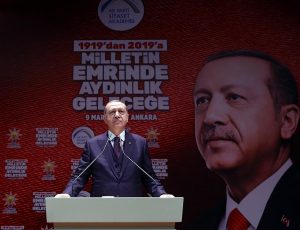

(Photo by Kayhan Ozer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Nate Schenkkan, Director for Special Research, Freedom House

The victory of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the June 2018 elections has cemented the long-term trend of democratic decline and authoritarian consolidation in Turkey. This consolidation has coincided with, and contributed to, a sharp divergence from Turkey’s traditional strategic alignment with the United States. This brief provides an overview of recent developments and looks at how U.S. foreign policy should respond to the “New Turkey.”

by Nate Schenkkan

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The victory of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the June elections has cemented the long-term trend of democratic decline and authoritarian consolidation in Turkey. Although the two-year state of emergency was lifted on July 19, the vast purge of the public sector, civil society, and the media that the state of emergency facilitated will not be reversed, and many of the most restrictive emergency measures are expected to be codified into law. President Erdoğan is already using his expansive new constitutional powers to restructure the state around his office.

This authoritarian consolidation has coincided with, and contributed to, a sharp divergence from Turkey’s traditional strategic alignment with the United States. This divergence seems to be premised on the assumption that Turkey needs to hedge against a collapsing regional or even international order. With the elections now completed, the United States should take this opportunity to reexamine its Turkey policy in its own right.

The US should maintain its goal of keeping Turkey in “the West,” and reevaluate its Syria policies with an eye to their consequences for the relationship with Turkey. But it must prepare for the possibility that Turkey under Erdoğan is pursuing a durable strategic realignment, in part by establishing a sliding scale of consequences that will fall into place if Ankara continues down its current path. The United States should draw redlines around its priorities: protecting US citizens, upholding the rule of law, and opposing a closer military relationship between Turkey and Russia. Washington has already begun to lay down these redlines through sanctions and other legislation. It should complement such efforts by investing in long-term support for Turkish civil society, independent journalism, and expert exchanges for Turkish citizens inside and outside the country.

The “New Turkey” is just beginning, and the United States should prepare to deal with it for the indefinite future.

INTRODUCTION

With victories in the simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections on June 24, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has consolidated his control over Turkey’s political system. Erdoğan will serve a five-year term, his first under a new superpresidential system that makes him head of state and head of government while he is also allowed to remain head of his party, and in which the parliament has been reduced to a semiconsultative role. Assuming he is still in good health, Erdoğan will be able to run for a second term in 2023, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Turkish republic and a symbolic date in Erdoğan’s self-created political mythology. For years, Erdoğan and the AKP have promised a “New Turkey,” a term that has taken on more sinister overtones as the president has directed a comprehensive purge of state institutions, civil society, and the media that began in 2014 but gained new momentum after the coup attempt of July 2016.

ELECTIONS OVERVIEW

The snap elections of June 24 were unusual in several ways. They were the first held within a new legal framework that features simultaneous parliamentary and presidential votes and encourages the formation of large multiparty blocs. Constitutional amendments passed in April 2017 to create a superpresidential system were set to come into force after the elections, lending the campaign a momentous air. Perhaps as a result, they were also the first elections of the Erdoğan era in which the opposition parties showed not just signs of life, but signs of a common effort to challenge the president’s power rather than clashing with one another.

However, despite the opposition’s relative energy and confidence going into the vote, Erdoğan won the presidency decisively in the first round, with 52.59 percent. What is more, the electoral coalition of the AKP and the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) won enough seats to easily constitute a majority in the 600-seat parliament, with the AKP taking 295 seats and the MHP 49. Even if the MHP decides to cooperate only on an ad hoc basis with the AKP, the ruling party is close enough to a majority that it will remain comfortably in control through tactical cooperation with other parties on specific issues.

