Aristeidis Voulgaris

Aristeidis Voulgaris

Head of the team

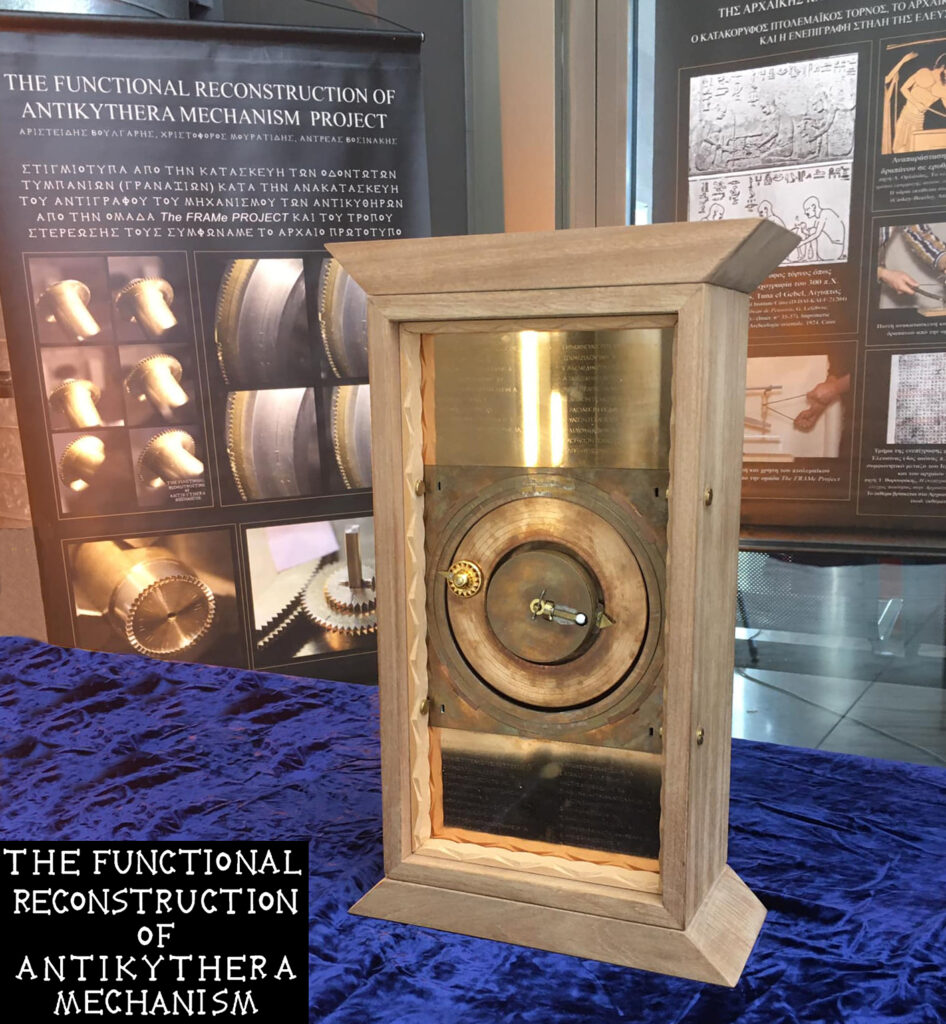

The Functional Reconstruction of the Antikythera Mechanism (FRAMe Project)

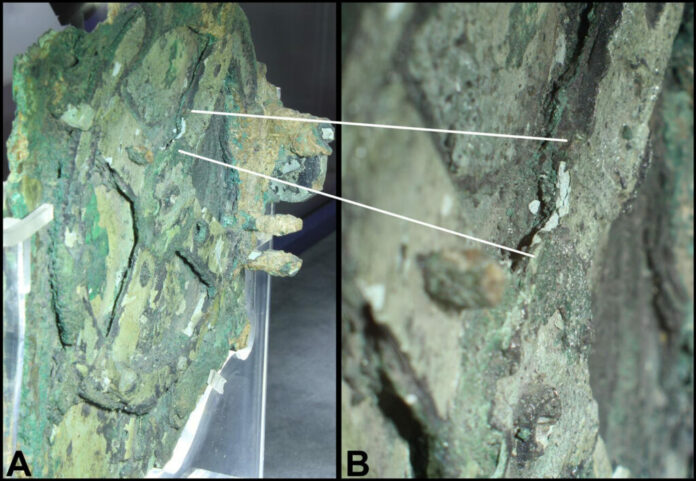

Photograph:

Left: Image of the central area of Fragment A showing gear b1 with its four spokes. Right: snapshot of the random break on part of one spoke. No trace of bronze survives inside the spoke, having been replaced by Atacamite (Voulgaris et al., 2022).

