BY ISHAAN THAROOR The Washington Post

BY ISHAAN THAROOR The Washington Post

Edited by Max J. Rosenthal and Kazi Awal

After a hideous terrorist attack on a mosque in north Sinai, which killed at least 305 people on Friday, Egypt’s strongman president, Abdel Fattah el-Sissi, issued a characteristically tough warning. He promised “brute force” and an “iron fist” in response to the shocking attack, which was linked to an Islamic State affiliate that has gained a foothold on the Sinai Peninsula.

Though Egypt is no stranger to extremist violence, the scale and brazenness of the assault stunned the nation.

“Survivors and officials described five pickup trucks carrying up to 30 gunmen — some of them masked — converging on al-Rawda mosque as the imam began his sermon,” my colleagues reported. The gunmen reportedly bore Islamic State flags. “Some worshipers died in a suicide blast; others were gunned down as they ran. The attackers would later walk among the fallen, 27 of them children, shooting those who appeared to be breathing.”

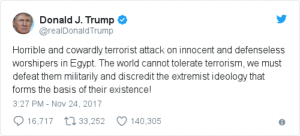

President Trump decried the attack on “innocent and defenseless worshipers” and used the occasion to again denounce extremist Islamist ideology. He also renewed calls for a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border, though analysts largely reject the notion of any vast jihadist infiltration into the United States from the south.

Despite Sissi’s repressive rule, under which thousands of suspected Islamists and dissidents have been detained and the space for civil society has been squeezed, Trump remains the Egyptian president’s loudest cheerleader in the West. He has hailed Sissi’s no-nonsense attitude and his recognition that “this ideology of death” — a reference to Islamist extremism — “must be extinguished.”

But it doesn’t seem that Sissi is doing a particularly effective job. His government attempted to cast the Friday attack on the al-Rawda mosque as a sign of the “weakness, despair and collapse” of jihadist forces, who resorted to hit a soft target rather than Egyptian security forces. But the Egyptian military has been engaged in a grueling and bloody counterinsurgency in northern Sinai for years — particularly since Sissi came to power in a 2013 coup — and both their campaign and the terrorist attacks show no signs of winding down.

Sinai, a vast region that straddles the arid borderlands between Israel and Egypt’s Nile Valley, has endured an alarming degree of violence. As my colleague Adam Taylor noted, “there have been more deaths from large-scale terrorist attacks in Sinai this year than there had been in any other country except for Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia — all of which have populations at least 10 times larger than Sinai.” Nearly 1,000 Egyptian security personnel have died there since 2013.

Sissi’s approach, analysts say, has not helped the situation. Heavy-handed tactics have alienated an already embittered civilian population. Rights groups reported earlier this year that Egyptian troops carried out the extrajudicial executions of unarmed detainees. Amnesty International detailed a campaign of torture, disappearances and assassinations conducted by Egyptian authorities.

“The military has never cared for civilian losses,” said Mohannad Sabry, the author of a book on Sinai, to the New York Times. “The excessive and reckless use of force has killed entire families. We’ve seen airstrikes blow people up in their homes. We’ve seen villages razed off the face of the earth. That tells you something about how they see Sinai society.”

The same article quotes a local woman speaking to reporters outside a hospital that was tending to victims of the attack. “The military will keep jailing and killing local young people. The terrorists who hate us and the Christians will keep using it as an excuse to kill us,” she said, while refusing to give her name or continue the conversation. “There is no point in talking about anything.”

For analysts and policymakers, however, Sinai is a critical place to watch. As the Islamic State’s supposed “caliphate” crumbles in Iraq and Syria, attention has shifted to how the jihadists may regroup by working with its often shadowy affiliates elsewhere. It has already shown its capacity to operate in far-flung places while recruiting fighters in areas marked by political and social neglect.

With little access to electricity, let alone government jobs, many Bedouin tribesmen still seek a living through smuggling, and these illicit networks have dovetailed with a festering insurgency. In 2015, the Islamic State’s Sinai branch took credit for downing a Russian passenger jet full of tourists leaving the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh, killing all 224 people on board. Over the past year, militants have repeatedly fired rockets from Sinai into Israeli territory. All the while, hundreds of Egyptian soldiers have died, often in roadside ambushes or car bombings. A more aggressive Egyptian military crackdown, bolstered by Israeli assistance, including drone strikes, can’t seem to neutralize the threat.

Friday’s massacre underscores the challenge posed by the jihadists. “One thing that the group has been trying to do as it claims to be province [of the Islamic State] is attempting to take — or at least show — some kind of expanding authority,” said Zak Gold of the Atlantic Council to The Washington Post. “This attack doesn’t necessarily show that Islamic State has the authority over the area, but that the Egyptian state lacks authority.”