The results have grim implications for democracy in Turkey. The country still has voting, but all other aspects of its democratic system are in shambles. The presidential candidate of the left-wing and Kurdish-oriented Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) ran from prison, where he has been held since November 2016 despite being a member of parliament and not being convicted of a crime. With the sale earlier this year of the Doğan media group to Demirören, a holding company that supports Erdoğan, the president has total control over a media sector that was already cowed by state interference. All of the state channels, and nearly all private broadcasters, heavily favored Erdoğan and his coalition in their campaign coverage. Opposition rallies faced a variety of obstructions, from roadblocks and electricity cuts to official bans and arrests, reflecting a hostile environment for freedoms of assembly and association. The fact that almost half of the country again voted against Erdoğan—even under these distorted conditions—indicates how contingent his hold on power really is.

Despite the pluralism of Turkish society, however, there is no longer a division of powers following these elections. There was some wishful thinking prior to the vote that an opposition-led parliament would be able to check some of Erdoğan’s consolidation. With the AKP-MHP coalition firmly in control, even that slim possibility is gone.

More importantly, Turkey is no longer a parliamentary republic. The constitutional amendments reduced the parliament to a semiconsultative body, stripped of the ability to form the government, hold a vote of no confidence, or even pose questions to ministers. As president, Erdoğan both names and heads the government without any parliamentary confirmation process, chairs the National Security Council, and issues decrees with the force of law. The parliament will follow the direction set by Erdoğan as head of the largest party, and the president will dominate the judiciary and the media even more than before.

THE NEW GOVERNMENT OF THE NEW TURKEY

The first weeks of the new system have revealed the extent of Erdoğan’s personal control. In appointing his cabinet, the president removed the last prominent technocrats—including Deputy Prime Minister Mehmet Şimşek—who had attempted to stem Erdoğan’s worst economic instincts and reassure investors. In Şimşek‘s place is Erdoğan’s son-in-law and former energy minister Berat Albayrak. While Albayrak has continued Şimşek’s policy of promising structural reforms, higher interest rates, and the independence of the central bank, these statements are hardly credible. Already, the Turkish lira and Turkish markets have resumed their preelection slide, suggesting that investors do not believe the government’s assurances.

Another notable change in the new cabinet is the direct subordination of the military to the president, as indicated by the appointment of the former chief of the military’s general staff, Hulusi Akar, as defense minister. Turkey’s military had already been largely brought under civilian control through a series of political trials beginning in the 2000s; since the coup attempt, Erdoğan has used the opportunity to purge its ranks again and promote his chosen officers. Akar, who was famously taken hostage during the coup attempt when he refused to cooperate, is the first active-duty military officer to serve as defense minister in Turkey’s modern history.

Even more important than the cabinet, the president’s first decrees over the last two weeks are a reminder that his executive pronouncements will give shape to the entire system of government. These decrees, consisting of hundreds of pages issued unilaterally by the president’s office, lay out in detail the roles and responsibilities of dozens of new government councils dependent on the presidency, give the president appointment powers for everything from high-ranking military officers to university rectors to the central bank president, and restructure basic state entities, for instance by placing the military’s General Staff under the Defense Ministry. Although the parliament’s lawmaking capacity is constitutionally superior to the president’s power to issue decrees, there is little chance that it will challenge Erdoğan’s overhaul of state functions.

THE STATE OF EMERGENCY IS DEAD, LONG LIVE THE STATE OF EMERGENCY

As promised during the campaign, on July 18 Erdoğan allowed the state of emergency that has been in force since the coup attempt to expire. The decision came only after a final round of purges, however. After the elections, another 18,601 public servants were fired by decree, bringing the total to at least 130,000 since 2016. In addition, according to monitoring by the Turkish Human Rights Joint Platform (İHOP), at least 80,000 people have been placed in pretrial detention as part of “antiterror” operations since October 2016. There are 178 journalists and media workers in prison. These dismissals and arrests—as well as the closure of over 1,400 associations and more than 175 media outlets, and the expropriation of nearly 1,000 businesses worth $11 billion—will not be altered by the expiration of the state of emergency.

