact he wrote, “We Arab Nationalists are objecting to the policies of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan despite being Muslim countries … if Islam indeed supported imperialism we would have fought against it!”

Intellectuals with more sophisticated Marxist inclinations had to follow the Soviet line which gave predominance to the revolutionary intersection between the struggle of ruling nationalist petit bourgeois against Western imperialism and the Marxist struggle against capitalism. It encouraged Arab Marxists to focus their analytical works on Western imperialism and not on analyzing the class structure of their own societies. This influence kept Marxism constricted in two areas, polemics against wealthy classes, and a political view of international relations that complemented romantic nationalism.

The Marxist inevitability of revolution and overthrow of Western capitalism created an Arab sense of inevitable triumph against the West and Israel which in turn led to unquestioning support of the revolutionary regimes despite their accumulating record of failures, excesses, abuses, and idiocies. Thus, Arab communists overwhelmingly supported the leadership of Nasser even as they were being tortured in his prisons. A rare exception was the Iraqi Marxist intellectual Ali Al-Wardi, whose sociological studies in Islamic history in the 1950s attempted to provide a historical materialist analysis emphasizing class warfare as the historically meaningful factor in the development of Islamic beliefs.

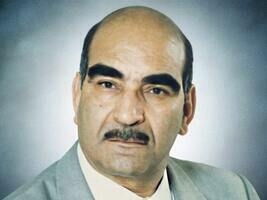

Fayez Sayegh, born in Syria in 1920 to a Presbyterian minister, was the first Arab intellectual to apply Sartre’s critique of racism and neocolonialism to Israel. Fayez Sayegh, born in Syria in 1920 to a Presbyterian minister, was the first Arab intellectual to apply Sartre’s critique of racism and neocolonialism to Israel. |

The ideological developments and transmutations of the periods can be seen in the lives of many figures of the period such as Fayez Sayegh, who was the first Arab intellectual to apply Sartre’s critique of racism and neocolonialism to Israel. He argued that what applies in Congo and Vietnam also applied to Israel, and he was also the principal author of the 1975 U.N. Zionism-is-racism resolution. Sayegh, born in Syria to a Presbyterian minister in 1920, started his active life in the 1940s by joining the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, a Syrian imitation of Nazism under the leadership of the “Fuehrer” Antun Saadeh. During the time Sayegh wrote and spoke for the SSNP about “the danger of Zionism on civilization and the soul,” as well as the dangers of the “Jewish psyche.” After the turn to the left, Sayegh became an Arab existentialist authority on Sartre and Fanon. In 1965, during his tenure at Stanford, he wrote the booklet “Colonialism in Palestine” which was published by the PLO and then translated to a dozen of languages and distributed globally by the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO). His booklet was the birth document of the global cause for Palestine as it hit all the major notes played by the international left—racial supremacy, segregation, exclusion, civil rights, emancipation, anti-capitalism, self-defense, human rights, and resistance—invoked Algeria, African Americans, Congo, and Vietnam, and used existentialist ideas of otherness. It was Sayegh who inserted Palestine into the anti-Western canon of the international left. The later anti-Zionist works by major figures of the French left such as Maxime Rodinson would only continue Sayegh’s work.

The new textbooks, movies, magazines, songs, and literature produced in such an intellectual environment were all tasked with shaping the Arab masses and its new generations ideologically. This was the moment of birth of Arab modernity. Together, the committed new intellectuals and cultural figures produced an entirely committed revolutionary anti-Western and antisemitic reading of Islam. During such a foundational movement of modern Arab mass culture, movies, radio shows, plays, school textbooks, and more enforced and homogenized this new reading of Islamic history, which merged what is gnostic and religious in Hegelian revolutionary thought with what is religious and mystical in Islam. In this new reading, the possibility of transcendence outside history was reworked into the possibility of transcendence inside history through revolution. Salvation was secularized, and atheized, into temporal salvation brought on by a political collective will. That Islam is a philosophical totality to be achieved through national liberation and socialism, and progressive revolution against the forces of colonialism, Judaism (particularly as embodied in Israel), and reaction (embodied in conservative pro-Western Arab monarchies), became the generic message.

