By Ishaan Tharoor The Washington Post

By Ishaan Tharoor The Washington Post

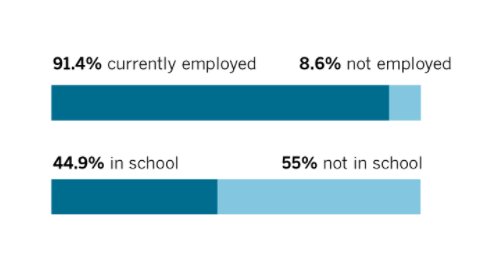

That line struck me in the wake of the Trump administration’s move to unwind an Obama-era program that gave legal rights and guarantees against deportation to nearly 800,000 undocumented people brought to the United States as children, often known — appropriately, for our purposes — as “dreamers.” These are people who know no real home other than the United States, who are productive members of the American workforce, sometimes serve in the U.S. military and abide by the nation’s laws.

As participants in Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, usually known as DACA, they entrusted their personal information to a government which may soon use that data to conduct mass arrests and deportations. Their fates — in many instances, those of their families — hang in the balance as the White House dangles red meat to its right-wing base. Dreams are turning into nightmares.

The Trump administration, led publicly in this effort by notoriously anti-immigrant Attorney General Jeff Sessions, argues that DACA takes jobs from American citizens and encouraged an influx of more child arrivals. Both these points, while parroted by far-right media, have little basis in fact.

Even from a cold, number-crunching perspective, ending DACA could cost the American economy anywhere from $280 billion to $433 billion over the next decade, setting employers back by $2 billion and the federal government by $60 billion. This is all aside from the moral argument against shattering the lives of close to a million people who see themselves as Americans, an act that former president Barack Obama called both “cruel” and “self-defeating” in a rare public statement Tuesday.

Of course, the United States is far from the only place where the emotive allure of nativism can overshadow the complex realities of immigration. In Britain this week, the Guardian published leaked Home Office documents that detail the government’s tentative plans to revamp Britain’s immigration system in the wake of its eventual departure from the European Union. The leaked proposals read “like a prison governor’s report, less concerned with the inmates than with the height of the perimeter fence,” Guardian columnist Simon Jenkins wrote. It has set off a panic among myriad European nationals living in Britain, who are alarmed by the severity of the proposed restrictions on their ability to remain and work in a country many consider home.

Questions over immigration and refugees have polarized Western politics for years, fueling the rise of far-right parties that built their movements on fear of foreigners and anger at the political establishments that let them in. These concerns have supplanted the more complicated challenge of reckoning with widening income inequality, which is largely not driven by demographic change. And, often, the fears of immigrants are overblown.

In Britain, for example, an Ipsos Mori survey conducted in 2016 found that voters thought, on average, that 15 percent of the population were E.U. nationals from outside the United Kingdom. Official figures at the time put the number closer to 5 percent, and later analysis has suggested the number may have been even smaller. A similar 2015 poll of supporters of the main party calling for Brexit found that they overestimated Britain’s immigration population by 100 percent. And a 2016 poll, conducted in the shadow of the U.S. election campaign, found that Americans thought the overall share of the Muslim population was 17 times its actual size.

These distorted views, sometimes stoked by sensationalist media and the echo chambers in which increasingly fragmented societies exist, are rather acute when it comes to refugees. A Pew survey this year, for example, measured what people with different ideologies considered major threats: “In all of the countries surveyed in Europe and North America, those on the political right are more concerned about the large number of refugees coming from the Middle East than those on the left,” Pew noted. “For example, in Germany, 51 percent on the right say that the movement of refugees is a major threat, versus only 14 percent who say this on the political left. A similar divide exists in the U.S. between self-described conservatives (60 percent say refugees are a major threat) and liberals (14 percent).”

A protester holds a poster, showing German Chancellor Angela Merkel wearing a hijab, by anti-immigrant group PEGIDA in Dresden, Germany in 2015. (Jens Meyer/Associated Press)

On the political right, many seem to belong to a ‘republic of fear.’

“People in general tend to believe that things that they don’t like or are anxious about are more extensive than they actually are,” Rogers Smith, a political-science professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said last month to my colleague Catherine Rampell. “They think the crime rate is higher than it actually is, that we give more to foreign aid than we really do by a large margin.”

And, as my colleague Aaron Blake reported Wednesday, other new polling from NBC News and the Wall Street Journal shows that the ultranationalist pillars upon which Trump built his political platform are wobbling. Sixty-four percent of Americans say that immigration strengthens the United States, a marked rise from 41 percent in 2015. Pro-immigration sentiment is up 10 points among Republicans, to 44 percent, compared with seven years ago. And for the first time in 20 years of polling, a majority of Americans think that globalization — Trump’s great bugbear — is “good” rather than “bad.”

Such numbers provide some hope that once people see fear at work, they’ll be willing to turn away from the nightmare.