The journey that led Fitim Lladrovci to become one of the most notorious men in the Balkans began in October 2013, when he was 23 years old. He pocketed his life savings of $350, said goodbye to his wife and left Obilic, a grimy town in central Kosovo. In Pristina, the capital, he boarded a plane to Istanbul and then took a second flight to Hatay, a province in south-east Turkey. He was met at the airport by a large Arab man in a black tracksuit and sunglasses who drove him to a single-storey house stacked with bunk-beds, where Lladrovci was surprised to find six other ethnic Albanians. Two were men; two were women whose husbands had crossed into Syria months earlier; two were children, a boy of two and a girl of six months who cried continually.

The next day the Albanians were driven to the border and told to proceed on foot for several miles until they reached a line of buses. They boarded a white minibus, and were joined by a band of men from the Caucasus whose wild red beards made them appear, said Lladrovci, “like lions”. They bounced across a sandy, lunar landscape, driving deep into Syria. “The countryside seemed beautiful to me,” said Lladrovci. “But I was shaking the entire time. What stressed me most was the idea of falling into the hands of Assad.”

Lladrovci travelled hundreds of miles to fight Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president who, in the early days of the Arab spring in 2011, had suppressed street protests. Later Assad began to kill his opponents. Lladrovci had never completed school or managed to hold down a job. His sense of justice had been forged at a young age when, in the 1990s, ethnic Albanians had risen up against the Serbs and, with help from America, fought for an independent state. Kosovo, the country they built, was overwhelmingly Muslim. Lladrovci believed that his role in Syria was akin to that of the Americans in Kosovo: saving an oppressed people. He spits out Assad’s name, dismissing him as “a man who doesn’t know a thing about Islam”.

The new recruit spent his first three nights in Syria in a factory on the outskirts of Aleppo, a city that was then divided between government and rebel forces. After days of travelling Lladrovci was relieved to find the floors carpeted with sponge mattresses. He lay down in a corner near the only people whose language he could understand. In Europe, Albanians are scattered across Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Greece and Albania itself. In a war-ravaged city in Syria, they found themselves wedged head to toe. “The Arabs arranged us like sardines,” he said.

Lladrovci planned to join the al-Nusra Front, an affiliate of al-Qaeda established in 2012, which operated in a loose alliance with a number of other militias, both Islamist and non-Islamist. Like all recruits, he handed over his life savings. In return, he was promised a salary of $115 a month, a respectable wage in Kosovo.

The men were given a choice of spending three months training to become a sniper or member of the tank division, or doing a three-week course then joining a strike team of foot-soldiers who would cross Syria to occupy territory. Lladrovci chose the latter option. He wanted to see action as quickly as possible. He spent his mornings at the shooting range, rattling off live bullets from his Kalashnikov, sprinting and shooting again. The rest of the day was taken up with prayers and lectures on religion.

Lladrovci says he went to Syria to save innocent civilians from slaughter. But he soon found himself caught up in a larger struggle about the future of Islam. Theological questions were contested on the battlefield. Was it acceptable to kill fellow believers in the name of Allah? Can one build a state from the blueprint of the Koran? Lladrovci grew convinced that only one organisation had the right answers: along with most of the Albanian recruits, he denounced al-Nusra and swore allegiance to Islamic State (IS) instead.

Lladrovci couldn’t understand Arabic and had only a frail grasp of the theological niceties that divided Sunni from Shia. But he found the ambition and fervour of IS simple and attractive: if you were not with IS, there was a target on your back. The group had perfected a made-for-screen ruthlessness – prisoners in cages, captives set on fire, death to anyone who stood in its way. Initially Lladrovci blenched at it. But, in the turmoil of uncertain alliances and in-fighting, he found IS’s clarity appealing. Civilians who were slaughtered by IS “got what was coming to them”.

Lladrovci spent a year on the battlefield in Syria before returning to Kosovo. He was imprisoned for three years – technically for hate speech, not for his activities with IS – then went back to Obilic. His only regret, he says, is having left Syria in the first place. “I would return tomorrow if I could,” he says. A higher share of Kosovo’s population has travelled to Syria to join IS than that of any other country. Between 2014 and 2016, more than 300 made the journey to Syria from one of Europe’s poorest states, according to the New York Times.