For a newly established Arab mass culture, the rewritten career of Muhammad as a revolutionary who came with a message of social justice clashing with a reactionary ruling elite of the Arab bourgeois merchant class and their misanthropic Jewish allies was the foundational historical treatment of Islamic history. Nasser’s minister of propaganda, Fathi Radwan, a former member of the quasi-fascist organization Young Egypt, wrote and distributed the book “Muhammad the Great Revolutionary,” extolling the supposed revolutionary merits of the prophet. The founder of the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, Mustafa al-Siba’i, wrote Socialism in Islam which was printed and mass-distributed by the United Arab Republic in an act of ideological balancing against communists. Historical Muslim figures were lionized and revolutionized in state-produced films with massive budgets. In 1961, the Egyptian state produced the blockbuster film Oh Islam, in which an Egyptian leader of the Arabs is looking for his lost beloved, named Jihad, with which he is able to defeat the Mongol invasion. Another historical epic of medieval Islamic decolonization jihad followed in 1963 in Saladin, a film with a massive budget portraying a proto-Nasser medieval sultan waging secular anti-imperialist jihad against blond and redheaded European colonizers in alliance with reactionary Arab forces.

The new cinematic and literary treatments of Muhammad’s career presented the prophet as a revolutionary leader leading a group of the downtrodden, the oppressed, and the enslaved to resist the capitalism of Mecca’s reactionary merchants and their evil Jewish allies. The pre-Islamic period is portrayed as that of maximum economic exploitation, social corruption, and political chaos. The wealthy, corrupt, and immoral infidel are a feudal class who commissions the local Jews, evil creatures of the night, to do their dark deeds. A dialectical struggle between the two parties, the believers and the infidels, climaxes into the triumph of the Muhammadan revolution and the resolution of all contradictions.

One consequential literary transfusion of such treatment was substituting piety with social justice, substituting religious transcendence with the historical transcendence of a historical stage, and substituting spiritual redemption with socioeconomic and political redemption. However, the most consequential of all substitutions, which will become an insurmountable conceptual foundation in modern Arab culture, is the displacement of the very concept of meaning itself from religion proper and placing it into history. A salvation which meant the total transformation of national political and economic conditions which are in turn assumed to be the human condition. The salvific goal of history substituted an otherworldly salvation that is the goal of God leading to a theological relationship with components of historical movement.

The union between Marxism and Arab nationalism against the enemies of imperialism, reaction, Zionism, and capitalism left its indelible mark on both. Marxism provided the intellectual cohesion and idiom required for any modern political endeavor to be respectable while Arab nationalism provided the medium in which Marxist ideas could be presented to the Arab masses. Arab Marxism also connected Arab nationalism to the dynamic world of Third Worldism but most importantly to the international left, especially in Western capitals and universities, giving it critical prestige, international legitimacy, and an aura of noble-savage romantic heroism. Arab national liberation, decolonization, and the violence that accompanied them, were the empirical verification of the writings of Sartre and Fanon. The gnostic sense of the historical inevitability of the overthrow of capitalism, and the dogmatic faith in holding the final moral truth emboldened an Arab culture with already weak ties to reality to mistake the predictions and prophecies of leftist intellectuals as historical promises, and to sail the ship of Arab dreams ever farther away from the shores of reality, into the ocean of phantasmic self-aggrandizement. A complete belief in the inevitable superiority of the USSR led to betting the future of entire societies on its radical triumph coupled with an adamant denial of Jewish historical reality, seeing Israel only as an ephemeral “Zionist entity” that would soon be blown away into oblivion by the battle cry of the awakened Arab giant.

