In early April, President Trump stood in the Rose Garden with King Abdullah II of Jordan, a strong ally of the United States, and someone who had been dismayed by America’s Middle East policy under Barack Obama. By then, Trump had been briefed twice on the chemical weapons attack in Syria. He had been “absolutely sickened,” an aide put it, by the images of “babies, little babies,” as the enraged president put it, dying slow, torturous deaths. No one needed to mention that Trump’s eighth grandchild, Theodore, the son of his daughter Ivanka Trump and her husband Jared Kushner, is just one year old, and had first begun to crawl in the White House earlier this year. Trump’s emotion was real—and raw.

Related: The Risks of Trump’s Strike on Assad in Syria

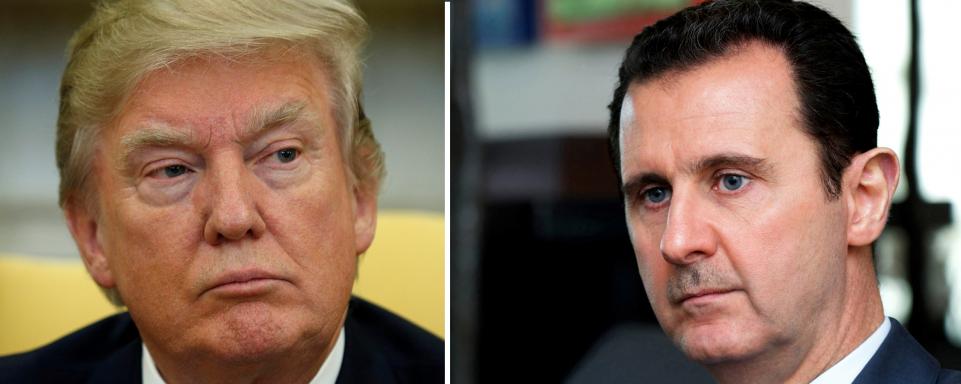

In 2013, Trump had taken to Twitter, saying it was foolish for the U.S. to get involved after Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s forces had used chemical weapons against civilians—a judgement Obama ultimately shared. That was then. In early April, however, Trump’s national security adviser, H.R. McMaster, and Defense Secretary James Mattis, had laid out the evidence. U.S. intelligence was “highly confident” that the Syrian air force under the command of Assad had carried out the heinous attack. Trump had to make a choice. To not respond, a la Obama, was a message to the world: the United States will not punish you for using sarin gas to murder your own people.

Trump asked the Pentagon to give him options—and it had plenty, since the Syrian civil war has been going on for six years. By late afternoon on April 6, just before the president was to meet China’s President Xi Jinping, the Trump team had settled on a preferred option: the U.S. would quickly strike the air base from which the Syrians had launched their chemical attack. An hour in advance, the U.S. military used the “deconfliction line” set up with Moscow to prevent military mishaps in Syria. The message: Get your folks off the Shayrat air base, near the city of Homs, right away. At 7:40 p.m., as Trump was having dinner with Xi, two U.S. Navy destroyers in the eastern Mediterranean launched more than 50 Tomahawk missiles, demolishing much of the base and the aircraft on it.

It was a symbolic strike, one designed to send a message. But the impact was still stunning. “Rarely in the history of military affairs has such an insignificant military strike been so significant,” says Michael Doran, a former National Security Council staffer during the George W. Bush administration. Consider the context. Over the past month,Trump had met the U.S.’s traditional Sunni Arab allies in the Middle East: Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al Sissi and finally Crown Prince Abdullah. All had been angered by what they saw as the Obama administration’s deliberate tilt toward the Shiite government in Tehran, a position borne of the desire to obtain a nuclear deal with Iran (which it achieved) as well as a belief that the two warring sides of Islam are best left to sort things out themselves. So the Syria strike came as Washington was working to re-energize its traditional Middle East alliances and to signal that the new administration still views Iran as a malignant force in the region.

This shift has potentially major implications. We may be seeing the first glimmerings of a Trump foreign policy doctrine. Critics of Obama’s policy say the tilt toward Tehran hindered the fight against the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) group— Trump’s first priority upon assuming office. The fact that Iran-backed Shiite militias have been fighting in Iraq has kept many Sunnis on the sidelines or openly siding with ISIS. This is part of the reason why the fight to regain Mosul in Iraq, or to finally reclaim Raqqa, the de facto capital of ISIS in Syria, has been so halting. As the mideast analyst Lee Smith has written, the Obama administration seemed blithely indifferent to that reality.

The Trump administration is not so indifferent. Both Mattis and McMaster, former generals with long experience in Iraq, have a more hard-headed view of Tehran, and have encouraged the president in his outreach to Arab allies. How far Trump is willing to go in creating his new doctrine, however, is still far from clear. The president is still said to be considering further measures in response to the sarin attack, but there is no indication yet what those are. Meanwhile Moscow, whose forces are integrated with Syria’s (as are Iran’s), remains a huge obstacle. In response to the Tomahawk strike, Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to shut down the deconfliction line in Syria—a stupid, but not unthinkable move.

On April 12, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson heads to Moscow with an important message for Putin: the U.S. now has a president who doesn’t erase red lines, and you and your stooge in Damascus should understand that. The negotiations for a Syrian settlement have never gone anywhere; there are many reasons for that, but one of them, arguably, is that Washington has applied too little pressure on Tehran and Putin to rein in Assad.

Moscow has already said its support for the Syrian strongman is not “unconditional.” Tillerson will certainly test that, backed by the knowledge that less than 100 days into his presidency, the “America First” candidate has emphatically shifted the U.S.’s focus away from home.

http://www.newsweek.com/trump-syria-airstrike-assad-putin-russia-syria-america-first-bannon-kushner-580899

Newsweek

Newsweek