Today, IS does not exist as a geographical entity. But in Kosovo, the country that Lladrovci openly derides, he still proclaims his fidelity to the caliphate. He is just one among tens of thousands of people who left their homes to join Islamic State. These individuals represent a particularly intractable and rapidly growing problem for governments across the world. What should be done with the fighters who return?

In October 2018, a few months after Lladrovci was released from prison, I went to Obilic, a smoggy town of 6,000 people downwind of a hulking coal plant. When I asked my taxi driver about locals who left to wage jihad, he cursed Lladrovci as a “diseased dog”. “I lost half my family in the war against the Serbs,” he said. “You can’t find anyone in this country who didn’t lose someone. But you didn’t see us going to Syria to cut off heads.”

Lladrovci lives at the end of a muddy lane a few hundred yards from the power plant, in a cobbled-together structure of bricks and tarpaulin. A brood of chickens stalks the weed-strewn plot outside. I found Lladrovci bent over a wheelbarrow. When he learned why I was there, he told me never to visit him there again. He didn’t want to attract the attention of his neighbours.

Lladrovci is tall and sinewy. His skin has a grey tint. His long nose droops towards a thin goatee on his chin. He was unremittingly monosyllabic. Only his eyes showed any emotion, two dark orbs that flitted testily about their sockets and rarely met my own.

He was neither intimidating nor imposing. Rather, he seemed haunted by his experiences. Over the course of half a year, I met Lladrovci four times and talked to him for nearly ten hours. Sometimes his anger came on in sudden fits: “I feel a need to knife you,” he once said. At other times, his rage dispersed. He showed interest in my fixer’s sick mother, asking each time we met how she was feeling. But he remained mistrustful and evasive. When I asked to meet his wife, he curtly refused. Whenever our conversation strayed onto potentially shocking topics, he would pause and let off a sickly chuckle. “How many people did you kill?” Chuckle. “Do you currently possess a weapon?” Chuckle.

He spends most of the day at home and works at night as a security guard in the emergency ward of a hospital in Pristina, 10km to the south. The government has banned Lladrovci from attending the local mosque. On my first visit, other residents of Obilic, caught between contempt and fear, did their best to uphold the fiction that Lladrovci never came back (the taxi driver was an exception).

Lladrovci saw himself as an outcast long before he left for Syria. In 1998, at the beginning of the Kosovo war, his hometown of Drenica, in the centre of the country, was a hotbed of Albanian separatism. One of his earliest memories is of the bark of Serb paramilitaries who invaded the town, rounded up the adult men and shot dozens of them outside his elementary school. His elder brother Mentor tried to hide. But when the Serbs searched their home, they seized Mentor and bayoneted him in the head. They hung his unconscious body from the front door and pummelled it with rifle butts as Lladrovci watched. Mentor has never walked since. In an exodus of hundreds of people, the family fled south. They travelled by night through forests and crossed a river so cold, says Lladrovci, that “I have never stopped feeling it in my bones.” In Obilic, the family stopped running and started a new life.

Growing up, Lladrovci’s sense of himself as an internal refugee hardened into a permanent feeling of estrangement. To the diplomats and NGO workers who flooded into Pristina after the war, Europe’s youngest country appeared to be a land of opportunity. The capital was decked out in new ministries, shopping malls and an 11ft bronze statue of Bill Clinton, saviour of the Kosovars. But in Obilic, nothing changed. People eked out a living. The houses stayed shabby. The town and its environs have the worst rates of cancer in Kosovo, possibly because of factory fumes. Lladrovci says his mother was often sick; his brother couldn’t work. At the age of 12, Lladrovci became the family’s main provider. He did odd construction jobs and his friends say he sometimes shoplifted food. “Obilic was supposed to save us,” he says. “But it was instead hell.”

In the early 2000s, Wahhabism, a puritanical strain of Islam promoted by Saudi Arabia, seized hold of Kosovo. Money from the Gulf flooded in, funding gleaming new mosques with copper roofs and chrome fittings that bristled incongruously against squalid mountain villages. Imams were sent from the Middle East to supervise the new places of worship.

In the town of Skenderaj, near Obilic, a charity that provided aid for war orphans installed a conservative preacher. The municipality soon became a breeding ground for radical ideas. Skenderaj was one of the first Kosovar towns where girls en masse started wearing the headscarf. Among these was a 17-year-old called Mihane Baleci. In 2010 her cousin met Lladrovci and introduced the pair. Within three months, Baleci and Lladrovci were married.