Yet when the dust settled in 1967 after the sweeping defeat of the forces of Arab nationalism at the hands of Israel, it settled on a transformed landscape. The radical masses intoxicated by the “tall and dark handsome Egyptian” leader and the assured prophecies of intellectuals with superior knowledge had been robbed of their innocence. Narratives of the essential aggrandized self were inverted into narratives of essential victimhood, and the cult of the hero was inverted into a cult of the martyr. Even the direction of the prevalent antisemitism was inverted: Zionism, once seen as merely a ploy in the hands of Western imperialism came to be seen as the original superpower from which all evil flows. The work of the public intellectuals once focused on counting the virtues of the Arab nations and the vices of the West and Israel, turned into that of a professional mourner weeping over the ruins of a lost innocence. Arab culture fell into the self-made trap of solipsism.

The inversion was of such a severe magnitude that the unified culture of the Arab left, in which the state, the people, the culture, the intellectuals, and the leader were perceived as being in a state of ecstatic unity, shattered into fragments, with each going in a different direction. The unity between Arab nationalism and Marxism, which was once asserted by many intellectuals, was dissolved. Nasserism was discredited, Baathism split between Syria and Iraq. The Palestinians started their own revolution inside the revolution. Eventually, the Arab left split into three new circles: The old left, the new left, and the Islamic left leading a revolution against the revolution.

The intellectuals, journalists, and writers who still served the standing pro-Soviet progressive Arab republics came to be generally known as the old Arab left, of which the official intellectual of the Egyptian regime Mohamed Hassanein Heikel was the most famous. The only way this group was to defend the legitimacy of the humiliated states in front of radicalized Arab masses was through the almost endless inflation of their enemies to cosmic proportions that only increased the nobility of their victims. In 1968, Heikel published his first book after the defeat, titled We and America, which portrayed the 1967 war as an American conspiracy to assassinate the young Egyptian revolution. The victimhood escalator ultimately led to ever more pathological antisemitism, a wolfish view of an unforgiving and cruel world, as well as a mystification of victimhood into a sense of cosmic pain so vast as to dissolve any observable reality.

In 1969, the Egyptian state’s largest film production was, Al-Ard (The Land), in which the audience was treated to a final scene where the courageous Egyptian masculine hero, played by superstar Mahmoud Miligy, is standing alone in the middle of his cotton field after being abandoned and betrayed by everyone, sacrificing his life defending his land from a British-feudal conspiracy. He is seen being cut and slashed in slow motion, splashing his blood on the cotton flowers, while a chorus is dramatically chanting in the background, “If the land is ever thirsty, I shall irrigate it with my blood.” This was a major reversal of the pre-1967 production which typically ended in a resounding victory for the hero. If Arab mass culture had no ties to reality before the war, now it had declared war against it.

The Arab new left was made of former Arab nationalist intellectuals and cadres who decided to exit the old left and make a sharper turn to the left. “We were determined to commit to Communism as a final break between ourselves and the nationalist past of the petit bourgeoises,” wrote one intellectual. This coincided with the May 1968 student movements in Europe, the U.S. cultural revolution with its Marxist overtones, and the rise of the global new left which radicalized the global high culture. The first young intellectuals to make this turn were Sadiq Jalal Al-Azm, who in 1968 published his debut book, Self-Criticism After Defeat, and Yasin Al-Hafiz, who published The Defeat and the Defeated Ideology in the same year. Together, Azm and Hafiz would intellectually jump-start the new Arab left and in their new analytical works would imitate the positions of European postwar leftist thought. They rejected Baathism and Nasserism as petit bourgeois ideologies that were as a matter of fact backward-looking, reactionary, and fascist and must be replaced with scientific Marxism.

The post-1967 Arab intellectual life was that of “collective neurosis,” in the words of former Marxist intellectual George Tarabishi. The first self-object of neurotic obsession was Arab culture and Islam. Imitating the Frankfurt School’s analysis which exonerated revolutionary thought from the possibility that it produced Nazism and fascism and instead identified them as manifestations of the latent violence and mythological thinking in European and Christian culture, so did the intellectuals of the new Arab left identify Islam and Arab culture as the source of the region’s own latent reaction and oppression. The 1967 defeat was blamed not on what is gnostic and religious in revolutionary thought, or the Fanonian valorization of brutal violence as a spiritually redemptive act, but on traditional culture. The new leftists doubled down on Marxism and revolutionary thought and placed the entire blame squarely on the irrationalism of traditional culture and religion.

