By Agha Hussain

November 03 2021

Iran’s recent reactions to events in Afghanistan’s northern reaches and the Iran-Armenia-Azerbaijan border area were sudden and dramatic. Viewed in the context of certain overarching regional trends, they appear to be part of the rapid development by Tehran of a new hard-power oriented strategic posture toward its Eurasian neighbourhood.

The Panjshir false alarm

In mid-August, an alliance vowing to defy the new Taliban regime coalesced in northeastern Afghanistan’s Panjshir province. The inevitable clash between the two sides was closely covered by Indian media, which broadcast clips from combat videogames under the headlines of Pakistani military involvement on the Taliban’s behalf.

The disinformation campaign was not surprising, but wholly consistent with New Delhi’s continued view of the Taliban as outright proxies of, or very close allies, to Pakistan. What was surprising, however, was the apparent buy-in for the disinformation in Iran.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry condemned the Taliban’s advance on Panjshir and stated that Iran should ‘review’ the reports of Pakistani involvement.

Iran’s strong criticism of the Taliban over the matter of a few heavily outmatched enclaves of resistance in Panjshir and association of their actions with Pakistani meddling was unlikely to be driven by genuine belief in the Indian media reports. The reports merely served as Tehran’s pretext to establish its willingness to exert pressure on the Taliban and its firm expectation that their domestic policies account for Iranian political preferences.

This stance is tailored to Iran’s desired integration of post-US withdrawal Afghanistan into its geopolitical network of allies. Indeed, the Taliban’s ascent as an Islamist non-state actor with its political power stemming from its military prowess interests Iran greatly since most of its own allies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Yemen closely match this description.

However, the Taliban also need to be reminded that a resurgence of anti-Shia practices, which would forestall any alliance with Iran’s regional axis from their previous period in power (1996-2001), will lead to problems with Tehran.

Iran has already been preparing itself for this leadership role in Afghanistan by building space and scope for itself to conduct its Afghan policy unilaterally. An example of this was its rejection of Moscow’s invitation to join the Russia-US-China-Pakistan ‘Extended Troika’ platform for multilateral diplomacy and coordination over Afghanistan.

Russia’s special envoy for Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov described Iran as one of the most important players in Afghanistan and lamented its absence, which stood out starkly as Iran shares several fairly urgent concerns with the Extended Troika, such as coordinating to prevent an Afghan refugee exodus and ensuring the Taliban stamp out the presence of ISIS-K (Khorasan).

Iran made no official statement on its decision to not join the Extended Troika, but Kabulov publicly stated that this was due to its tensions with the US. Ultimately, abstention from the platform showed that Iran has concerns which warrant participation in multilateralism a lesser priority than the geopolitical objectives which Tehran intends on pursuing unilaterally.

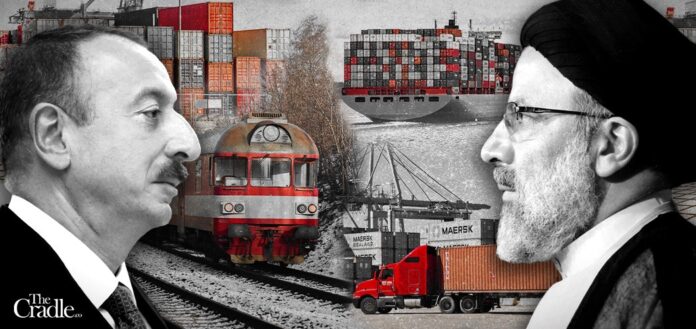

Azerbaijan amidst the Iran-Israel conflict

On 30 September, Iran announced large military drills on its border with Azerbaijan. The drills, tasked with demonstrating Iran’s combat-readiness, were named the ‘Conquerors of Khayber’ in reference to the Battle of Khayber in 628 CE fought between the early Muslims and a Jewish army.

Both the name and the timing of the drills were carefully selected; Iran sought to assail Azerbaijan’s relations with archenemy Israel and to show that the earlier Azerbaijan-Turkey-Pakistan military drills would not deter it from confronting Baku on this issue.

The drills also followed the detention of Iranian trucks crossing through Azerbaijani territory en route to parts of the contested Nagorno-Karabakh enclave still held by Armenia. This provided Iran the pretext it needed for a military build-up at the border with Azerbaijan.

The editor of Eurasianet for Turkey and the Caucasus, Joshua Kucera, described Iran’s military posturing as unprecedented and the reinvigoration of its focus on Azerbaijan-Israel ties as conspicuous, stating that the issue of the trucks alone could not have caused it.