At the time Lladrovci knew almost nothing about Islam. His new wife introduced him to radical clerics on YouTube. In the messy aftermath of the war in Iraq, many such preachers constructed a revisionist interpretation of America’s role in Kosovo’s wars, arguing that the Americans had turned the country into its vassal, rather than saved it. They claimed that sharia law would resolve Kosovo’s lawlessness and bureaucratic dysfunction. Far from being independent, they said, Kosovar Muslims had been sapped of their historical destiny.

By 2012, Lladrovci had begun to discuss these ideas in online chat-rooms with names such as al-Sharia and al-Jihad. The forums seemed to offer an escape from everyday life and a sense of direction. The brothers, as Lladrovci called the people who lurked on these message boards, had little in common beyond their age (most were in their early 20s). Many were poor; a few were comfortably off. Some had already been to Syria; others couldn’t find the country on a map. They seemed to comprehend Lladrovci’s anguish and purposelessness. And they offered a solution to his plight: the Koran.

The brothers also met in person – outdoors in a leafy corner of a park in Pristina. It was at one of these meetings that Lladrovci’s new life began. He had taken the bus from Obilic, having told only his wife where he was going. The brothers arranged themselves unobtrusively in a circle. In the course of at least a dozen sessions, the group debated topics of religious significance drawing on half-remembered teachings snatched from online sermons. But it was Syria that consumed most of their discussion. The conflict sparked profound questions. What would a state in the image of Allah look like? Why had the West come to Kosovo and Iraq but not to Syria?

For months, Lladrovci lived a second life. By the summer of 2013, five of the group had left in search of answers. The videos they sent from Syria showed them grabbing the world by the throat. They carried machine- guns and ordered around compliant people in a distant land. In October 2013, Lladrovci told his wife that he was heading to Syria to build a better life for them both.

Lladrovci is cryptic about who organised his journey to the Middle East: he talks about an Albanian man with a son called Mohammed who lives in Switzerland. The head of Kosovo’s counter-terrorist services, Fatos Makolli, has spent six years reconstructing the networks that funnelled Kosovars to Syria and Iraq. According to him, firebrand imams stoked fervour for jihad. A series of cells with links to al-Qaeda operated in parallel to them. These often received funding from Saudi Arabia. Recruiters within these cells picked off the angriest men, whom they thought would obey orders. “It was clear they were interested not in devout Muslims, but impressionable ones,” Makolli told me. Many of these men said to their parents that they were going to Germany to look for work. Instead, they bought plane tickets for Turkey.

At the Syrian end, the Kosovars found themselves under the command of Lavdrim Muhaxheri, known as the Emir of the Albanians. A former contractor with the American forces in Afghanistan, Muhaxheri was a bulky man who exuded authority. Lladrovci described him as a “man who knew how to command other men”. He organised his troops like a mafia but did little fighting himself, spending much of his time running a protection racket near Aleppo and locking up anyone who questioned him.

Muhaxheri’s own contradictory biography – an instrument of American power turned jihadist – embodied the twisted identity politics of the nascent Islamic State. Muhaxheri unified Albanian speakers from across the Balkans under his command. Week after week, they ate, slept, fought and prayed together. But Lladrovci despised their shared ethnicity. “For our entire lives we were made to take pride in this thing,” he said of his Albanian identity. He talked scornfully of Kosovo as a “land of misbelievers”.

There is a propaganda video called “The Clanging of Swords” that shows a group of Balkan fighters outside Aleppo. They brandish swords and black flags. The camera cuts to a pile of passports, which are set alight. “These passports are your tyrants,” intones Muhaxheri into the microphone, as their national identities – Albanian, Macedonian, Kosovar, Montenegran, Bosnian – go up in flames. “We are Muslims! The caliphate is your state now!”