Mohamed Abed Al-Jabiri’s Critique of Arab Reason argued that from Arabic grammar to Islamic law, foundational Islamic texts contained the nucleus of irrationalist and magical thinking. Mohamed Abed Al-Jabiri’s Critique of Arab Reason argued that from Arabic grammar to Islamic law, foundational Islamic texts contained the nucleus of irrationalist and magical thinking. |

The most important work of the genre, and by far the most influential Arab intellectual work of the 20th century, was the four-volume Critique of Arab Reason, an obvious play on Kant, by Moroccan thinker Mohamed Abed Al-Jabiri. In his work, Jabiri provided a systematic analysis of foundational Islamic texts showing that everything from Arabic grammar to Islamic law contained the nucleus of irrationalist and magical thinking. His work was a triumph for the calls for more Enlightenment-style rationalism, generally understood as a refined Marxism with clearer atheistic presuppositions. The second most prominent intellectual of the genre was Algerian French Sorbonne professor Mohamed Arkoun. If Jabiri wanted to follow the Frankfurt School’s lead and push revolutionary thought toward Marxism’s roots in Enlightenment rationalism, Arkoun wanted to go the other way, following the lead of postmodernism, in rediscovering Marxism’s other roots in Romanticism. Arkoun brought Derrida and Foucault, without ever saying so explicitly, to bear in excavating Islamic Arab epistemology to uncover its deep layers of power relations obscured by myth and Quranic semiotics. Jabiri and Arkoun still occupy the center of Arab high culture intellectual life.

Below the high culture and sophisticated analysis of the new left, a populist new left emerged, primarily centered in Lebanon, fueled by the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish and Ali Ahmed Esber, known by his pagan pen name Adonis, and by the writings of Ghassan Kanfani. The rising Palestinian guerrilla groups, Fatah and the PFLP, a splinter Marxist group from the quasi-fascist Arab Nationalists’ Movement, managed to overthrow the old left from the leadership of the PLO and took its place—a development which was seen as an inspiration to all the Arab new left forces dreaming of overthrowing and replacing the Arab old left. The Palestinian guerrilla groups, inspired by Régis Debray, were making a “revolution inside the revolution,” a natural outcome of the urge to invert devastating defeat into a decisive victory.

This revolutionary subversion inside the Arab revolutionary movement managed to invert the conception of the Palestinian cause. Pre-1967, Arab nationalism held that Arab unity was the road to Palestine. Post-1967, the Palestinians inverted this Hegelian motto by turning the salvific dream of a destroyed Israel and a liberated Palestine into the essence of the revolutionary mission itself. “Palestine is a revolution,” became the new self-conception of the rising Palestinian factions, adding it to the ranks of a transnational anti-capitalist revolutionary movement that included Vietnam, Cuba, Black Power in the U.S., German Marxist terrorism, and others. After their expulsion from Jordan, Palestinian groups declared their plan was to turn Lebanon into an “Arab Hanoi” from which a popular liberation war and a total revolution would revolutionize the entire Middle East. This was the decade in which Palestinian groups laid the grounds for international terrorism of plane hijacking, assassinations, and bombings.

It is important to mention here that in all the ideological tracts and literature of the Palestinian groups, the works of French and communist intellectuals were continually quoted. The first Fatah newsletter after the Munich Olympic Village terrorist attack featured quotes from Fanon on its cover.