Even with the state of emergency now lifted, there is little to prevent the president, with his working majority in the parliament, from taking the same sorts of actions. Erdoğan is already testing his new constitutional powers by restructuring the organs of the state, as discussed above.

In addition, new legislation being discussed by the parliament as of July 18 would put into law a number of the state of emergency’s features, including a three-year extension of the power to dismiss state personnel without adequate due process protections, further restrictions on freedom of assembly, and expanded powers allowing governors (who are appointed by Ankara) to control movement and residence in their territories.

THE ECONOMY

While Erdoğan is hastily putting in place the even more centralized state he promised, Turkey’s economy is reeling thanks to years of mismanagement at his behest. The government has long encouraged borrowing, including from foreign sources, to pump up national growth rates, which also had the effect of pouring money into the construction and real-estate sectors that Erdoğan favors. A downside to this pattern has been high inflation and a weakening lira, resulting in increased pressure to raise interest rates.

The president has consistently said that he thinks high interest rates cause high inflation, despite all evidence to the contrary. He has often commanded the central bank to keep interest rates low, but its slim measure of policy independence has allowed it to raise them at key moments, including before the elections when it looked like a run on the lira was building.

After years of stalling, Erdoğan is at a decision point: He can allow the central bank to do its job and continue to raise interest rates, which will cause a short-term but probably manageable slowdown, or he can insist that rates stay relatively low in order to bolster growth, which will push the reckoning further down the road but make it even worse when it comes. Whether they begin sooner or later, serious economic setbacks will play a major role in determining Turkey’s course in the coming years.

US-TURKEY RELATIONS IN TATTERS

The election outcome and the consolidation of a personalized, authoritarian system on its way to an economic meltdown is black news for US-Turkey relations, which have already been in a downward spiral for some six years. In a hoarse victory speech to supporters on election night, Erdoğan made a point of saying that the plotters of the 2016 coup attempt had fled to America, and that the votes from America had therefore backed the opposition. Given his victory, and the strong performance of nationalist parties that are skeptical toward the United States, it is hard to see Erdoğan abandoning the anti-American rhetoric he has leaned on so heavily over the last several years. However, the rhetoric is only a sign of deeper rifts.

Although President Barack Obama embraced Erdoğan as a model democratic Muslim leader early in his first term, the two hardly spoke during the second term. The split opened over Middle East policies following the Arab Spring, widened over Turkish treatment of protesters and journalists, and, since the coup attempt of July 2016, exploded over Turkish accusations of official US complicity and Ankara’s alignment with Russia on a number of strategic issues—especially through the planned purchase from Russia of the S-400 air defense system. A series of incidents in which Turkish presidential bodyguards attacked protesters in the United States, and Turkish prosecutors imprisoned American citizens and diplomatic employees in Turkey, drove the relationship to new lows.

After 2013, the Obama administration had largely given up on Erdoğan, attempting to change his behavior by freezing him out diplomatically. The policy approach principally sought to defer addressing problems in the relationship and to focus instead on destroying the Islamic State (IS) militant group in Syria in partnership with the local Kurdish-led People’s Protection Units (YPG), even as the spillover from that policy increasingly alienated Turkey, which regards the YPG as an organic part of the Turkey-based Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a terrorist group. The Obama administration arrived at its decision to cooperate with the YPG for logical reasons: IS was advancing rapidly across Syria and Iraq, and Turkey, which supported other Islamist rebel groups in Syria, had failed to show that any alternative force could confront the IS militants effectively. But the result was that from approximately mid-2014 through 2017, the United States’ Turkey policy was subordinate to its Syria policy.

