By Michael T. Klare The Nation

By Michael T. Klare The Nation

Whether a Trump-dictated foreign policy is a good thing is anyone’s guess.

John Bolton, although considered an extremist by many for his staunch opposition to international agreements and fervent advocacy for the use of military force against perceived enemies, is nevertheless an unvarnished representative of the security-driven brand of politics that has dominated Republican policy-making since Ronald Reagan’s day. From this perspective, there still abides an “Evil Empire”—now under a Russian rather than a Soviet flag, but still governed by Moscow—and a constellation of anti-American states (Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela) that must be crushed, by any means necessary.

While serving as Trump’s security adviser and as director of the National Security Council (NSC), Bolton labored assiduously to promote these objectives. His first target was the nuclear deal with Iran, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Viewing the JCPOA as a boon to Iran’s clerical leadership, since it allowed that regime to remain in power—even if deprived of nuclear weapons—Bolton convinced Trump he could get a “better deal” by bringing Tehran to its knees through harsh economic sanctions. And when the Iranians failed to knuckle under but instead matched American taunts with provocations of their own—such as by shooting down an unarmed US drone over what they claimed was Iranian territory—Bolton advocated military action against Iran.

Bolton’s next target was the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty with Russia, a 1987 agreement that bans the possession of ground-launched missiles with a range of between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. This agreement, negotiated and signed by Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, was one of the last great achievements of Cold War détente but has come to be seen by Republican hard-liners as imposing a lamentable constraint on America’s ability to deploy missiles aimed at Russia’s and China’s critical military infrastructure. Bolton succeeded in winning Trump’s approval for a US withdrawal from the treaty, which became final in August.

Bolton’s traditional Republican views are also evident in his ongoing hostility toward Cuba and North Korea. For him and his conservative cohorts, the survival of those communist regimes represents unfinished business left over from the Cold War—and needs to be corrected as vigorously and expeditiously as possible. Hence the reversal of the Obama administration’s improved travel and economic ties with Cuba, and Bolton’s repeated threats to use force against North Korea if it continued its development of nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

But while Donald Trump went along with many of Bolton’s initiatives, he harbors a very different worldview than his former security adviser. Trump was never a member of the Republican Party’s foreign policy establishment; nor does he share its ingrained hostility toward Russia or readiness to employ military force. Rather, he has forged his own foreign policy outlook, one packed with grievances and priorities of its own.

To begin with the obvious, Trump seeks a world in which the Trump brand, the Trump Organization, and what’s now being called the Trump dynasty can flourish. This may seem trivial compared to other grand themes—“making the world safe for democracy” it’s not—but it’s probably foremost in the president’s mind. He clearly wants to be remembered as one of America’s greatest presidents, with giant statues and other monuments to his glory. He also seeks a global environment in which his progeny can build Trump towers virtually anywhere on the planet. This is not a world riven by perpetual military conflict, nor one made uninhabitable by thermonuclear devastation. Although Trump is unlikely to ever articulate a pacifistic message, his intense desire to promote the Trump brand abroad and ensure a legacy of personal greatness mitigates to some degree any inclination he may possess to engage in reckless military action against putative enemies.

In line with this outlook, Trump is open to grand bargains with erstwhile adversaries—if such agreements can be portrayed as burnishing his personal legacy of greatness. Yes, he characterized the JCPOA as a “bad deal” and pulled out of the INF because it was seen as unfairly advantaging Russia. But he is not opposed to deals with those countries, per se. If he can personally oversee an agreement that is seen as producing significant advantages for the United States, he’ll jump right on board.

There is, of course, another side to this coin: Trump prefers dealing with fellow autocrats who can join him in a private room with no one else but interpreters, and hammer out a deal. Trump’s affinity for foreign autocrats has long been noted, but will require further scrutiny in Bolton’s absence. Hard-line Republicans, with their abiding loyalty to Cold War precepts, continue to profess adherence to anti-communist shibboleths like freedom, liberty, and democracy. This naturally aligns them with the NATO countries against Russia, and with Japan and South Korea against China and North Korea. But Trump, for all his bluster, shares none of this; his core values are accumulating private wealth, promoting the Trump brand, ensuring the continued supremacy of white people, silencing detractors and journalists, and perpetuating the dominance of fossil fuels. Any foreign leaders who profess similar values are likely to be welcomed at the White House; those who don’t can expect a cold shoulder from Washington, whatever their historical ties to this country.

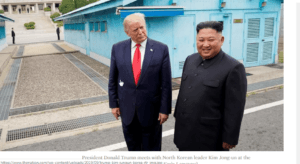

With Bolton gone, Trump is likely to reorganize the NSC staff in ways more to his liking. How this will play out in terms of specific issues cannot be foreseen, but it could ease the way for fresh talks with the Iranians and a new summit with Kim Jong-un of North Korea. Also possible is the convening of new arms control talks with the Russians, possibly increasing the odds for survival of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty when it is due to expire in February 2021.

At the same time, we should expect increased US support for right-wing strongmen like President Andrzej Duda of Poland and Prime Minister Viktor Mihály Orbán of Hungary. Accompanying this trend will be growing support for anti-immigrant measures worldwide, a retreat from advocacy for LGBTQ rights abroad, intensified attacks on international efforts to curb the consumption of fossil fuels, and the accelerated use of trade sanctions to punish insufficiently servile enemies and allies. Whether these developments, in the end, will outweigh any benefits that might arise from Bolton’s departure remains to be seen, but it should be clear that it will be Trump’s agenda that will dominate US foreign policy from now on, not that of his subordinate.