Instead, the Conquerors of Khayber was Iran’s way of emphatically staking out its position against regional trends in the balance of power and military dynamics in the Caucasus driven by Azerbaijan’s victory against Armenia in the war over Nagorno-Karabakh last year.

Pushing the envelope

Iran views the major role Israeli armaments played alongside Turkish ones in the Azerbaijani victory as having boosted Israel’s status in Baku’s strategic calculus as a reliable extra-regional backer for the latter’s more assertive posture in the Caucasus.

Tehran wishes to forestall nearby states from so perceiving cooperation with Israel as a vector for power in the Caucasus, especially considering its own notable lack of impact on the Nagorno-Karabakh war. In this endeavour, Azerbaijan is at present both an ideal and urgent target.

Iran interprets various Azerbaijani regional goals as serving Israeli interests and now opts to use the threat of escalation and region-wide rivalry with Azerbaijan to make it take this interpretation seriously. Doing so will allow Iran to directly obstruct or challenge these goals with the result that Baku agrees to cut back its dealings with Tel Aviv.

This approach is presently being applied to the planned ‘Zangezur Corridor’ between Azerbaijan and its autonomous Nakhchivan exclave via Syunik province in south Armenia.

Mandated by the November 2020 Russian-brokered Azerbaijan-Armenian ceasefire treaty, the corridor is one of Baku’s most prized war spoils as it would link Azerbaijan and Turkey directly by land for the first time.

As noted in an Atlantic Council article by Iranian analyst Abbas Qaidari, the view of the Zangezur Corridor as a gateway for Israel to the Caucasus has gained tract in Iran.

In his 6 October visit to Moscow, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian followed his proclamations of an Israeli threat to regional stability with warnings against ‘map change’ and ‘geopolitical change’ in the Caucasus. This was a not quite veiled reference to the Zangezur Corridor, which on account of running parallel to Iran’s border with south Armenia is being dubbed by Iranian military-run media outlets as an Azerbaijani-Turkish-Israeli ploy to block the Iran-Armenia border from above and to bring Israel to Iran’s doorstep in retribution for Tehran’s strategic depth in Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria.

The Conquerors of Khayber drills and Abdollahian’s remarks burden Azerbaijani initiatives in the Iran-Armenia border region such as the Zangezur Corridor with considerable strategic risk. Armenia will be emboldened by Iran’s newfound hostility to the corridor into non-compliance with the corridor’s transit through Syunik, placing pressure on Baku to live up to its pledge to forcibly implement the corridor if need be; and the resultant Azerbaijani military posturing at the Armenian border can then be used by Tehran as an excuse to climb further up the escalation ladder, possibly by militarily allying with Yerevan.

Azerbaijan can avert such a situation if it accommodates Iran’s Israel-related concerns via tangible steps, such as instituting intelligence sharing with Iran over the areas where the Zangezur Corridor is to pass. Not doing so will allow Iran to cement the idea of Azerbaijan as an Israeli beachhead into its Caucasus policy and accordingly extend the zero-sum stance it has adopted toward the Zangezur Corridor to other Azerbaijani interests.

Shaking up Caucasus connectivity

Iran has already signalled its willingness to do this, expanding its focus to Azerbaijan’s East-West connectivity interests. To this end, Iran’s deputy transportation minister Kheirollah Khademi visited Yerevan on 4 October to affirm support for increased road linkages with Armenia.

Iranian state media highlighted the visit’s broader purpose to bypass Azerbaijan in Iranian-Armenian trade and to build a trade and transport corridor to Europe via the Iran-Armenia-Georgia-Black Sea-Bulgaria-Greece route.

What makes this notable is the fact that Iran is already part of a shorter, quicker and prior-tested route to Europe: the North South Transport Corridor (NSTC) connecting India to Europe via the Indian Ocean-Iran-Azerbaijan-Russia-Finland route.

By promoting the otherwise redundant route via Armenia, Iran demonstrates that its aggravated tension with Azerbaijan – caused by its ties with Israel, in Tehran’s view – is steadily spilling over into the connectivity realm and creating a new challenge to Baku’s connectivity windfall.

Moreover, Azerbaijan cannot write off this particular pressure tactic as empty posturing because of US sanctions inhibiting Iran from such expansive economic plans.

In July, the European Union (EU) announced an aid package for Armenia worth over $3 billion including 600 million euros to expedite progress on the North South Road Corridor. This road will extend from the Iran-Armenia border to the Armenia-Georgia one to join with further transport links to Europe via the Black Sea-Bulgaria-Greece route.