To the right of the new Arab left was the Islamic left, a group of committed Marxist intellectuals who decided to apply Maoist principles of popular mobilization and saw Islam as the most suitable vehicle to do so. It was not uncommon for Arab Marxist Christian intellectuals, such as Munir Shafiq, to convert to Islam and become Islamic Marxists. In Egypt, the strongest base of the Islamic left, this milieu of intellectuals was led by Abdul Wahab Al-Missiri, Hassan Hanafi, Mohamed Imara, Adel Hussein, and Nasr Abu Zayd. Missiri, a student of Nazi sympathizer Abdulrahman Badawi, focused entirely on synthesizing a Marxist-Islamic critical theory of Zionism and Judaism, depending on Lukacs, Marcuse, but above all Mannheim’s sociology of knowledge in producing a seven-volume critical deconstruction of all of Jewish history and culture, revealing its inherently colonialist, imperialist, and dehumanizing nature. When Missiri was once asked about what remained from the Marxism of his youth, he answered, “Nothing and everything … my Marxism dissolved into Islamic humanism.” Others, such as the Islamic thinker Hassan Hanafi, who is the teacher of the current generation of Egyptian intellectuals, maintained that Marxism is identical to Islam.

By the time of the Iranian Islamic Revolution, in which Khomeini demanded “dissolving all ideologies in Islam,” there was enough public interest in a potent mixture of Islamic fundamentalism, existentialism, and Marxist revolutionary thought embodied in intellectuals like Ali Shariati for a wave of conversion to political Islam to overtake the ranks of Maoist and Marxist Lebanese and Palestinian militants and intellectuals, for whom Islam would become the gateway back into the embrace of the masses.

In Egypt, Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, had the ambitious plan of ending Egypt’s leftist and pro-Soviet orientation and transforming Egyptian politics and culture to fit inside the Western camp. This ambition was centered around the achievement of recognition and peace with Israel, to which the population and the intellectuals were opposed. The fierce resistance Sadat met from the hegemonic establishment of Nasserist and leftist intellectuals led him to resort to two strategies: political repression of intellectual life, and a restoration of Islamic conservatism, and even fundamentalism, in order to maintain popular support for the state.

Unbeknownst to Sadat, by that point, religious thought had completely dissolved into revolutionary thought to an extent that made it impossible to provide a nonrevolutionary reading of Islam. In turn, the definition of intellectual life itself had been profoundly altered to exclusively mean “leftism.” Egyptian intellectuals, poets, and journalists filled Egyptian culture with anti-Sadat, anti-American, and antisemitic works. Folk poets wrote songs mocking Coca-Cola and the American lifestyle. Young novelists such as Sonallah Ibrahim wrote novels about a protagonist eating himself into annihilation because of the invasion of Coca-Cola capitalism. Amal Donqol, a talented poet, wrote his infamous poem “No reconciliation,” exalting the eternal worship of vengeance upon Israel.

Shortly before his assassination by Islamic revolutionaries, Sadat signed an order to arrest over a thousand Egyptian intellectuals. After his successor, Mubarak, came to power, and with the dangers of an Iranian-styled Islamo-Marxist revolution ever closer, he released the imprisoned intellectuals, made peace, and restored them to their various chairs heading the universities and media agencies. A division of labor was established where the state would deal with Israel and the U.S., while intellectuals were responsible for maintaining an anti-American and anti-Israel national culture, a situation recognized today in Egypt as the “cold peace.” Hamas, Hezbollah, 9/11, Baathist Iraq, the Arab Spring, and the Islamic State are all downstream from this intellectual story.

Leftist intellectuals such as Judith Butler and Noam Chomsky are therefore not wrong when they declare that Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iran are part of the international left. A journey of philosophical inversions started from a Hegelian inversion of Christian theology, then a Marxist inversion of Hegelianism, a fascist-Nazi inversion of Leninism, the globalization of European thought, the conversion into Arab nationalism, its fragmentation into Arab Marxism and Palestinian radicalism, and their inversion back into theology, creating an ideological tornado with antisemitism as its vortex. The aggregate result was the gradual decivilization, and moral and social erosion, of entire Muslim and Arab societies, many of which collapsed unto themselves in spirals of self-destruction.

