The country is too big to fail, but no one is rushing to its aid.

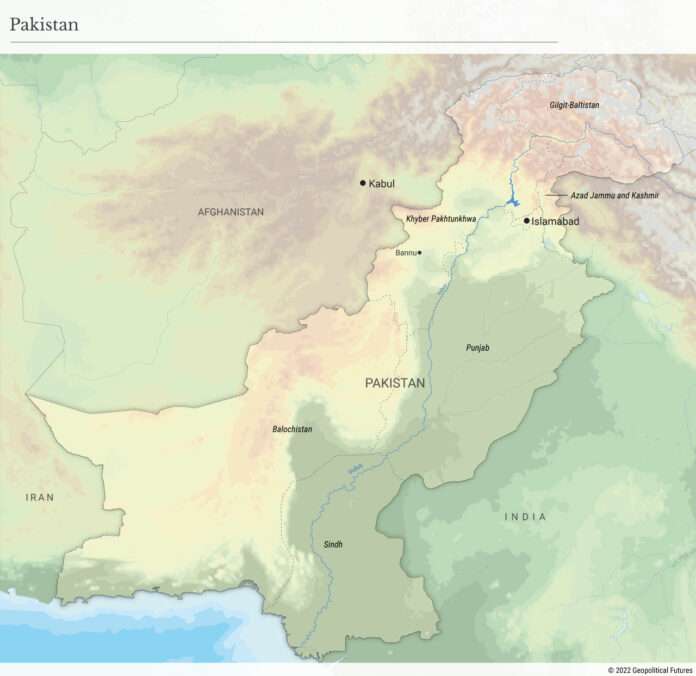

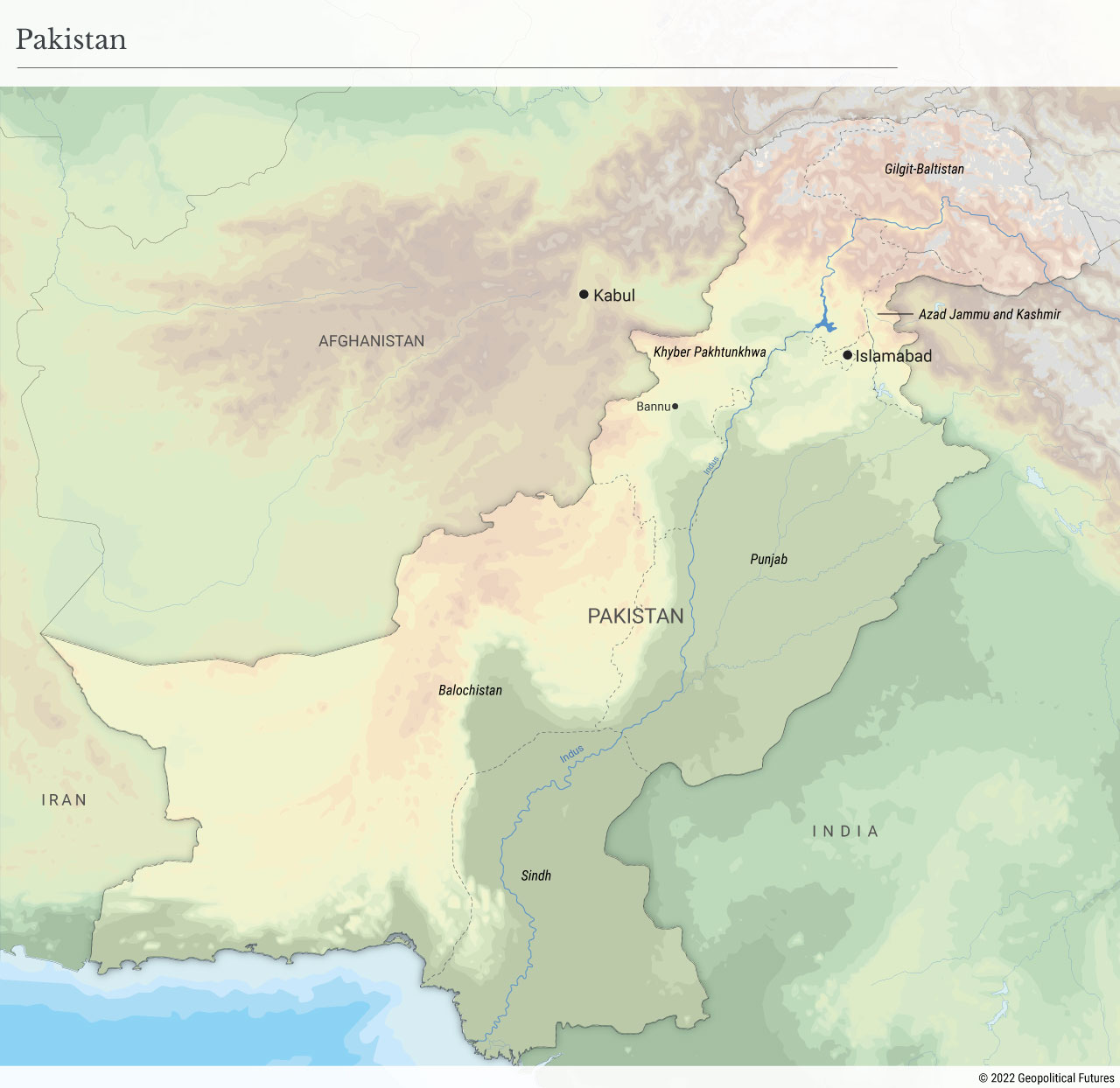

Decades-old political economic problems in Pakistan are coming to a head. The South Asian nation needs billions of dollars in financial assistance to avoid a default at a time when its usual patrons are disinclined to bail it out. The International Monetary Fund is insisting on tough reforms that the fragile coalition government cannot institute without taking a major political hit in an election year. Even if Islamabad dodges this particular bullet, it will have to massively overhaul the way it has managed the world’s fifth-most populous country. If it cannot, then it will further push Pakistan toward a systemic breakdown, which has major consequences for security in the world’s most densely populated region.

Out of Options

An IMF team is visiting Pakistan from Jan. 31 to Feb. 9 to continue discussions on the release of $1.18 billion in assistance, part of a $6 billion aid program that was agreed on in 2019 (and increased to $7 billion in 2022) but that has since stalled. Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves have slumped to about $3.68 billion, barely enough to cover three weeks of imports. Inflation was already at 25 percent when the government announced on Jan. 29 a 16 percent hike in gasoline and diesel prices that will likely rise much further. Three days earlier, the Pakistani rupee fell 9.6 percent against the dollar, the biggest one-day drop in over two decades, after the government removed unofficial caps and allowed the currency to move toward a market-based exchange rate.

Earlier in the month, the country’s civil and military leadership traveled to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to secure the funds needed to avert a financial meltdown. Reports surfaced that Riyadh and Abu Dhabi would provide several billion dollars. In sharp contrast with their past behavior, they aren’t willing to write a blank check; the Saudi finance minister said Jan. 18 that the kingdom was no longer providing “direct grants and deposits” to debtor nations without seeing reforms. The Saudis, the Emiratis and others who could provide the cash want to first see the Pakistanis accept an IMF program. Besides, the beleaguered South Asian nation’s financial needs far outstrip the global appetite to assist.

Islamabad, however, has been struggling to finalize what would be the country’s 23rd IMF arrangement since it first knocked on the lender’s doors in 1958. The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party, which heads the fragile and increasingly unpopular coalition government, has a lot to lose by agreeing to IMF terms that are bound to exacerbate harsh economic conditions. As it is, the PML-N and its allies are facing an uphill electoral battle against the populist opposition Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) party of former Prime Minister Imran Khan.