Viewing the war in Syria through the narrow window of the fight against IS, and Turkey primarily as it was reflected in that window, caused the Obama administration to disregard deep changes in Turkish foreign policy. In the years since the Arab Spring, Turkey’s approach appears increasingly premised on the assumption of a collapsing regional or even global order. The failures of the revolutions in Libya and Egypt, the war in Syria, Russia’s occupation of Crimea, and the European Union’s institutional crises combined to form an image of a region sliding toward chaos. The 2015–16 wave of terrorist attacks in Turkey, and the coup attempt, solidified this pessimistic perspective.

The self-perception of Turkey as sheltering against anarchy is a mirror image of the optimistic worldview put forward by former AKP foreign minister and prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu during his years in office. Under Davutoğlu, Turkey proclaimed itself the rising force of the Middle East, Southeastern Europe, and even the Islamic world as a whole, arguing that it was perfectly positioned to act as a pivotal power for adjoining regions and for Muslim republics globally in a time of democratic and capitalist ascendance. In the dark outlook that has replaced Davutoğlu’s vision, Turkey is instead perched on the edge of chaos, surrounded by civil wars, hostile powers, and terrorist threats that demand revisionist solutions.

To this end, Turkey has occupied several border districts of northwestern Syria in order to stave off the YPG. It will remain an occupying power in Syria for the foreseeable future. It has reached a rapprochement with Russia and the Assad regime over this sphere of influence, restarted or refreshed two strategic energy projects with Russian cooperation, and agreed to purchase the S-400 air defense system despite increasingly blunt NATO and American warnings. It has pursued its perceived opponents outside its borders, including by conducting renditions from sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia, and Europe. Lastly, it has used various forms of diplomatic blackmail against its allies, including by threatening to send refugees to Europe and taking US and European citizens hostage as bargaining chips.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION AND CONGRESS

The US government has been seeking to put the relationship back on better footing, but there is little evidence that Turkey is eager to reciprocate. The decision on July 18 to continue to hold American pastor Andrew Brunson—which should be understood as political, just as the initial decision to imprison him was—indicates a lack of willingness to take even basic steps to restore normalcy to the relationship.

The Trump administration has stated its goal as keeping Turkey “pointed towards a Western future both politically and strategically,” as Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Eurasia A. Wess Mitchell said recently.

Politically, there seems little reason not to take Erdoğan at his word when he repeatedly claims to believe that the West is behind conspiracies to overthrow him, and then acts on those statements by imprisoning American citizens and foreign employees of American diplomatic missions in Turkey. The dismantling of the separation of powers has created a highly personalized and autocratic system that makes a deeper political alignment with the United States difficult to imagine. Strategically, Turkey lies along the frontier where NATO and Russian influence meet. In the framework the administration has articulated, the country must therefore play a substantial role in strategic thinking about the geopolitical threat from Russia.

Keeping Turkey in “the West” is a reasonable goal, but the question is, at what cost to the West? Given the deep changes in Turkish foreign policy over the last two years, it is not clear whether Ankara still regards NATO as the cornerstone of its security, or if it sees the alliance instead as part of a collapsing regional and international order. Is NATO the backbone of Turkey’s strategic posture, or is it a risk to be hedged against? Turkey’s value as a partner to the United States, and the cost-benefit analysis of investing in that partnership, depends on Ankara’s own approach toward the alliance.

There is an opportunity now for a long-overdue reexamination of the United States’ Turkey policy in its own right, rather than principally through the lens of Syria. As detailed above, decision-making about Syria and the war on IS have played an outsized role in policy decisions affecting the US-Turkey relationship. Turkey’s rejection of US operations in northern Syria must be taken into account in determining long-term US plans for its military operations in the Middle East. A US withdrawal from northern Syria and shift away from supporting the YPG would provide an opportunity to reset the parameters of the US-Turkey security relationship and defuse one of several major problems between the two countries. It is also the only policy shift toward the Turkish position available to the United States that does not infringe on core American values or interests.