That, of course, is not the version of events you hear from Sissi or his lieutenants. Nor would it be welcome in the White House: Trump has repeatedly hailed Arab strongmen who mercilessly quash insurgents. But neither he nor Sissi seem to able to confront the seemingly obvious fact that terrorism can’t be eradicated by “brute force” alone.

Trump seems disinterested in the complicated political reconciliation and economic reconstruction that war-ravaged communities in the Middle East will need in the years to come. And Sissi’s government, according to reports, seems unwilling to contemplate a more sophisticated, velvet-gloved approach to dealing with Sinai’s insurgents.

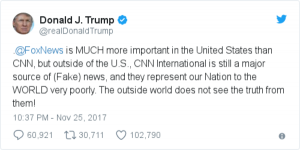

Instead, as Trump tweeted a bizarre attack on CNN’s international journalists over the weekend, the Egyptian foreign ministry followed with its own angry hectoring, chastising a CNN story on Sinai that pointed out the lack of access reporters get to the region. Cairo, it seemed, was acting with Trump’s blessing.

What any of this achieves for those suffering and trapped in northern Sinai is far less clear.

“We had to bury them in mass graves. In every hole, we would bury 40 or 50,” Muhamed Khalil, a local resident who helped bury whole families together, told my colleagues. “People were silent, motionless, unable to grasp the reality of what had happened.”

The mosque targeted in the assault was Sufi — that is, belonging to a strain of Islam steeped in a tradition of mysticism that is loathed by today’s jihadists. In Pakistan, Sufi shrines and festivals have been the targets of numerous militant attacks in recent years. But there’s also a temptation to overstate the political significance of Sufism as an antithesis to extremist Islam, as Shadi Hamid of the Brookings Institution explains:

“To describe Sufis as ‘tolerant’ and ‘pluralistic’ may also be true, but doing so presupposes that non-Sufi Muslims aren’t tolerant or pluralistic. On the other hand, describing Sufis as heterodox, permissive, or otherwise less interested in ritual or Islamic law is misleading…

“The idea that Sufis are inherently non-violent or pacifist is similarly ahistorical. Some of the most famous Islamic rebellions were led by Sufis like Sudan’s Mohamed Ahmed, who declared himself Mahdi, or ‘the redeemer,’ and Abdelkader in Algeria… Some of this may have to do with the fact that someone had to lead rebellions against foreign invasions; Sufi orders were popular and enjoyed considerable legitimacy. If they didn’t take charge, who would? Still, this would only mean that the fundamental “peacefulness” of Sufis is mostly circumstantial and has little to do with opposing jihad, as such, or rejecting violence more generally. Today, in countries like Syria, some prominent Sufi sheikhs have been vocal defenders of state violence, with Ahmed Kuftaro, the grand mufti until his death in 2004, supporting the Baath regime. (Without doing so, he wouldn’t have remained grand mufti).

“These are far from mere semantic discussions. They inevitably shape the subtext of so many conversations around Islam and politics. Western governments are susceptible to exoticizing Sufis and elevating them as the better, peaceful Muslims. But to see one group of Muslims as better means seeing other Muslims as problems to be solved. Westerners, most of whom have heard of Rumi’s poetry, but have little idea who the Mahdi is, will, naturally, prefer this idea of pacifist, apparently apolitical Muslims, only to find out that most Muslims are just, well, Muslims.”

• Elsewhere on the subject of the Islamic State, my colleagues Joby Warrick and Souad Mekhennet have a disturbing read on another dimension of the jihadists’ continued threat — the influence of its female adherents. From their story:

“In recent months, women immigrants to the Islamic State have been fleeing the caliphate by the hundreds, eventually returning to their native countries or finding sanctuary in detention centers or refugee camps along the way. Some are mothers with young children who say they were pressured into traveling to Iraq or Syria to be with their husbands. But a disturbing number appear to have embraced the group’s ideology and remain committed to its goals, according to interviews with former residents of the caliphate as well as intelligence officials and analysts who are closely tracking the returnees.

“From North Africa to Western Europe, the new arrivals are presenting an unexpected challenge to law enforcement officials, who were bracing for an influx of male returnees but instead have found themselves deciding the fate of scores of women and children. Few of the females fought in battle, yet governments are beginning to regard all as potential threats, both in the near term and well into the future. Indeed, as the loss of the caliphate has appeared ever more certain, Islamic State leaders in recent weeks have issued explicit directions to women returnees to prepare for new missions, from carrying out suicide attacks to training offspring to become future terrorists.”

• The New York Times ran an important investigation into the gutting of the State Department under Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who has presided over an exodus of career diplomats as well as the sidelining of a number of civil servants from minority backgrounds.

• Pope Francis arrives in Burma on Monday, on a visit fraught with the prospect of tension should the pontiff raise the issue of the Burmese military’s mistreatment of Rohingya Muslims and other minorities. A report in the Guardian indicates some Burmese Christians are wary of a nationalist backlash if the pope is too critical.