Like many European fighters, Lladrovci was granted leave from Syria for one reason only: to fetch his wife. Baleci had always wanted to join Lladrovci. In January 2014 Lladrovci made his way back to Obilic, where he remained for several weeks. Makolli, hearing of Lladrovci’s return, dispatched agents to interrogate him. “We know you’ve been in Syria,” one said to him. A grenade launcher was discovered in his house. “It was an old Yugoslav weapon I got even before Syria,” Lladrovci protests. He was briefly detained and released on bail, but he didn’t show up for his court hearing two days later. By then he was back in Syria with his wife. “Fitim Ladrovci should never have been released,” says Makolli, who blames Kosovo’s dysfunctional bureaucracy for hindering his counter-terrorism efforts.

Baleci stayed in Manbij, a city in northern Syria that served as a dormitory town for Albanian women whose husbands were fighting at the front. In late May 2014, Lladrovci’s unit was ordered to help take Deir ez-Zor, an oil-rich province on the border between Syria and Iraq. Its capture would unify IS-held territory in the two countries.

On a napkin, Lladrovci sketched out for me the plan of attack on Abu Hamam, a dusty concrete town on the east bank of the Euphrates. The town’s inhabitants, tribesmen called the al-Shaitat, had been reinforced by Iranian paramilitaries. Lladrovci’s company was part of a three-pronged attack.

Lladrovci headed towards the border in a fleet of jeeps and pick-ups. Ragged groups of displaced people stood in awe as the convoy passed. Abu Hamam was eerily quiet when the Albanians arrived, apart from a few stray dogs, which they soon shot. The town had changed hands multiple times during the war and burned-out cars lined the pavements. But as the Albanians advanced, they were met with a hail of sniper bullets. They spread out in small squadrons, moving house to house to flush out the defenders. As Lladrovci’s team was entering one of these houses, two men on motorcycles opened fire on them with machine-guns. The Albanians rushed inside and took refuge in a brick oven on the second floor. Their radio had run out of battery so they couldn’t call for help. For hours, they lay pinned to the floor, shouting for their comrades to no avail. “It was the only time in the war when I felt that I was finished,” Lladrovci says. Only later did he learn that the other squadrons had been killed or routed.

Frozen in a crouch inside the house, not daring to move, Lladrovci could see a flock of sheep shuffling through no-man’s-land. For a moment he imagined he was back in Obilic, a town filled with pottering sheep. The crack of a sniper’s bullet woke him from his reverie. The shot narrowly missed him but kicked up a fragment of brick that gashed his right hand. Lladrovci was bleeding so badly that he thought he might die. He volunteered to run back to the commanders on the outskirts of the town and plead with them to send a tank to draw the enemy’s fire. His friends tossed pillows onto the ground to cushion his landing. Lladrovci leapt out of a window and sprinted away, chased by rifle fire that whistled about him from all sides. He managed to convince his commanders to dispatch a tank and his fellow soldiers were rescued.

Abu Hamam was taken the next day and the remaining townspeople rounded up. Muhaxheri found a tribesman who, under coercion, admitted to killing two Albanians with a grenade launcher. He roped the captive to a telegraph pole and addressed a cameraman in pidgin Arabic: “This man killed two soldiers of the Islamic State with a rocket. Glory to Allah!” Then he retreated 50 yards, lowered a mortar and obliterated the captive. About a month later, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of IS, declared the creation of a caliphate.

When I asked Lladrovci what it felt like to banish people he could not understand from lands he knew little about, he corrected me. He was not banishing these people, he said. He was “liberating” them.

In August 2014 Kosoov TV aired an interview with a woman named Pranvera Zena, who said that her husband and eight-year-old son Erion had gone on a weekend trip and never returned. Subsequently, Zena received a text from her husband saying that he had joined IS and Erion was in Syria. Sobbing, Zena showed photos of Erion kneeling before IS’s black banner. Kosovo’s government, she said, had failed to help her. She pleaded for other Kosovars in IS to bring Erion home.

Around the same time Lladrovci had noticed a young Albanian boy living in a military camp near Raqqa, the capital of the caliphate. He’d learned that his father was fighting on the front-line in Iraq near Mosul. Lladrovci was concerned about him – he too had lost his home as a young child. A relationship formed between the hardened fighter and Erion, a “quiet and frightened” boy. In the early autumn, Lladrovci started taking Erion to internet cafés on his motorbike once a week so that the boy could talk to his mother over Skype. Soon, Lladrovci approached Erion’s uncle with a demand: in exchange for $11,000 and immunity from prosecution, he would repatriate Erion.