Even if the US is able to make such a shift on Syria, Washington must continue to communicate to Turkey the consequences of pursuing an apparent strategic realignment through its purchase of the S-400, its imprisonment of American citizens and employees, and its authoritarian consolidation. More specifically, this communication should establish a sliding scale of consequences that will fall into place if Turkey continues down its current path..

The following elements of such an approach are already under way or available for use:

- As approved in a Senate measure in mid-June 2018, block Turkey from obtaining F-35 fighter jets if Ankara goes ahead with the purchase of the S-400 air defense system from Russia.

- Use the sanctions authority under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) (P.L.115-44), which would place Turkey under harsh secondary sanctions if it chooses to purchase the S-400 from the sanctioned Russian entity that provides the system. Assistant Secretary Mitchell confirmed in June that such consequences had been clearly communicated to Turkish officials.

- As proposed by senators on July 19, oblige the administration to oppose financing for Turkey from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) until the United States can confirm that Turkey is not arbitrarily detaining American citizens (including dual citizens) and local employees of the US mission to Turkey.

- Impose steep fines against state-owned HalkBank for its facilitation of sanctions-busting by Iranian entities. These fines are already the subject of protracted negotiations between the US government and HalkBank.

- Issue targeted sanctions against officials responsible for serious human rights violations, especially the unwarranted detention of American citizens and employees. These sanctions can be implemented through the Global Magnitsky Act (P.L.114-328), special legislation, or other means. While no individual sanctions have yet been imposed, the expected release of the next Global Magnitsky list in December 2018 will present another opportunity.

These policies could reinforce American redlines on the procurement of Russian weapons systems, Iran sanctions violations, the unwarranted detention of Americans, and the persecution of Turkish human rights defenders and journalists. They communicate in deed and not just in word to Turkish policymakers the consequences of a deeper realignment away from NATO—which is what Ankara’s current trajectory will achieve if it continues. However, these policies cannot and should not be expected to restore the strategic alliance if Turkey’s government does not want it.

With this in mind, the US needs to undertake a thorough reconsideration of its own strategic reliance on Turkey. While the prospect of Turkey crashing out of NATO still seems improbable—this is a country that remained a member even after occupying northern Cyprus—the US must be ready for all eventualities at a time when history seems to be moving at a faster pace. This should include reviewing and preparing options for the withdrawal of the US military presence at Incirlik airbase in southeastern Turkey. The executive branch may understandably be reluctant to engage in this conversation in public, but Congress should hold hearings on the US-Turkey relationship in order to focus attention on the potential impact of a deeper crisis in relations, and to identify additional actions that may be required.

Lastly, as the elections have shown again, there are huge constituencies in Turkey that oppose the direction in which Erdoğan is taking the country. While the diversity of these groups has made it hard for them to combine their efforts, and the repression they face has made it difficult to mobilize, they should not be abandoned. The US should use a variety of instruments to sustain contacts with and support Turkish citizens who want to see a return to the rule of law, tolerance, and protection of human rights. The executive branch should invest in exchanges, education programs, and outreach to the Turkish public; Congress should press for these kinds of projects. In addition, USAID should drop its long-standing policy of not conducting democracy and governance work that benefits Turkish citizens, and provide funding for journalism and civil society groups working in Turkey and in exile.

CONCLUSION

There will be many debates over the coming months about the New Turkey and its significance. The most important question for the United States is whether Turkey’s major foreign policy shifts over the last several years—to embrace cooperation with Russia on several issues, to occupy part of northern Syria, and to threaten its allies—represent a strategic change or tactical maneuvering. Turkey’s relations with the US and NATO have gone through decades of ups and downs; once tempers cool, this may prove to be yet another flare-up in a history filled with them. But especially at a time when geopolitical competition from Russia in the region is more overt and aggressive, the US must be open to the possibility that Erdoğan is realigning Turkey strategically, take measures to prevent that realignment, and prepare for even more substantial ruptures in the relationship in the future.

https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-reports/dealing-new-turkey-recommendations-us-policy-after-elections