The unprecedented aid represents renewed European efforts to prevent over-reliance on Caucasus-Europe trade routes and links terminating in Turkey, where essentially all of Azerbaijan’s vital East-West connectivity links terminate. This particular consideration previously led the EU and the US to decline funding for the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway project which Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey then completed with their own funds in 2017.

Importantly, India itself has signalled intent to replace Azerbaijan with the Armenia-Georgia-Black Sea route as the NSTC’s Caucasus leg, as a riposte to the Azerbaijani-Turkish embrace of Pakistan.

India’s Ambassador to Iran, Gaddam Dharmendra, alluded to this in early March while India notably left Azerbaijan out of the international ‘Maritime India’ virtual NSTC summit it hosted days later. Indian Foreign Minister Subramaniam Jaishankar similarly omitted Azerbaijan during a joint press conference with his Armenian counterpart Ararat Mirzoyan in Yerevan on 13 October, addressing Armenia instead as an NSTC stakeholder.

Hence, challenging Azerbaijan’s connectivity interests can be a cogent, durable policy option for Iran. The critical mass of international cover lent to its aggressive Caucasus posture by a convergence of European and Indian interests upon the Iran-Armenia-Georgia-onward corridor will trouble Azerbaijan.

Iran has a generally high threshold for enforced isolation as a cost for hard-power projection; with such influential capitals as Brussels and New Delhi logically interested in separating its Caucasus policy from the contexts that typically surround US anti-Iran sanctions, Tehran will be greatly reassured about the sustainability of its tough stance against Baku.

The Russian factor

The overall plausibility of Iran’s counter-Azerbaijan corridor plan is also boosted by its equilibrium with Russia’s present geopolitical preferences in the South Caucasus.

The Azerbaijan-Armenia ceasefire treaty that Russia brokered obligated Yerevan to allow the Zangezur Corridor, but also allotted Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) the role of overseeing the corridor and other Azerbaijan-Armenia transport routes. This showed that while Russia accepts that Turkey’s decisive military support to Azerbaijan earned it the status of a power-broker in the South Caucasus, Ankara’s inroads in this former-Soviet space are under close watch by Moscow who in turn has ramped up its own regional presence.

Russia will find the Iran-Armenia-Georgia-onward corridor project useful to this strategy of containing and modulating Turkey’s advance in the South Caucasus. The corridor bypasses Turkey and thus, if developed, will offset Turkish dominance as the South Caucasus and especially Azerbaijan’s gateway to Europe.

The leverage this gateway role gives Turkey over Azerbaijan is its best chance at coaxing Baku to – as Azerbaijani analyst at the Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor Rahim Rahimov puts it – “become more involved in Turkish geopolitical plays” far outside the Azerbaijan-Armenia context.

In lieu of this, Russia’s unique ability to either greatly improve or hinder the corridor’s development warrants Ankara’s respect for Moscow’s regional preferences and red-lines.

For example, Russian Railways has owned and operated the entirety of Armenia’s railway industry since 2008, making Russian approval necessary for the construction of new and bigger Iran-Armenia-Georgia rail links, which allow faster and cheaper international freight transport than roads do.

Conversely, Russia’s support would free the corridor project of major obstacles, such as European hesitancy to tread upon the Russian monopoly in Armenia’s transport sector, or potential concern in New Delhi that redirecting Indian trade with Europe from the NSTC via Russia to the Iran-Armenia-Georgia-onward corridor will offend its strategic partner by depriving it of transit earnings.

Thus, Russia can derive an effective bargaining chip with Turkey and Azerbaijan from its position on Iran’s corridor project. This will prove especially useful in the context of growing Turkish involvement near Russia’s vast Eurasian borders, from Ukraine to the Caucasus and the Central Asian Republics, in the military and connectivity spheres traditionally dominated by Moscow.

Such a scenario will be a more than satisfactory outcome for Iran, building upon growing European and Indian interest in actualizing the corridor.

High stakes in Eurasia

Deadly successive terror attacks upon Afghan Shias by ISIS-K and heated rhetoric from Azerbaijan will register in Iran as further evidence of the need for a hard-power oriented approach to securing its interests in Eurasia.

Tehran has not positioned itself as prominently in the Caucasus or Afghanistan as it has in the Middle East since it underwent its Islamic Revolution in 1979. Watershed events such as the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh have helped remind it of the urgent need to do so. The balance of power and geopolitical status quo in these crucial Eurasian sub-regions are in flux and a forceful, assertive posture may be Iran’s best bet at influencing them to its advantage.

Each of the numerous hard-power strategies Iran has available at its disposal comes with its own set of issues and challenges, but altogether, these offer considerably more impact to Tehran than a passive, diplomacy-oriented Eurasian posture.