It’s possible that Lladrovci had simply grown weary of war. But there may have been a more acute reason for wanting to leave. Muhaxheri had grown increasingly maniacal, videoing himself executing soldiers accused of spying. Lladrovci may have even begun to compete with him for the loyalty of the Albanian recruits and been tortured for challenging his authority. When I ask Lladrovci about his relationship with Muhaxheri, he just cackles.

Erion offered Lladrovci a way out. The boy’s fate had become a cause célèbre in Kosovo and the government was under pressure to rescue him. The prime minister authorised a plan that would give Lladrovci immunity in exchange for the “humanitarian act” of bringing Erion back. The operation was dangerous: the authorities needed to co-ordinate with the Turkish government to extract Lladrovci, his wife and the boy from hostile territory. Lladrovci smuggled the three of them out of Syria, along roads choked with refugees, the “most miserable-looking people” that Lladrovci had ever seen. The trio headed to Gaziantep, a city in Turkey, where they waited “paranoid of everyone”. After five days, Kosovo’s security services lifted them from their hotel and put them on a commercial flight home. Two undercover air marshals sat beside them during the flight.

The terminal in Pristina was a scrum of police and reporters. As Erion emerged from the plane, his mother rushed towards him to hug him. While the flashing cameras concentrated on the happy reunion, the security services quietly spirited Lladrovci and his wife away.

Erion’s family say they don’t resent Lladrovci for blackmailing them. “We begged as many Albanians in Syria as we could to bring Erion back,” Suad Sadullahi, Erion’s cousin, told me. “We even asked Lavdrim Muhaxheri. Fitim [Lladrovci] was the only one who agreed.” Two weeks after Erion had been returned, Sadullahi travelled to Obilic to give Lladrovci the promised money. When they met, Sadullahi began to appreciate why Lladrovci had turned to jihad. “I walked into that house, took one look at that family – the unbelievable poverty of that family – and I remember thinking to myself: Fitim’s reasons for joining the Islamic State had nothing to do with Islam.”

Within days of Lladrovci’s defection, IS issued a call for his head. A group of IS sympathisers cornered him in the street and he had to brandish a pistol to disperse them. Six weeks after his return, he was woken up by his mother from an afternoon doze. Forty police officers had surrounded the house. They had come to take him to prison.

Lladrovci believes that Kosovo’s authorities reneged on the deal not to prosecute him. The security services tell a different story. No sooner had Lladrovci returned, says Makolli, than he began to flood Facebook with reminiscences of his time in IS, including videos of decapitations and panegyrics to the caliph. Lladrovci doesn’t deny this, but says that life back in Obilic was miserable. He missed the excitement and solidarity of Islamic State. Most of his friends had secured EU visas and left town in search of a better life. Those who remained feared him. IS wanted him dead. Lladrovci would never admit this, but it is possible that he deliberately engineered his own arrest. Prison was the safest place for him.

During his three years in jail, Lladrovci was approached by radicalised inmates who wished to serve the caliphate in Europe. He met conspirators involved in ultimately fruitless plots to poison Pristina’s water supply and ambush a visiting Israeli football team. He kept up with news from Syria and mourned as, one by one, every Albanian he knew was killed in air strikes. He also found out that his wife had given birth to their son.

He had a different sort of visitor, too. Individuals from foreign embassies questioned him about terrorist networks across Europe. Why were rifles from the Balkans used in the Bataclan massacre in Paris in November 2015? Why were Albanian jihadists crossing the Adriatic to meet with Italian mobsters? Manacled to a table and dressed in orange prison scrubs, Lladrovci responded outrageously. “My son will become an excellent suicide-bomber,” he told one diplomat. Yet, though he disputes it, Lladrovci is widely believed to be an informant for Kosovo’s security services. “How else was he let out after only three years?” one Kosovar official said.

Governments across the world face the problem of how best to deal with returning jihadists such as Lladrovci. Administrations in the Middle East do not have the resources to tend to them. Their home countries have taken different approaches. Albania has imprisoned only the recruiters. Sweden has prosecuted almost no one. America appears to repatriate ISfighters when there is sufficent evidence to indict them on arrival.