Responses and Clarifications

to reports in both international and domestic media claiming that “according to Argentine researchers, the Antikythera Mechanism was a non-functional toy of the Hellenistic period.”

(Note: The researchers’ work is stored in a manuscript repository and has not been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.)

The Antikythera Mechanism was constructed from bronze (an alloy of approximately 94% copper and 6% tin) around 150–180 BC. The cargo ship (a merchant vessel or olkas) transporting it sank off the coast of Antikythera around 86 BC.

Upon contact between the bronze and seawater, chemical reactions began immediately between the copper and the chlorine present in abundance in the sea, primarily as sodium chloride (common salt).

During its stay on the seabed for approximately 2,000 years, all bronze components of the Mechanism—gears, axles, pointers, and plates—were transformed into a new material known as Atacamite (copper trioxochloride).

Atacamite is a rocky-mineral substance with a density of 3.8 g/cm³, in contrast to the original bronze density of 8.8 g/cm³.

In 1901, the Mechanism was retrieved from the seabed, but the sudden dehydration it underwent caused significant shrinkage, deformation, and fracturing of its parts.

Today, the Mechanism survives in large and smaller fragments, irregularly deformed and shrunken in all three dimensions—resembling the state of a “mummy.”

Any dimensional measurement of the fragments—no matter how precise—is affected by the shrinkage and deformation resulting from material transformation and dehydration.

As a consequence, conclusions such as the claim that the Mechanism was a non-functional decorative toy, i.e., a “failed construction,” are at the very least misguided and incorrect. They do not reflect Reality, nor are they consistent with the exceptionally high level of design and craftsmanship of this unique artifact of the ancient world, which stands as a Global Monument of Antiquity.

In my opinion, as a researcher and builder of three functional models of the Antikythera Mechanism, this completely unfounded conclusion does a disservice to the talent and mechanical ingenuity of the ancient Maker—whose name, unfortunately, has not been preserved.

This Maker crafted the gears, axles, spindles, measuring scales with their pointers, and then went on to write the User Manual for his creation (which survives only in part—fragmentary sentences, words, and letters).

If any gear had developed a mechanical problem, he would have simply replaced it with a new one.

At that time, bronze was an exceptionally expensive material.

The manufacturing of the components was particularly difficult, labor-intensive, and time-consuming. There are gears with 229, 223, 188, or 127 teeth—constructing them remains highly demanding even by today’s standards.

The ancient Maker also constructed a ring with 365 holes, each approximately 0.8 millimeters in diameter. A misalignment of just 0.3 degrees would have ruined the previous or the next hole. (Try counting from 1 to 365…)

What would be the purpose of creating a device that was:

- so expensive,

- so complex,

- so time-consuming and painstaking to build,

- with an extraordinarily large number of components and holes,

- and accompanied by a User Manual—

if it were merely a non-functional toy?

The study of corrosion and geometric deformation of the fragments has been published in the following peer-reviewed papers by the team The Functional Reconstruction of the Antikythera Mechanism – The FRAMe Project, authored by Aristeidis Voulgaris, Dr. Christoforos Mouratidis, and Andreas Vossinakis:

- Voulgaris A., Mouratidis C., Vossinakis A. (2019):

Simulation and Analysis of Natural Seawater Chemical Reactions on the Antikythera Mechanism,

Journal of Coastal Research, 35(5), 959–972.

https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-18-00097.1 - Voulgaris A., Mouratidis C., Vossinakis A., Bokovos G. (2021):

Renumbering of the Antikythera Mechanism Saros cells, Resulting from the Saros Spiral Mechanical Apokatastasis,

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 21(2), 107–128.

https://www.maajournal.com/index.php/maa/article/view/529/460 - Voulgaris A., Mouratidis C., Vossinakis A. (2025):

Reconstructing the Antikythera Mechanism’s Central Front Dial parts – Division and Placement of the Zodiac Dial ring,

Journal of the Astronomical History and Heritage, 28(1), 257–279.

https://dds.sciengine.com/cfs/files/pdfs/view/1440-2807/B14DB9E8860042A1AF8B2997E4F33D33.pdf