Still, Pakistan’s political instability is the result of a much deeper malaise. Since the end of Pakistan’s fourth military dictatorship in 2008, the country nominally has experienced its longest stretch of civilian governance. 2013 marked the first time one democratically elected government transferred power to another. But the army continued to encumber both governments, and in 2018 it engineered the rise to power of Khan’s PTI in hopes that it would finally have a pliant civilian actor. That experiment was a colossal failure. It has weakened the military politically and has thus plunged the country into uncharted territory.

A similar situation has emerged on the economic front. Pakistan has always had financial problems, which over the decades continued to worsen. The country got by only because of a periodic influx of U.S. assistance, made possible by the broader global geopolitics of the time. There have been three such long periods – 1958-69, 1977-88 and 1999-2008 – each under a different military regime and coming at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, and the post-9/11 war on terror, respectively. In today’s changed circumstances, Pakistan is facing an unprecedented financial crisis because it never developed a viable economy and is without external bailout options.

The Nightmare Scenario

Without a major reform process – which is unlikely given the acute state of social and political divisions – Pakistan’s situation is likely to worsen. Its annual population growth rate is 1.9 percent, which is 237 times that of the global rate, and its fertility rate exceeds the global rate by 157 percent. At this pace, in another 10 years the country will have added 50 million people, increasing its population to 275 million. There is already a massive youth population. Sixty percent of Pakistanis are under the age of 23. As many as 44 percent of all Pakistani children between the ages of 5 and 16 do not attend school. Females make up almost half the population, and literacy among them is at 48 percent.

Dealing with the multiplicity of crises plaguing the country requires a political consensus. This is extremely difficult in the current highly polarized political climate, which is unlikely to abate anytime soon. Pakistan’s powerful military establishment, which has intervened in politics for much of the country’s history, is in an unprecedented dilemma. After the failure of its latest attempt to shape the country’s political economy, which ended with the April 2022 ouster of Khan, the top brass publicly committed to keeping the army out of politics. Rationalizing the economy, however, will take a long time – assuming the country’s tumultuous politics can be brought under control (a big if).

In moments like these, when normal politics produces only more chaos, the pressure (or temptation) for the army to hit pause or reset on the constitutional process is high. However, the general staff has been down that road many times, only to end up exacerbating the problems it aimed to solve. When problems are such that degradation is happening much more quickly than is the realistic efforts to fix them, stalling the political process could be akin to an out of the frying pan and into the fire type situation.

The only other option is to continue the slow path toward recovery, which is fraught with perils. As large swathes of the population suffer under the weight of debilitating economic conditions, intra-elite political struggles intensify. These are precisely the conditions that Islamist militants – both Taliban rebels and Islamic State militants ensconced in the neighboring emirate in Afghanistan – hope to exploit. A resurgent jihadist insurgency will likely force an already weakened Pakistani state into a new major military campaign – one that has serious potential to spill over across the border.

It is this nightmare scenario – a cash-strapped Pakistani state whose security is compromised on its western flank – that will eventually result in Arab Gulf states, China and the United States gaining greater influence in the country. Washington cannot allow Pakistan to descend into chaos, especially with Afghanistan under a Taliban regime. Likewise, China, which has pumped tens of billions of dollars’ worth of Belt and Road funds into the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, is not going to sit by and watch its investment sink. Pakistan is thus going to become an even bigger arena for the U.S.-Chinese competition. Meanwhile, the Saudis and the Emiratis, who have long played a major role in periodically mediating intra-elite power struggles in Pakistan, will likely have greater influence over Pakistan’s internal workings. In India, which only months ago surpassed the U.K. to become the world’s fifth largest economy, there is immense concern over how a financially collapsing Pakistan could affect New Delhi’s upward trajectory.

While it is too early to speak with any specificity on how external powers will behave, Pakistan can’t continue to chug along as it has. It may not always appear this way, especially in chronically fragile states, but long-term dysfunction adds up. Major fissures have emerged that outstrip Pakistan’s available resources, disrupting the status quo in which it was able to get by for so long.