The fight against al-Qaeda is a natural point of comparison. Al-Qaeda members were generally young, educated men of Arab origin in their 20s. France, Germany and Spain crafted legal mechanisms that allowed anyone involved in planning an attack to be imprisoned. Legislation passed after 9/11 enabled plotters to be locked up for 15 years or more – long enough, so the thinking went, for them to return to society mellowed by middle age.

But IS is not al-Qaeda. At its height, IS had 40,000 fighters from 80 different countries. Unlike al-Qaeda operatives, they don’t conform to a type. Usually, there is no evidence to link them to specific plots against their home states. The sole ground on which most can be prosecuted is membership of a terrorist group. Yet this is hard to prove. “Unless you have these people committing atrocities on video, it becomes their word versus someone else’s,” says Peter Neumann, professor of security studies at King’s College London. In most European countries, this crime does not carry a lengthy sentence. Already more IS members have been let out of prison than al-Qaeda members – many are still young and angrier than when they went in. More than 400 people currently classified as “radical” by the French prison system will be released before the end of this year. “IS pulled all these people into the jihadist orbit,” says Neumann. “It has brutalised them, interconnected them, given them certain skills. In ten years, over the next generation even, this huge pool of people can be re-activated, whether by IS or some new jihadist international.”

There are broadly two theories for how to deal with jihadists who return. The first – de-radicalisation – focuses on challenging their worldview. Repentent radicals visit prisoners to convince them to renounce their beliefs. Once released, ex-convicts are given jobs to reintegrate them into society. The other strategy – disengagement – is premised on the assumption that belief systems may never change. Instead, it focuses on convincing men such as Lladrovci that their tactics are simply futile. Former IS members may be allowed to espouse extreme views. But by placing them under constant surveillance and clipping their ties to other extremists, disengagement schemes try to deny them the capacity to realise their intentions.

When I first met Lladrovci, he was a few weeks into the disengagement process. Undercover officers observed him round the clock and he had been prevented from speaking to his old contacts. Yet he gloated to me about being able to obtain weaponry and said he had ventured back into the chat-rooms where he had first encountered the brothers. And his wife had not been jailed, even after she confessed to writing to the leader of IS offering to act as a suicide-bomber in Kosovo.

Six months later, when I returned to Obilic, Lladrovci was very different. Strutting up to me he declared, “I’m not armed! Don’t worry!” He no longer had qualms about shaking my hand and didn’t object to cigarettes or background music. Even his eyes had lost most of their paranoia.

He still acted a little strangely. He had picked up the habit of trying to kill stray dogs with rocks. When he played football, he would sometimes encourage teammates to pass to him by whipping a handgun out from his waistband (his friends insist this was only a joke).

Some of the town’s other residents seemed to have warmed to him. Most people I spoke to wanted to leave Obilic. Lladrovci had gone to Syria to make something of himself, said one. He was seen as forgivably aspirational, much like those who had gone to western Europe in search of work, and admired for bringing Erion home. The community has rallied around him, watching out for government licence plates or unfamiliar men with beards. As we were walking down the main street, a car honked at Lladrovci. He pointed his index finger to the sky in a salute to IS. The driver reciprocated. Disengagement has turned him into a kind of celebrity and Lladrovci has warmed to the role. When I asked him again whether he had any regrets, he snarled, “The caliphate is not finished yet!”

The security services have struggled to understand the paradoxes of a man who finally seems at home even as he hankers to return to Syria. “Do I think his nostalgia for the Islamic State is genuine? No,” says Makolli. “But do I think Fitim [Lladrovci] is dangerous? Yes.” (Since our final meeting, Lladrovci has been placed under house arrest.)

On my last visit to Obilic, I call Lladrovci. Instead, it is his wife who picks up the phone. “I know who you are,” she says to me. “I know about your meetings with Fitim. And I swear that if you contact him one more time, by Allah you will never walk again.”•

MIDDLE EAST

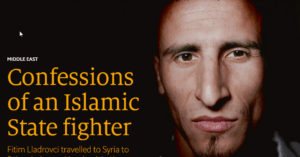

MIDDLE EAST Fitim Lladrovci travelled to Syria to fight a holy war. Now back in Kosovo, he continues to call for jihad. Alexander Clapp is granted a rare interview

Fitim Lladrovci travelled to Syria to fight a holy war. Now back in Kosovo, he continues to call for jihad. Alexander Clapp is granted a rare interview