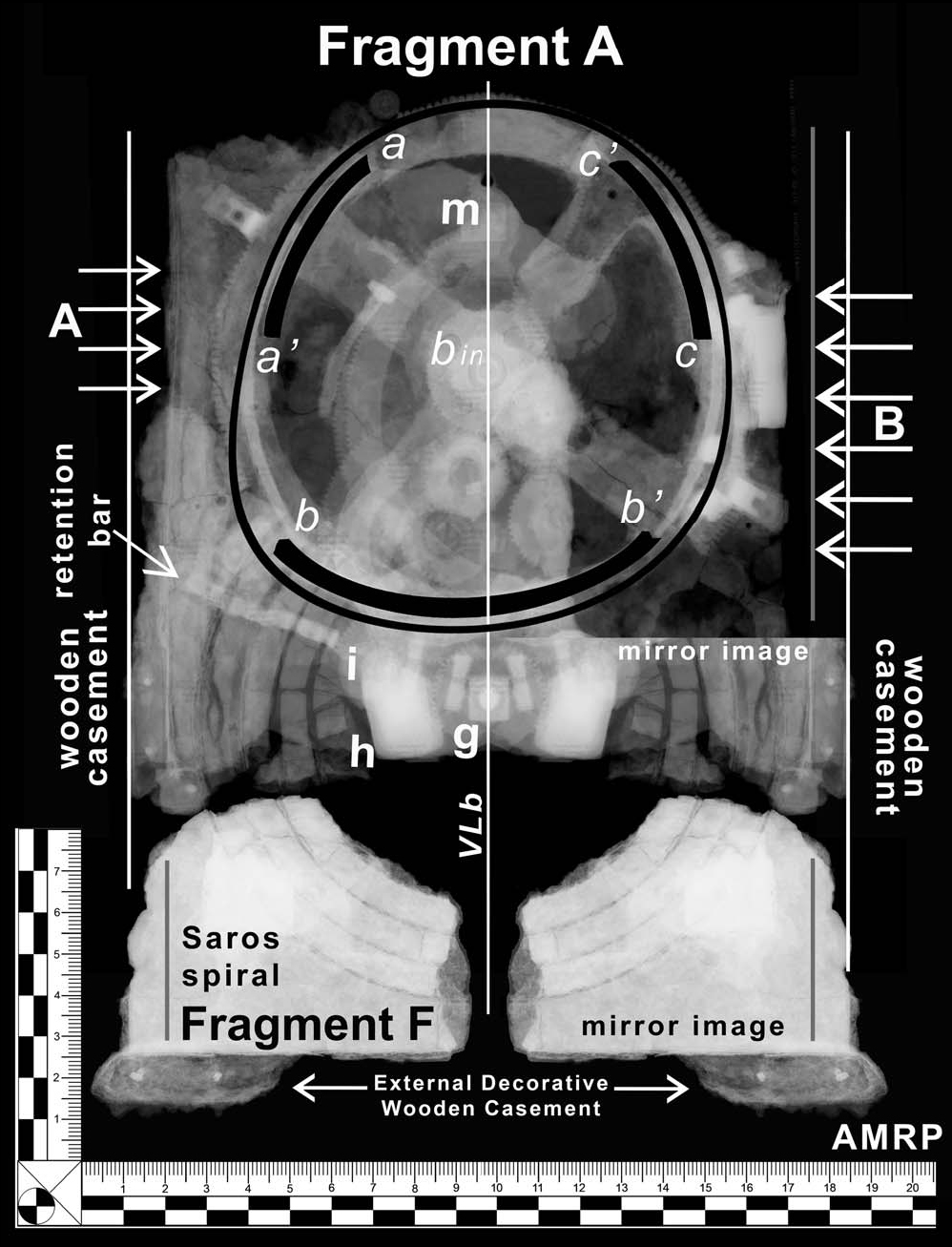

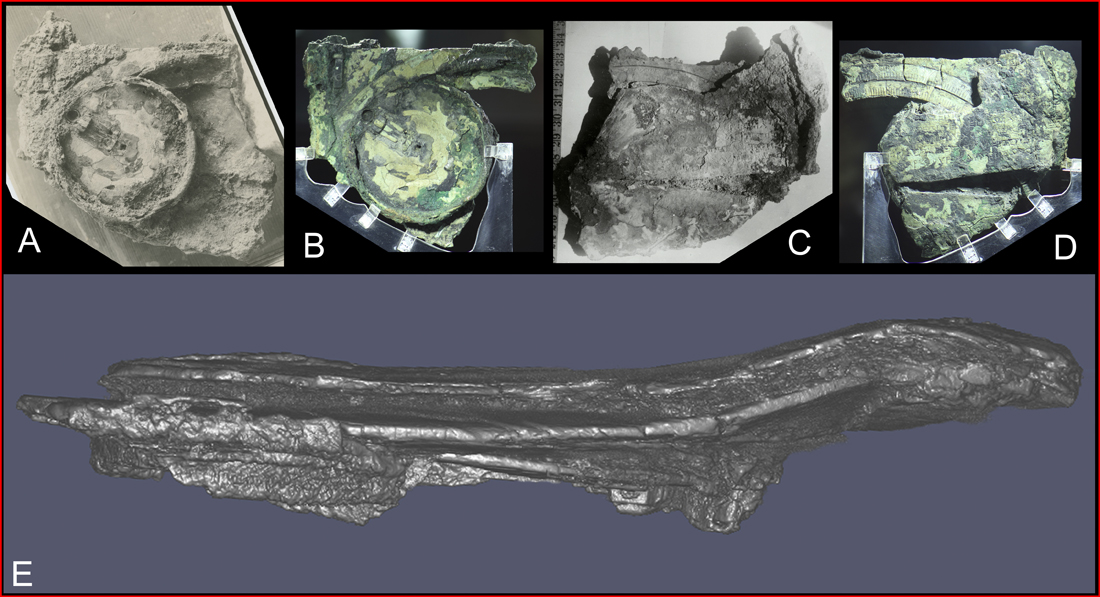

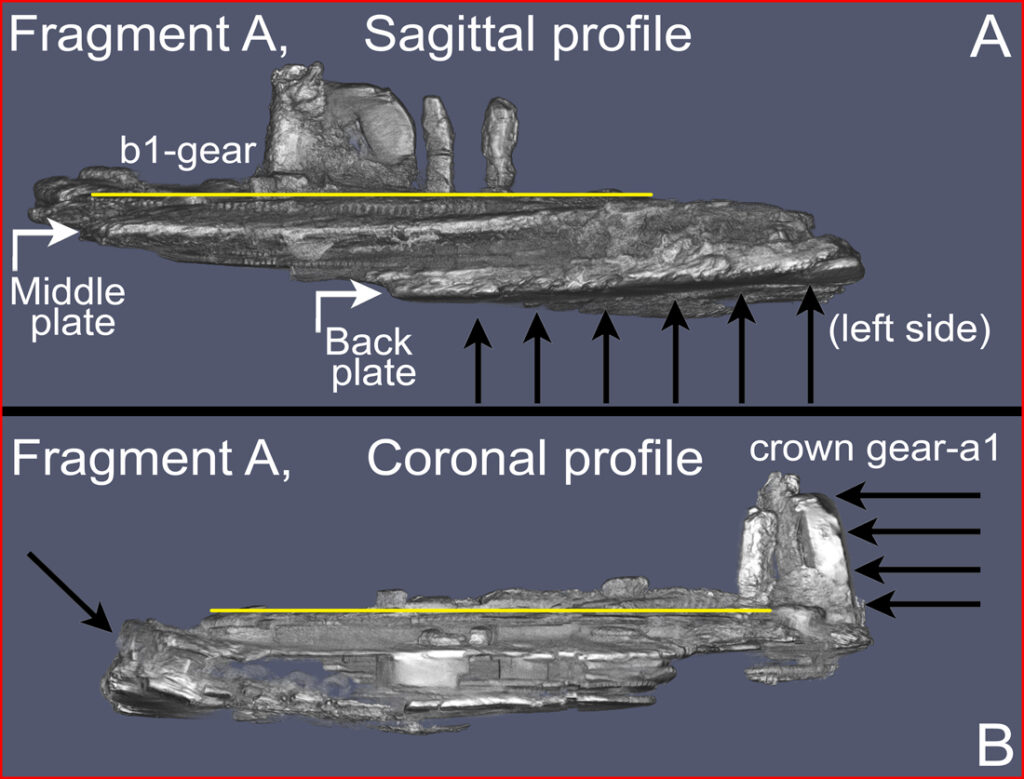

Presented below are representative photographs and CT scans of the two largest fragments of the Antikythera Mechanism (Fragments A and C), where deformation is clearly visible, as well as one of the functional reconstructions of the Mechanism developed by the team of The FRAMe Project.

Aristeidis Voulgaris

The FRAMe Project

Note: “The text by Mr. Aristeidis Voulgaris was originally written in Greek. Its English translation was carried out by Anixneuseis.”