The dissolution of religious thought of otherworldly transcendence into a political transcendence inside history fundamentally transformed and restructured the identity of Islamic religious piety into the piety of struggle. Muslim identity was remolded into an eternal struggle that in its origin is not the jihad of classical texts, but the German dialectic world made by Marx. A religious doctrine of martyrdom and eternal life in the hereafter merged into a cult of the eternal revolutionary glory and hero worship of the Che Guevara type. This is the best explanation one could offer for the peculiar phenomenon of Muslim societies becoming more religious since the late 1970s in a way that only translated into more rage, more rebellion, less moral restraints on violence and sexuality, and conspicuous pagan worship of pain, blood, and misery. This is also the best explanation for why the societies of the Arab Gulf, which did not modernize during the 20th century, seem to have a much smoother transition away from antisemitism into social liberalization and peaceful worldviews.

Let’s assume I’m correct, and Islamists got this idea by way of a global revolutionary culture that got it from Lenin who got it from Marx who got it, not by way Plato as Popper assumed, but by way of rediscovery through inverting Hegel’s inversion of Christian theology. Doesn’t this theory naturally fall right back into the religious dogmatism that is associated with Marxist intellectuals? Raymond Aron rightfully thought so in his Opium of the Intellectuals. Theory then reverts into a theology that becomes a political religion waging religious wars, schisms, ancestral worship, and textual fanaticism. Theology made philosophy by Hegel, philosophy made politics by Marx, and then politics was made into a religion. So naturally, Qutb’s and Khomeini’s conversion of the Marxist inversion reverted back into theology. But what does theology lose by this double inversion and what does it gain? Much. It becomes a religion of atheistic politics. It loses all its basis of religious justification and with it its entire moral structure and becomes an immanentist atheistic theology that leads to no redemption, no transcendence, and nowhere.

I want to emphasize what this article is not saying. I’m not saying that any form of Islamic fundamentalism could be attributed to modern revolutionary thought. Indeed, all religions have their own forms of modern fundamentalism as a response to modern liberal social organization. But Islamic fundamentalism proper means a rigid and ultra-conservative social ethos that is resistant to social change, as best exemplified in the Salafism that until recently dominated the Arab Gulf.

What the union of imported European ideologies like Marxism, Nazism, and existentialism with Islam accomplished was to profoundly alter the entire conceptual scheme and epistemological foundations of Arab societies so that even Islamic fundamentalism, unbeknownst to itself, could no longer provide a pre-revolutionary reading of Islam. European moral philosophical traditions and their language managed to make a tectonic shift that resulted in the development of a modern Islamic political theology that is totalitarian, dystopian, and revolutionary. The Islam of Iran, ISIS, the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, Hezbollah, and al-Qaida is simply a regional variant of progressive Western revolutionary thought.

Yet I am not saying that the West is to blame for this development. For if this article seeks to affirm anything it is that the West-Islam dichotomy is not only meaningless but delusional. Cultural and moral relativism are meaningless when the foundation of all our modern moral and political thinking comes from the same place. Europe has managed to create a truly global human culture that no longer has ideational barriers and in which fashion, style, fads, and ideas form global mimetic contagions.

This is a story of a global nightmare constructed by intellectuals from all religious and national backgrounds. The Enlightenment and its aftermath are now just as solidly a part of Islamic intellectual makeup as they are in Western cultures, and if the Muslim world is to move forward it would be through the recognition and not the denial of this fact. If the moral and social destruction of the region resulted from incompetent Arab intellectuals sleepwalking in the orbit of a global culture, the solution is competence. The exploitation of the intellectual, social, and political energies of impoverished and pre-modern societies for use as cannon fodder in the great ideological battles of the Western left has had disastrous effects on the social, economic, and political development and progress of many Arab and Muslim societies. In this regard, the Western left’s theology of how the West destroyed other societies has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, from which it is now our duty and obligation to liberate ourselves.

Hussein Aboubakr Mansour is the Director of EMET’s Program for Emerging Democratic Voices from the Middle East and a writing fellow at the Middle East Forum.